Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

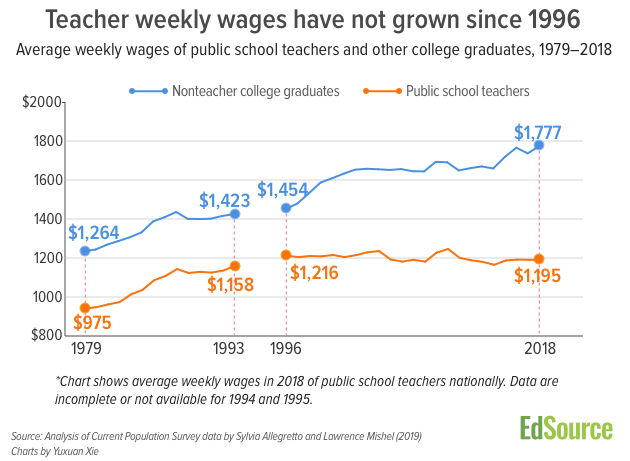

Teachers are continuing to fall behind other college graduates in the wages they earn, contributing to the difficulties many school districts in California and the nation face in filling positions in key subject areas, according to a new analysis.

The analysis is contained in a paper issued this month by Sylvia Allegretto, co-chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at UC Berkeley, and Lawrence Mishel, a distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive Washington D.C.-based think tank.

In 1979, teachers earned 7.3 percent less than other comparable college graduates — experiencing what the authors call a “wage penalty” — but by 2018 that gap had grown to a record 21.4 percent.

The implications of the wage gap for the success of the entire public education enterprise are far-reaching, the researchers wrote. “Improving public education — by preventing teacher turnover, strengthening retention of credentialed teachers and attracting young people to the teaching profession — requires eliminating the teacher weekly wage and compensation penalty”

On average, teachers nationally earned 78.6 cents on the dollar in 2018 compared to the earnings of other college graduates — and much less than the inflation adjusted 93.7 cents on the dollar that teachers earned in 1996.

In fact, in 2018 dollars, teachers’ weekly wages have not grown over the past two decades.

“There is a growing consensus that the United States faces an unprecedented shortage of teachers,” Allegretto said. “The teacher wage penalty is a large reason why. We must undo the teacher wage penalty and begin to pay teachers competitive salaries.”

The wage gap is exacerbating the difficulties teachers are having in covering basic expenses such as housing in high cost areas of the nation. That is most notably the case in coastal areas of California where only a small percentage of teachers are able to afford even modest rental housing, as documented by a recent EdSource special report.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said one reason salaries are so low “is because people have perceived the teaching profession as women’s work and they are paid less.”

“That is an injustice that needs to change,” he said. “We need to recognize that educators provide great, great support for our kids and we have to provide better compensation. There is just no other way to look at it.”

In 2018 the average teacher’s weekly wage was $1,182. That is 32.7 percent less than the $1,777 weekly wage earned by other comparable college graduates. That’s double the 16.4 percent wage disadvantage teachers experienced in 1996.

Despite tremendous changes in the workforce and the opening of numerous other opportunities for women, women still comprise three-quarters of all teachers. Allegretto and Mishel’s research provides a powerful explanation for why.

They found that the wage gap is especially large for male teachers — growing from 17.8 percent in 1979 to 31.5 percent in 2018 compared to other male college graduates. That, Allegretto and Mishel argue, “goes a long way toward explaining why the gender makeup of the profession has not changed much over the past few decades.”

In fact, the percentage of men teaching in public schools has dropped from 32.2 percent in 1979 to 24.9 percent in 2018, “a trend that is consistent with a male teacher wage penalty that is extraordinarily high and rising,” the authors state.

While what women teachers earn has improved over many decades, their wages still fall behind what other college graduates earn. And that has not always been the case for women in the teaching profession.

In fact, in 1960, women teachers earned 14 percent more in weekly wages than comparable women workers. But now women teachers are making 15 percent less in wages than comparable women workers.

Allegretto and Mishel point out that one positive side of teachers’ compensation is that the benefits they get make up a larger part of their overall compensation package than they do for other comparable college graduates.

This “benefits advantage” only partially offsets teachers’ lower wages. The authors say that the wages teachers receive are more important. “Only wages can be saved or spent on housing and food and other critical expenses,” they note.

There are also substantial differences in the wage gap among states. California teachers on average earn 16.3 percent less than other college graduates — making it the state with the 32nd-highest wage gap in the nation. Arizona, with a 32.6 percent wage gap, tops the list.

Allegretto and Mishel point out that four of the seven states where teachers earnings lag the most — Arizona, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Colorado — experienced major teacher strikes over the past few years.

“It’s no surprise that the states that have seen teachers strike and walk out over the past year are the states that have some of the highest teacher wage penalties,” Mishel said. “While teacher pay is only part of the story, it is an important element. If we are going to have excellent schools, we must make sure that teachers are paid for their work.”

Until the wage gap is closed, State Superintendent Thurmond said “creative strategies” will be needed to help teachers cope with the high cost of living in California. He has, for example, proposed providing districts grants to build affordable housing on surplus property for school personnel.

“If we are honest, California is a hard place to be a teacher,” he said. “Salaries are low compared with other industries, living conditions are hard and work conditions are hard. If we want to close our teacher shortage we have to do a better job at compensation.”

The overreliance on undersupported part-time faculty in the nation’s community colleges dates back to the 1970s during the era of neoliberal reform — the defunding of public education and the beginning of the corporatization of higher education in the United States. Decades of research show that the systemic overreliance on part-time faculty correlates closely with declining rates of student success. Furthermore, when faculty are… read more

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Comments (12)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Michele 5 years ago5 years ago

When you look at total compensation, including pensions and benefits, teachers are actually paid quite competitively with other professions. When you add in the number of work days (and holidays and time off), they actually make more then many professions. Yes, I am aware that teachers work beyond their "scheduled" 5 or 6 hour day, but most professionals do - many work 50 and 60 hour weeks regularly, and have no pensions and … Read More

When you look at total compensation, including pensions and benefits, teachers are actually paid quite competitively with other professions. When you add in the number of work days (and holidays and time off), they actually make more then many professions. Yes, I am aware that teachers work beyond their “scheduled” 5 or 6 hour day, but most professionals do – many work 50 and 60 hour weeks regularly, and have no pensions and very limited benefits. So this really isn’t a fair or realistic analysis.

ann 5 years ago5 years ago

Well, I was fairly certain this analysis was questionable if not fully inaccurate and went to the source where it was obvious this was a sham. I am very pleased to see others have taken the case. Still I am exceedingly bothered that it was published as though it had merit.

SD Parent 5 years ago5 years ago

My first thought when I read this article was "Where did they get the numbers, and how did they do the analysis?" because there isn't even a mention of the number of working days for teaching vs. other professions. I would refer everyone to Todd's analysis and the string below his analysis. He demonstrates conclusively that the often-popagated idea that teachers in California are underpaid relative to other college graduates is a narrative … Read More

My first thought when I read this article was “Where did they get the numbers, and how did they do the analysis?” because there isn’t even a mention of the number of working days for teaching vs. other professions. I would refer everyone to Todd’s analysis and the string below his analysis. He demonstrates conclusively that the often-popagated idea that teachers in California are underpaid relative to other college graduates is a narrative not based on fact.

I would add that some of the overall wage gap in California between college graduates is a result of the high salaries paid to those in technology fields (Google, Apple, etc.), an industry that didn’t exist 40 years ago. This is driving the housing crisis in the Bay Area and apparently this discussion of teacher salaries, which seems to be a regional issue. For example, I suspect the wage gap between teachers and other college graduates is higher in San Francisco than Fresno or Stockton.

As for other comments regarding benefits, San Diego Unified School District employees pay no part of their healthcare premiums (including for their spouses and dependents), just a $10 co-pay for a doctor’s visit or prescription, even for PPO plans.

Alvina Arutyunyan 5 years ago5 years ago

I agree with comments that these analyses are inadequate. We need to make sure that we don't pick facts to promote certain agenda. Shortage of teachers might more to do with other facts than wages – for example approval of credentialing, slow processing of approvals and other systematic issues. If we have a shortage of teachers, which we do, one of the ways is to increase wages but there are other areas we should look … Read More

I agree with comments that these analyses are inadequate. We need to make sure that we don’t pick facts to promote certain agenda. Shortage of teachers might more to do with other facts than wages – for example approval of credentialing, slow processing of approvals and other systematic issues. If we have a shortage of teachers, which we do, one of the ways is to increase wages but there are other areas we should look into based on unbiased comprehensive analysis.

Dan Plonsey 5 years ago5 years ago

The "benefits advantage" is only an advantage in comparison to other workers. Teachers have had enormous losses in benefits! A first-year teacher with a family in my district (Berkeley) would have paid $0 for health care 15 years ago. Now they pay 25 percent of their salary -- and my district contributes a larger amount than most. We also pay a larger amount for pension than a few years ago: 10% vs. 8%. But the … Read More

The “benefits advantage” is only an advantage in comparison to other workers. Teachers have had enormous losses in benefits! A first-year teacher with a family in my district (Berkeley) would have paid $0 for health care 15 years ago. Now they pay 25 percent of their salary — and my district contributes a larger amount than most. We also pay a larger amount for pension than a few years ago: 10% vs. 8%. But the idea of building housing does not seem a good solution: then teachers will have an even harder time leaving districts, and thus have even less bargaining power.

And besides, although teachers are paid poorly, so are many others. We need a more general solution to the problem. It seems to me that as long as our economic system prioritizes profits, income inequality can only grow, and we will be unable to address the problems of health care affordability, and for that matter, find solutions to climate change.

Todd Maddison 5 years ago5 years ago

This is a rehash of an article posted a few weeks ago, using the same suspect numbers. The EPI's numbers are questionable. I can't speak to the rest of the country, but I've done an analysis of their California numbers, and they're just plain wrong - based on verifiable, reliable sources (like the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the US Census Bureau, the California Department of Education, etc...) I don't know where the 2019 numbers came from, … Read More

This is a rehash of an article posted a few weeks ago, using the same suspect numbers.

The EPI’s numbers are questionable. I can’t speak to the rest of the country, but I’ve done an analysis of their California numbers, and they’re just plain wrong – based on verifiable, reliable sources (like the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the US Census Bureau, the California Department of Education, etc…)

I don’t know where the 2019 numbers came from, but in their 2016 study “Teacher Pay Gap is Wider than Ever” study (8/9/16, appendix C.) we see the source of those numbers is a bit obscure and difficult to verify – because it’s listed as “author’s analysis of pooled 2011-2015 Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group data” – which really gives nothing to refer to as to how they did that analysis.

In contrast, we can also look at two very simple numbers.

I’m using 2017 data because that’s the latest year numbers are available in both data sets.

For teacher wages, the CA State DOE’s annual “J90” report, which shows for 2016-17 the average CA teacher made $79,128/year.

https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/fd/cs/

For comparable graduate wages, the US Census Bureau’s American Communities Survey data for 2017 shows the average CA resident with a bachelor’s degree makes $60,940, with a “graduate or professional degree” makes $85,555.

https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_1YR_S1501&prodType=table

Lastly, in 2016 the CA Legislative Analyst’s Office did a study that found that 42% of teachers have a “masters degree or higher.”

https://lao.ca.gov/handouts/education/2016/teacher-workforce-012016.pdf

If we take the bachelor’s number of $60,940 and the advanced degree number of $85,555 and adjust that assuming 42% have bachelor’s degrees, that comes out to a comparable average of $75,216.

Which means the teacher average of $79,128 is 5.20% higher than the average comparably educated California resident.

These are facts, from reliable sources. What other conclusion is there?

And of course this analysis does not factor in the fact that teachers typically are contracted to work 1200 hours or less a year (look at your local district’s union contract if you don’t believe that) – compared to 2080 hours for private employees.

And it also does not factor in the fact that in education, districts in CA are currently required to contribute 16.28% of their salary to their pension plan and the state contributes 9.6%. .

Adding the district’s 16.28% to the state’s 9.6% means the employer contributes a total of 25.88% to the employee’s pension.

Contrast this to private employees, who typically receive a 3% match on their 401k plus the 6.2% contributed by their employer to Social Security – a total of 9.2%, or about 11.5% less than teachers get in retirement compensation.

Now, exactly where do we get the idea that teachers are underpaid compared to comparably educated Californians?

Again, may be true for other states, but most definitively not true for CA – and since their conclusion is demonstrably wrong for CA I would be very suspect about their other state numbers…

Replies

Dan Plonsey 5 years ago5 years ago

The hours that we are contracted for, which you say is 1200, is ~33 per school week. However, teaching is one of those professions which requires work far beyond contract hours! My contract only covers those hours I'm in the classroom. Preparing lessons, grading, lunch and after-school tutoring, communicating with students and parents -- all of these are outside our contract hours. I work 50-55 hours per week, which various studies have said is fairly … Read More

The hours that we are contracted for, which you say is 1200, is ~33 per school week. However, teaching is one of those professions which requires work far beyond contract hours! My contract only covers those hours I’m in the classroom. Preparing lessons, grading, lunch and after-school tutoring, communicating with students and parents — all of these are outside our contract hours. I work 50-55 hours per week, which various studies have said is fairly typical. So I am paid for only 2/3 of my work — at best. And while I am aware that the average worker reports working over 40 hours/week, I have also seen estimates that only 3 of those hours are productive, whereas teachers’ hours are almost all productive.

But the real point is that wealth continues to be transferred steadily to the very wealthy from all the rest of us. And though I’m a teacher, I believe that we need solutions that help all of us, not just teachers.

Todd Maddison 5 years ago5 years ago

"My contract only covers those hours I'm in the classroom." Which is how it works for every job, everywhere. Everyone in the world who is "paid for time" is only paid for the time they are required to be at work. Certainly there are jobs that are paid "by the job" (i.e. on completion no matter how long it takes), but if you are in a job that has defined work hours, that's what you're … Read More

“My contract only covers those hours I’m in the classroom.”

Which is how it works for every job, everywhere. Everyone in the world who is “paid for time” is only paid for the time they are required to be at work.

Certainly there are jobs that are paid “by the job” (i.e. on completion no matter how long it takes), but if you are in a job that has defined work hours, that’s what you’re being paid for.

You may choose to do additional work, of course – because it’s necessary to keep that job, because you want to impress the boss, because that’s just the way you are – but that extra work is not technically what you’re being paid for.

I know many teachers (we’re having a wake for a teacher who passed away at our house next week, the entire district is invited) and they are certainly hard working, dedicated people.

Meanwhile, actual data, from the actual US Bureau of Labor Statistics, says “Full-time private industry workers work an average of 2,045 hours per year, or about 37% more than public school teachers. This includes time spent working beyond assigned schedules at the workplace and at home.[144]”

https://www.justfacts.com/education.asp#k12_spend_teacher

So let’s not use anecdotal “data” based on what people think, perhaps?

I’m not looking at this as “pay per hour worked” anyway, and I’m not factoring in the plush benefit plans – we could argue over both, but the actual facts based on actual pay records show that teachers in CA make more than comparably educated people in other jobs.

And that’s just a fact.

jskdn 5 years ago5 years ago

I suspect the best measure for comparisons is total employer compensation per hour, which take in all forms of compensation.

“Table 7. State and local government workers, by occupational group: employer costs per hours worked for employee compensation and costs as a percentage of total compensation, 2004-2018–Continued

Primary, secondary, and special education school teachers

Total compensation, Cost per hour worked, December 2018 $66.46”

https://www.bls.gov/web/ecec/ececqrtn.pdf

Very few of the occupations listed pay that high.

Larry Sand 5 years ago5 years ago

A major omission here: Private industry employees work an average of 37 percent more hours per year than public school teachers. This includes the time that teachers spend for lesson preparation, grading, coaching, and other activities. As James Agresti points out, “Unlike less rigorous studies, this data from the Department of Labor is based on detailed records of work hours instead of subjective estimates about how long people think they work.”

tom 5 years ago5 years ago

A lot can be said about this but I'll make it short. While the wage growth looks to be lagging the private sector, seems to me that comparing only wages between teachers and "college graduates" may not be a fair comparison because teachers get things that not all private sector college graduates receive as part of their compensation package. For example, teachers often get paid health care (sometimes during employment and into retirement), … Read More

A lot can be said about this but I’ll make it short. While the wage growth looks to be lagging the private sector, seems to me that comparing only wages between teachers and “college graduates” may not be a fair comparison because teachers get things that not all private sector college graduates receive as part of their compensation package. For example, teachers often get paid health care (sometimes during employment and into retirement), and now have large pension contributions from their employers. The other factor is that teachers do not have to report to work during the 3 months of summer. Teachers can always get a job during the summer especially in this economy, or simply enjoy the peace and quiet! Should the public pay teachers the same as someone else who has to go to work all summer? Some might think so, but not the majority I would think.

Inadequate analysis 5 years ago5 years ago

Shouldn’t the wage gap be between teachers and other government employees with similar education? Government doesn’t pay as well as the private sector, that is well understood. So the gap should be more vs. government jobs, I would think.