Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

As California moves ahead with implementation of its Common Core standards, it is coming up against a major challenge long-anticipated by education leaders: ensuring that teachers across the state know how to effectively teach according to the new standards in math and English language arts.

It’s a massive undertaking, involving over 300,000 teachers in more than 1,000 districts in a geographically dispersed state.

To address the challenge, the California Department of Education, along with the State Board of Education and the association representing county superintendents of education (CCSESA), created a Standards Implementation Steering Committee 18 months ago to encourage the teaching of new standards not only in math and English, but also in science and history in California classrooms.

In addition, “collaboration committees” have been formed for each subject area involving 20 to 25 experts in their respective fields, along with a network of what are called “communities of practice” to promote successful implementation of the standards across the state.

The effort, which includes holding workshops for educators during the school year, has underscored the need for additional teacher and administrator preparation and is raising questions about how long implementation of the new standards should take.

The state adopted the Common Core standards in 2010, and schools and districts began rolling them out to varying degrees in subsequent years. Preparation for teachers and administrators is up to districts to carry out. In the spring of 2015, students began taking a full battery of Smarter Balanced standardized tests aligned with the math and English standards.

“I always had in my mind about 2020,” said State Board of Education President Michael Kirst, referring to the time it would take to reach full implementation. “Now, we’re in 2017. There are places that are way ahead and places that are way behind.”

“What still concerns me and keeps me up at night is the in-depth professional development that we need for all teachers,” Kirst said. “I really want to know what is going on in the classrooms. I thought I would know, and I don’t.”

At a state board meeting earlier this month, California Department of Education officials outlined the work that is being done to prepare teachers to successfully integrate the standards into the classroom. Some board members responded by asking how far along California really is.

Board member Bruce Holaday expressed concern about the lack of data.

“I don’t have an accurate estimate of how far along the implementation is that has taken place,” he said later. “I was not able to really get that information during the meeting, but I continue to hope that we will have a clearer picture of where we are in this process.”

However, Tom Adams, deputy superintendent of instruction with the state Department of Education, told EdSource that the state isn’t charged with monitoring districts’ implementation of the Common Core standards or with assessing how they are doing.

“We do not have the ability to measure that,” he said. “But we do get a sense of how far districts have come based on survey results, test results and accountability results.”

Student test results on the Smarter Balanced tests do show some improvement statewide, though testing experts warn against drawing firm conclusions based on only two years of results.

In 2015, 33 percent of students in grades 3-8 and 11 met math standards on the tests, and 44 percent met English language arts standards. In 2016, scores rose to 37 percent and 49 percent, respectively.

The team of educators working with districts across the state told board members that in many parts of California, teachers and administrators haven’t yet received the kind of high-quality, sustained training they need to successfully teach the more rigorous Common Core math standards. The need for teacher preparation in the new science and history social-science standards was also discussed.

Brent Malicote, director of the state’s professional learning support division, and the other presenters said that training has been inconsistent statewide and that there are differences of opinion about what constitutes high-quality teaching and professional development.

Efrain Mercado, policy director for the California County Superintendents Educational Services Association, told the board the math and science committees found that those offering professional development to teachers also needed support.

“We want to make sure the people providing professional learning to the field are also receiving professional learning themselves,” he said.

The committees, he said, are focused on networking and sharing best practices. “There are different approaches in different counties,” Mercado said.

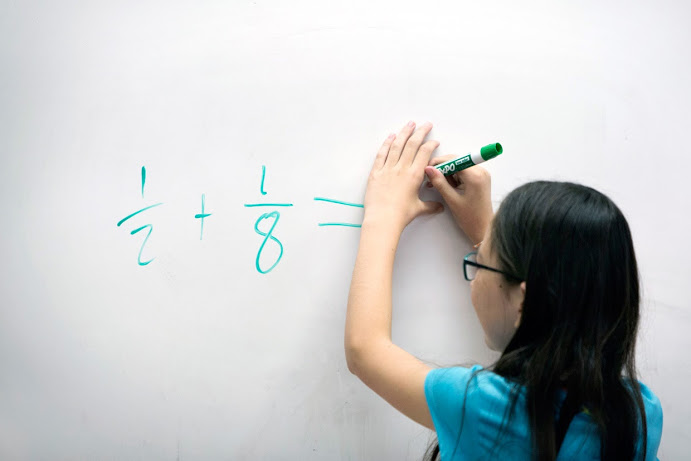

Chris Dell, director of STEM education in the Shasta County Office of Education, told the board that some teachers don’t have the depth of content knowledge necessary to ensure students understand “the why and the where of math, instead of just the how,“ referring to the need to understand math concepts and apply math to real life situations. In addition, Dell said administrators need training so they can “serve as champions for high-quality math instruction.”

Administrators need to know what it looks like to have high-quality math instruction, he said. “I learned that we are in very different places in our understandings and practices.”

Teachers from elementary school to the college level need additional training in Common Core standards because, under previous standards, teachers focused on the memorization of procedures and rules instead of understanding the concepts behind math problems, Dell told EdSource.

Similarly, he said many administrators are still hanging onto “old school thinking” that kids should be practicing the same kinds of problems over and over again instead of learning how math works and applying it in real world situations.

The math collaboration committee identified four focus areas:

Kirst told EdSource that difficulties hiring substitute teachers to cover for educators so they could participate in workshops and other professional development opportunities has forced districts to train teachers before or after school, or to “embed” training during the school day through coaching from mentor teachers. It’s possible that districts’ inability to take teachers off-site for intensive training may have slowed down implementation in some areas, he added.

Nathan Inouye, science coordinator for the Ventura County Office of Education, said the science committee’s goals are similar to those of the math committee.

“We really want to be able to calibrate instruction so what one teacher thinks is high-quality instruction is the same as another,” he said. “The teachers all want to do this right and they want to do it now. The challenge for us is to get out there to help them and support them in that process.”

The science committee plans to survey teachers to monitor implementation of the science standards during the next three years, Inouye said.

Board member Ilene Straus, who represents the board on the Standards Implementation Committee, raised the issue of just how long it would take to fully implement standards. “Some say five to eight years, some say 10, and some say 20 years until we touch all classrooms,” she said.

In a later interview, she said based on her experiences as a principal and district administrator, she believed it takes five to 10 years from the time a teacher first hears about new standards for them to be taught well.

“I would say we have another two to three years for those who have been working with Common Core for several years, and three to five for those who are newer to it,” she said. “I think most kids are taught many of the standards.”

Strauss said she would like to receive information about what makes the biggest difference in implementing high-quality instruction.

“We have some existing places where high-quality professional development is happening and where it’s working,” she said, adding that Long Beach Unified is a good example. “We need to capture those practices and broadly share them.”

A continuing issue is how to pay for professional development for teachers and administrators.

Tom Torlakson, state superintendent of public instruction, asked how much it would cost to ensure districts are able to train teachers and administrators in the new standards. He pointed out that the state provided $1.25 billion for Common Core implementation several years ago, but much of that was spent on technology to prepare for the computer-based tests.

“There was a huge thirst for teachers to improve their practice,” he said.

When the previous math and English language arts standards were adopted in the late 1990s, Torlakson said the state provided hundreds of millions of dollars for professional development. Now, he said, districts must use their Local Control Funding Formula dollars to pay for training as part of their accountability plans.

Torlakson said he doubted the state would provide one-time professional development money in next year’s budget, but he hoped that would be considered in the future.

Mercado said the work of the math and science committees was “jump-started” by funding from the S.D. Bechtel Jr. Foundation. The foundation provided $1.3 million to pay for travel across the state for about 25 members of the math and science committees, as well as for more than 100 members of each of their “communities of practice.”

The English language arts and history-social science committees are seeking similar funding, Mercado said.

One possible source may be federal funds that may come to the state as a result of passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act, or ESSA, Kirst told EdSource.

“All of this is preliminary,” he said of the possible ESSA funding, “but it’s on the table.”

EdSource receives support from the S.D. Bechtel Jr. Foundation. EdSource maintains sole editorial control over the content of its coverage.

The overreliance on undersupported part-time faculty in the nation’s community colleges dates back to the 1970s during the era of neoliberal reform — the defunding of public education and the beginning of the corporatization of higher education in the United States. Decades of research show that the systemic overreliance on part-time faculty correlates closely with declining rates of student success. Furthermore, when faculty are… read more

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Comments (9)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Laura Saunders 7 years ago7 years ago

How do the private schools evaluate the new CAASPP scores when accessing a new application from a student who has been attending a public school in California?

Barry Garelick 7 years ago7 years ago

See also: https://traditionalmath.wordpress.com/2017/01/31/682/

Chris Moggia 7 years ago7 years ago

Currently the state's K-12 data system, CALPADS, does not track information about the progress of Common Core implementation levels. So as the article states, without that data, how can we measure progress towards the goal? I am more hopeful that with the new funding formula and planning process (LCFF/LCAP) that additional data points will be captured. Seven years "IN" to this process and we have some administrators and teachers who still … Read More

Currently the state’s K-12 data system, CALPADS, does not track information about the progress of Common Core implementation levels. So as the article states, without that data, how can we measure progress towards the goal? I am more hopeful that with the new funding formula and planning process (LCFF/LCAP) that additional data points will be captured. Seven years “IN” to this process and we have some administrators and teachers who still cannot articulate the difference between this pedagogy and the previous one. Sure, many can articulate a talking point or two, but if you ask 10 teachers what they are doing differently now than 5 years ago, I would hazard a guess that half would simply shrug their shoulders. If you asked those same 10 teachers to write up an article about the pre- and post-Common Core teaching methods, what would they say?

Doug McRae 7 years ago7 years ago

A core requirement for any end-of-year statewide testing program that will be used to measure the results of instruction, as the Smarter Balanced tests are used in California, is that instruction on the standards (in this case, the Common Core standards) has been implemented at least to a substantial degree before the tests are initiated. This fundamental requirement was ignored by California policymakers when the Common Core Smarter Balanced tests were initiated spring 2015. The … Read More

A core requirement for any end-of-year statewide testing program that will be used to measure the results of instruction, as the Smarter Balanced tests are used in California, is that instruction on the standards (in this case, the Common Core standards) has been implemented at least to a substantial degree before the tests are initiated.

This fundamental requirement was ignored by California policymakers when the Common Core Smarter Balanced tests were initiated spring 2015. The consequences have been substandard, essentially invalid Smarter Balanced test scores, for the last several spring testing cycles and likely also from the coming spring 2017 testing cycle.

Data on the degree of instructional implementation of Common Core standards is not that difficult to obtain. Each Smarter Balanced classroom test administrator, each Smarter Balanced school coordinator, and each Smarter Balanced district coordinator answer on-line survey questions at the end of each testing cycle each year. A few targeted questions on current instructional practices (on Common Core standards) included in this on-line survey would provide a robust database of instructional information at the classroom, school, district, and statewide level to track implementation of Common Core instruction in California over time.

Such an on-line survey was part of the California Smarter Balanced “pilot” test in 2013, as I recall, but it was dropped from the end-of-cycle survey data collected in 2014, 2015 and 2016.

To initiate a statewide testing program used to measure the results of instruction before teachers have been adequately trained to deliver that instruction was a major major error in judgment by California education policymakers. We are now living with substandard test data as a result of that error in judgment, impacting the ability to make quality decisions at all levels. It will take considerable time to correct the consequences of this mis-step.

ann 7 years ago7 years ago

After reading this frighteningly honest article about the vast incompetency in California’s education bureaucracy can you point me to a transcript of this unholy mess?

Replies

Theresa Harrington 7 years ago7 years ago

Ann, here is a link to the SBE meeting: https://youtu.be/7S1sYobwAiE?list=PLgIRGe0-q7Safim1TwdTNlcV7auIbigPr. The discussion of standards implementation is agenda item 3, which starts at about 3:16:00 into the video. However, please note that some of the comments in the story were taken from phone interviews, not the board discussion.

Mike Emerson 7 years ago7 years ago

Theresa, any chance with the Trump administration saying they are done with Common Core standards, and his Education Secretary indicating that she wants to return power to the states, that the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium will go away? As a secondary math teacher, and part-time college math instructor, I am concerned that these math standards are not preparing our students for Math-related degree fields. You can't guess and check your way to building a bridge. … Read More

Theresa, any chance with the Trump administration saying they are done with Common Core standards, and his Education Secretary indicating that she wants to return power to the states, that the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium will go away? As a secondary math teacher, and part-time college math instructor, I am concerned that these math standards are not preparing our students for Math-related degree fields. You can’t guess and check your way to building a bridge. Any chance this nightmare will come to an end?

Replies

Theresa Harrington 7 years ago7 years ago

Mike, We are working on a story about the future of Common Core under the Trump administration. Since the federal government has no authority to abolish the standards, most people to whom we have spoken do not believe it or testing on it will go away in California.

dougliser 7 years ago7 years ago

I doubt it. While I side with the state on just about any issue argued with the Trump administration, I must agree with you that CCSS has been a nightmare in math. The current standards are at least a year behind 1997. Our 8th grade student is finishing the year in Spain as an exchange student, and he is exactly at level coming from a high-scoring suburban California middle school. That would seem fine except … Read More

I doubt it. While I side with the state on just about any issue argued with the Trump administration, I must agree with you that CCSS has been a nightmare in math. The current standards are at least a year behind 1997. Our 8th grade student is finishing the year in Spain as an exchange student, and he is exactly at level coming from a high-scoring suburban California middle school. That would seem fine except he is supposed to be a year ahead here in “accelerated” math. That would mean the non-accelerated class is a year behind Spain. I can’t imagine what is going on in Korea or Singapore. This is a sad state of affairs and nobody seems willing to stand up and address it.