Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

A year ago last spring, I participated in a centennial forum at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, celebrating the publication in 1916 of philosopher John Dewey’s classic Democracy and Education. I shared with that audience my belief that our state’s return to local control through Gov. Jerry Brown’s Local Control Funding Formula initiative is the best example among the fifty states of the principles that Dewey espoused so long ago — using the education of school children to further democratic ideals in local communities.

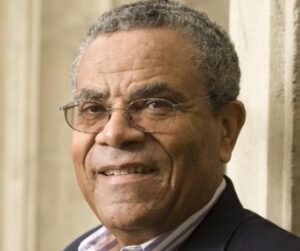

Credit: Courtesy of Claremont Graduate University

Carl Cohn, executive director of the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence

This historic legislation was signed by the governor on July 1, 2013 and included three elements: 1) school finance reform; 2) school governance reform; and 3) the creation of a new state agency, which I now head, called the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, whose purpose is to get the right kind of help and assistance to districts, charter schools, and county offices of education.

Our little shop represents a dramatic shift away from the test, punish and shame of No Child Left Behind interventions to continuous improvement and building staff capacity using what we know about improvement science. Our mantra wherever we go starts with “profound respect for the local level,” and the fundamental belief that, if underserved kids are going to be rescued, it will be done by those closest to them, not by state capitols and the federal government.

We’ve been staffed and hard at work for the past 18 months taking our message of a new kind of state support to all parts of our diverse state, including those places that the media doesn’t regularly cover and that may be hard to get to. In addition to one region of Los Angeles Unified, we’re working in Palo Verde in Blythe near the California-Arizona border, Greenfield in South Monterey County, and Dos Palos Oro Loma in Merced County, as well as Sausalito-Marin City north of the San Francisco Bay Area, Victor Valley in Southern California’s high desert, Anaheim Union High School District in the heart of Orange County and Newark just south of Oakland.

Several years ago, I watched Huell Howser’s popular California Gold episode on public television about his visit to Modoc County exploring our state’s Northeastern most corner — a place that bills itself as “where the West still lives.”

We decided to go to this region of the state that typically gets little attention from policy makers or the media. After a flight to Reno, Nevada, and a three-hour plus drive to Alturas, the only incorporated city in one of the least populated counties of the state, we sat down for dinner at Antonio’s Italian Restaurant on Main Street, near the historic Niles Hotel where we were staying overnight. I chose the meatball and spaghetti dinner special, which included salad and garlic bread for $5.99. (By the way, the meatballs were absolutely the best that I’ve had in a long time.)

The next morning, we sat down with education leaders of Modoc County to listen to their description of the challenges they face trying to improve the life chances of the youngsters in their community. We heard about the opioid crisis, the fact that there are no eligible foster parents in the entire county, that five county mental health positions remain unfilled, that the hardest possible job to fill is that of a school bus driver, and that a youngster needs to drive three-plus hours to find a community college in a state that is pushing college for all. We who live in population centers sometimes take basic amenities for granted. They described deal-breaking interviews for teacher candidates when a spouse finds out that the closest Walmart is more than a hundred miles away.

They also shared heartbreaking stories about heroic youngsters who show up for school every day even if their parents are strung out on meth at home and offering them nothing but neglect. And, they mentioned equally heroic teachers and other school staff members who will constantly go the extra mile for students who need the basics of food, shelter and clothing.

They also talked about a strong sense of grievance that they and their community share: Feeling that government is not working for them, not listening and not paying attention to them. From their perspective, it is doing just the opposite. Their timber industry, which used to employ significant numbers of people, is gone because elites elsewhere decided that they can’t cut down trees. Their ranchers are told how much cattle they can have on their own acreage because environmentalists from distant places want to regulate their lives and their property. No surprise, perhaps, that 72 percent of voters in Modoc County voted for Donald Trump last November, and that the county board of supervisors in 2013 voted to secede from California and join a proposed new state of Jefferson.

While we were there last week, the post-Charlottesville discussions were in full flight nationally underscoring the polarization and great divides in our country. I don’t have easy answers, but I do know that right here in our own state we have places that we need to do a better job of listening to and showing up in if we’re going to come together around the rescue of all school children — a noble purpose to which we’re all committed.

Our trip to Modoc County was a great learning experience for someone like me, who has spent more than four decades working in large urban school districts. I used to buy the conventional wisdom that urban educators faced the biggest challenges in doing their jobs. I’m not so sure about that anymore. I was superintendent of schools in two places where teachers love to live — Long Beach and San Diego — and we never had a problem filling teacher or bus driver jobs. I’m not sure I’d be competitive or want to trade places with the heroic and dedicated educational leaders of Modoc County that I met last week.

Showing up is just a first step. The bigger challenge will be to figure out what the state can do to help educators meet the hopes and aspirations of children and families in these remote regions of California that get far less attention than they deserve.

We’re listening, we’re learning and we’ll be back.

•••

Carl Cohn, formerly superintendent of schools in Long Beach Unified and San Diego Unified and a member of the State Board of Education, is executive director of the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

The overreliance on undersupported part-time faculty in the nation’s community colleges dates back to the 1970s during the era of neoliberal reform — the defunding of public education and the beginning of the corporatization of higher education in the United States. Decades of research show that the systemic overreliance on part-time faculty correlates closely with declining rates of student success. Furthermore, when faculty are… read more

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Comments (4)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

el 7 years ago7 years ago

Thank you for making the trip to Modoc County. I don't necessarily agree that they have identified the correct cause for their grievances, but the truth that they have some great kids and have significant and unaddressed issues in providing a great education to those kids is certainly part of my experience in a different rural region. Bus drivers are a problem, and they're essential to getting rural kids to school. Even spouses who are … Read More

Thank you for making the trip to Modoc County. I don’t necessarily agree that they have identified the correct cause for their grievances, but the truth that they have some great kids and have significant and unaddressed issues in providing a great education to those kids is certainly part of my experience in a different rural region.

Bus drivers are a problem, and they’re essential to getting rural kids to school. Even spouses who are satisfied with the proximity to Walmart might not be able to find a job in the vicinity. Rural areas don’t always have quality, affordable housing that matches to educator salaries, especially if the minimum zoning is 40 acres plus per parcel. Even if the school has internet (no guarantee), the community might not.

Declining enrollment under LCFF is a devilish place to be, financially, and especially if you already were providing special services to your high needs population. There is a lot of declining and/or highly variable enrollment in rural communities.

Dr. Cohn, I hope you will make the opportunity to visit several rural counties, schools, and districts. Each one has a different flavor and set of issues. Just as Palo Verde and Newark differ, so will Humboldt and Lake and Stanislaus and Plumas counties. At each of them, I’ll wager, you’ll find some hardworking people doing some great things successfully as well as plenty of frustration. Plus, what a great excuse to tour our wonderful state with all its different niches.

Karen T. Hilburn 7 years ago7 years ago

Carl Cohn has the unique ability to see beyond “political correctness” and other urban issues! He was an inspiration to all of those in LBUSD who had the privilege to work for him!

Frances O'Neill Zimmerman 7 years ago7 years ago

I have a friend who romanticizes beautiful, sparsely populated, poor Modoc County as an outpost of the Old West, not unlike Dr. Cohn's appreciative account of his visit there. More powerfully to the point, this esteemed educator could be calling from his bully pulpit as executive director of the new "California Collaborative for Educational Excellence" for the proper and transparent use of tax dollars from the Local Control Funding Formula. That measure was sold … Read More

I have a friend who romanticizes beautiful, sparsely populated, poor Modoc County as an outpost of the Old West, not unlike Dr. Cohn’s appreciative account of his visit there.

More powerfully to the point, this esteemed educator could be calling from his bully pulpit as executive director of the new “California Collaborative for Educational Excellence” for the proper and transparent use of tax dollars from the Local Control Funding Formula. That measure was sold to the voters by Governor Jerry Brown more than four years ago, and we’re still in the dark.

Commenter Paul reminds us that Local Control Funding Formula monies are to be spent improving public education for all low-income and English-learner children in California, per Governor Brown’s promise.

I live in San Diego where secrets of the Local Control Funding Formula are still closely held by the superintendent of schools and her labor-elected Board of Education. Citizen “committees” notwithstanding, it is not at all clear where this money is going and under whose direction. There are indications here and in other communities elsewhere that LCFF monies are being applied clandestinely to teacher contract salary raises as the alleged “highest best use” of the dollars.

Teacher salary raises are not what LCFF money was intended for. We need better-training for principals and teachers, much smaller classes for K-12 students, counselors for secondary “restorative justice” detention rooms, English language instructors, after-school tutoring programs – and yes, even bus drivers for rural communities.

Paul 7 years ago7 years ago

"Their timber industry, which used to employ significant numbers of people, is gone because elites elsewhere decided that they can't cut down trees. Their ranchers are told how much cattle they can have on their own acreage because environmentalists from distant places want to regulate their lives and their property." Do you mean the urban elites who contribute the federal and state tax revenues on which California's rural counties are almost totally dependent? The Local Control Funding … Read More

“Their timber industry, which used to employ significant numbers of people, is gone because elites elsewhere decided that they can’t cut down trees. Their ranchers are told how much cattle they can have on their own acreage because environmentalists from distant places want to regulate their lives and their property.”

Do you mean the urban elites who contribute the federal and state tax revenues on which California’s rural counties are almost totally dependent?

The Local Control Funding Formula is meant to address the extra cost of educating children from low-income families, whether urban or rural.

There remains an overall shortage of education funding in this state, and boosting economic productivity is part of the solution. There is no going back to an economy based on resource extraction and subsistence farming. Those activities never did afford working people a high standard of living, and it is silly to romanticize them.

To the aggrieved pro-Trump majority in rural California, I say, just wait till Betsy DeVos has cut federal funding for your public, district-run schools, decimated federal student loan programs, and thrown the doors of for-profit career colleges back open!