Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

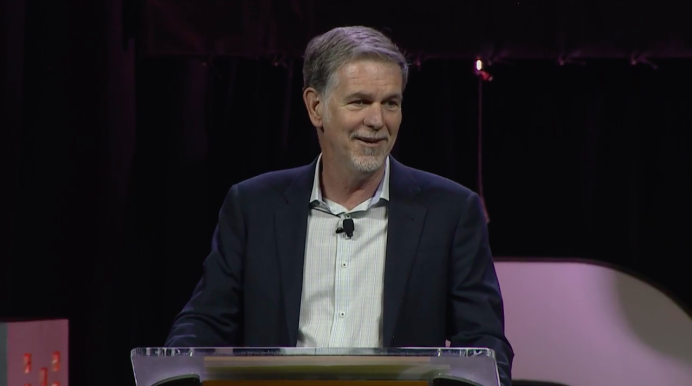

Despite contributing millions to pro-charter forces backing school board candidates in Los Angeles and elsewhere, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings says he doesn’t believe in elected school boards.

It is an argument that the billionaire philanthropist has been making in various forums for years. His latest salvo against school boards that many regard as a bedrock of American democracy came last week in a speech he made to the annual conference of The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools in Washington D.C., attended by about 4,500 enthusiastic charter school advocates, teachers and administrators.

His appearance came just weeks after all three candidates he backed in Los Angeles Unified won seats in school board races that were the most expensive in U.S. history. Some $17 million was spent in the election – with deep pocketed philanthropists easily outspending the California Teachers Association and other teachers unions in the race.

While Hastings directly donated $1,100 each to candidates Nick Melvoin, Kelly Gonez and Mónica García, he contributed nearly $5 million between September 2016 and May 2017 to the advocacy arm of the California Charter Schools Association. The charter group went on to spend nearly $8 million on behalf of the three candidates through its two main campaign finance arms. Garcia, an incumbent, was re-elected in March while Melvoin and Gonez won their runoff races in May.

As the races came to a head, Hastings contributed $1 million to the charter association just days before the runoff election on May 16. Other contributors included wealthy charter backers like billionaire Eli Broad, Gap co-founder Doris Fisher, and former Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan.

Hastings, who as a former president of California’s State Board of Education brings an unusually deep knowledge of education policy to his philanthropic giving, says that school boards are the single biggest impediment to educational improvement in the United States. Elected boards, he said, are prone to instability and frequent change, upsetting educational progress in the pursuit of short-term political agendas. He holds up self-appointed boards like those governing nonprofit charter schools as a far better model. “In a nonprofit, as we get more board members they’re trying to make the organization better,” he said. “They’re not trying to flip-flop it.”

By that he means that an elected official typically is elected on a mandate of change, which often means reversing reforms that are underway, and invariably pushing out the sitting school superintendent.

“What is the fundamental structure of a school district?” he asked. “Well, you’ve got an elected school board that’s elected from the general public and it changes, especially in large urban districts, pretty quickly. And so superintendents change quickly and directions about how we’re teaching change rapidly.”

That creates instability that gets in the way of making steady improvement over time, he argued. “What we see in large urban districts throughout America is a little bit of progress and then a reset, little bit of progress and a reset” Hastings said. “But there is no large urban district that’s continued to get better for 50 years in a row, because of the elected school board … That elected dynamic is what is hurting urban school districts.”

By contrast, he argued, charter schools can continuously improve, because they have a much more stable governance structure. “Governance is the fundamental change with charter public schools,” Hastings said, because charters “are trying to get better every five years – every 10 years you are little better than you were in the past.” That, he said, helps explains the success of some of the best known charter organizations, such as KIPP. “It doesn’t mean every charter school will be great, or every charter school will have great governance,” he said. “Some, of course, are chaotic, but as long as the good ones grow and the great ones prosper, then the average throughout the movement will be incredible.”

Vernon Billy, CEO of the California School Boards Association took vehement exception to Hastings’ critique. “The idea that we should eliminate locally-elected school boards in favor of a secretive system where appointed boards make decisions with public money and no accountability to the voters is an affront to democracy and common sense,” he said. “To suggest that school boards are the primary reason for district instability and superintendent turnover when the research on the subject says otherwise is irresponsible at best.”

In addition, Billy said, “there are countless instances where a board has selected a new superintendent and that board and superintendent have maintained stability by pursuing the district’s existing strategic plan.”

If elected school boards are indeed as hopeless as Hasting’s contends, is he wasting his money by investing in getting candidates elected to them? Netflix turned down an EdSource request to speak to Hastings about his expectations of the candidates he helped get elected to the L.A. Unified board. But presumably he is hoping they will help advance his charter schools agenda.

As he spelled out in his speech last week, he hopes to see the majority of children in the nation’s public schools enrolled in charter schools, something he said he is committed to supporting even if it takes decades to accomplish.

That echoes the views put forward by the framers of the so-called Broad Plan that helped fuel the latest round of charter wars in California. The now moth-balled plan, put together two years ago by the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and other charter school advocates in Los Angeles, was to add 260 charter schools in the district, about twice its current number, and to enroll half of the district’s students in them.

Similarly ambitious expansion plans are espoused by the California Charter Schools Association, when it kicked off its “March to One Million” campaign last year. The goal? To enroll 1 million students in charter schools across California by 2022, nearly double the current enrollment of 600,000.

But at least at this stage, it seems as if Hastings will be disappointed if he is expecting the candidates he backed to move aggressively to expand charter schools.

In interviews with EdSource, the two new members who were backed financially by charter school advocates say they will not push for an increased number of charter schools in Los Angeles.

“Charter school expansion is not something that I am really interested in doing,” said Gonez, who is leaving a teaching job at a Los Angeles charter school to join the L.A. Unified school board beginning July 1. “I want to help support and improve all of our currently existing schools with a primary focus on traditional district schools. With the district’s budget deficit, what we really need to be prioritizing is increasing enrollment in our district schools.”

The way to fix the district is not to push more students into charter schools, she said, “but to invest in and support traditional district schools, so that every neighborhood school is an excellent public school.”

Similarly, Melvoin, who defeated incumbent board president Steve Zimmer, disavowed any effort to expand charter schools, and certainly nothing along the lines of the Broad Plan. “We were very clear with our messaging from the start (of the campaign) that this wasn’t about the proliferation of charters,” he said. “It was not about an artificial number of new charters.”

Instead, Melvoin said he wants the district to look at innovative charter schools and help replicate what they are doing in traditional district schools, rather than creating new ones. “To me the victory over the next few years will not be charter growth, but across-the-board improvement.”

Clearly, charter advocates would prefer to have board members like Melvoin and Gonez, who are receptive toward charter schools, rather than ones who are actively hostile to them. However, board members like Zimmer, who is on the board until the end of June, could hardly be described as “anti-charter.” The board approved almost all of the charter authorization applications recommended by the district’s Charter Schools Division from 2011 to 2016.

While having Melvoin and Gonez on the board may not yield the massive increase in charter schools that Hastings and some other charter advocates would like, they could move them closer to that goal in small increments.

But as Hastings made clear last week, he may well be satisfied with slow progress, especially given his skepticism that anything good will come out of elected school boards especially in urban districts, and that he is committed to a decades-long drive to expand charter school enrollments.

“I’ve been a supporter for more than 20 years, and I will be with you for another 20 and another 20, because it’s going to take a long time,” he told charter advocates. “It’s frustrating but it’s the reality.”

He likened the push to create more charter schools to some of the biggest struggles of the civil rights movement. He pointed out that it took nearly 200 years to implement the notion of one person, one vote. “We have to recognize that human society changes slowly, but it does change, and together we have the joy, the honor, and the excitement of changing our country for the better,” he said.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (7)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Kipp Penovich 7 years ago7 years ago

I think the idea of an appointed board is crazy. The biggest problem that should be addressed with setting up a board is this: How will you correct the board if things start to go wrong? And in asking that, my firm belief is that the "correcting" of a board should be done by the stakeholders that board is supposed to serve. For all the criticisms you can bring on about a publicly elected board, … Read More

I think the idea of an appointed board is crazy. The biggest problem that should be addressed with setting up a board is this: How will you correct the board if things start to go wrong? And in asking that, my firm belief is that the “correcting” of a board should be done by the stakeholders that board is supposed to serve.

For all the criticisms you can bring on about a publicly elected board, the bottom line is that if the board (or individuals on the board) do not behave properly, there will be regular opportunities for the public to change things through the election process. This possibility does not exist in an appointed board (also referred to as “self-perpetuating,” which I find ironic in that this term is also used to describe how a virus behaves. It only cares about its own existence, not what it is doing to the host organism.).

It does require for citizens to be active and informed. That can be frustrating, but I will take that any day of the week over forfeiting my voice in choosing board members. If only ethical, and moral individuals comprised a board, I don’t think it would matter what board structure you had, things would be done in an ethical and moral manner. But I have watched appointed boards appear to have initial good intentions, and then get highjacked by an outside agenda, and then never be able to return to the initial goals because there is no leverage for the public to exert their influence to change things.

Paul Richman 7 years ago7 years ago

Mr. Hastings has been making this argument for a while, and it continues to feel to me both tired and unsubstantiated. Our large urban school districts confront huge challenges. Does having representatives elected from these communities to help set a vision and provide oversight really rise to the top of that list of challenges? Certainly all board members and chief executives need to commit to working well together and in the best interests of … Read More

Mr. Hastings has been making this argument for a while, and it continues to feel to me both tired and unsubstantiated. Our large urban school districts confront huge challenges. Does having representatives elected from these communities to help set a vision and provide oversight really rise to the top of that list of challenges?

Certainly all board members and chief executives need to commit to working well together and in the best interests of the students they serve. Neither elected nor appointed members have the market cornered on that. Many, many elected leaders have distinguished records of community service. Serving on a governing board is difficult work, and often messy. Many organizations and agencies with appointed boards struggle in the same ways as elected boards in order to govern well.

Mr. Hastings is a long-time champion for students and creating greater opportunities for all of them. I respect him for that. But let’s put more energy into creating conditions that lead to healthy, safe and economically strong communities where local schools can thrive. And let’s focus even more on high standards for all students, quality instruction and teacher development, and genuine student and family engagement. Those seem to be a much wiser and research-based recipe for success in California schools both now and in the future, as opposed to eradicating the role of elected local leaders based on a sweeping personal belief that appointed individuals can fulfill the difficult yet vital function of governing complex public school systems better than those individuals who must stand for election.

Gail Monohon 7 years ago7 years ago

Vernon Billy is of course absolutely correct that public school accountability to voters is basic to our democracy, but what percentage of voters is authentically engaged in school decision-making? Until pre-service instruction in education matters becomes the only accepted pathway to election as a school board member, we will continue to have a lamentable turnover of new uninformed trustees, running for a variety of reasons and personal agendas. New board members are often “trained” … Read More

Vernon Billy is of course absolutely correct that public school accountability to voters is basic to our democracy, but what percentage of voters is authentically engaged in school decision-making? Until pre-service instruction in education matters becomes the only accepted pathway to election as a school board member, we will continue to have a lamentable turnover of new uninformed trustees, running for a variety of reasons and personal agendas.

New board members are often “trained” to just go along with the more seasoned members or fall in line with whatever the district administration wants to do. This is NOT government of the people, by the people, for the people; it is theater – a matter of role-playing – and promotes all that is bad about bureaucracies. Being a “team player” does not assure board effectiveness in improving education!

With modern technology at our command, system change is possible: we are now able to reach almost everyone almost instantly with the information they need to participate actively in local and state government. So far, little has been done to harness all the possibilities of the internet and social media, television, and printed news – it has begun, but has a very long way to go.

The California State PTA is doing a marvelous job with outreach. LCFF/LCAP was intended to promote local control through genuine community engagement. Funding must be directed to making continuous open communication a mandated reality in public education. We the people own our public schools, and we must all become more involved and competent in education decision-making.

Paula Campbell 7 years ago7 years ago

If newspaper articles are to be believed, many if not most of the charter schools that are not renewed have serious financial problems. I have read stories about charters with high student achievement, supportive and happy parents and financial practices that have run their schools into the ground. Perhaps if charter boards complied with conflict of interest and open meeting laws, we would not have school board meetings filled with parents touting high … Read More

If newspaper articles are to be believed, many if not most of the charter schools that are not renewed have serious financial problems. I have read stories about charters with high student achievement, supportive and happy parents and financial practices that have run their schools into the ground. Perhaps if charter boards complied with conflict of interest and open meeting laws, we would not have school board meetings filled with parents touting high academic performance and school board members complaining about irresponsible financial practices.

I do understand that charter schools just want districts to comply with their requests and otherwise leave them alone but I do wonder if the timelines and practices outlined in ed code don’t contribute to a confrontational relationship that leads not to problem solving (usually regarding finances) but to charter revocation discussions.

Somehow, somewhere the public’s voice needs to be heard regarding the spending of public money and if charter schools want their boards to be populated by parents and employees with economic interests in the school and wants them to operate out of the public eye, publicly elected school boards need to be involved.

el 7 years ago7 years ago

Neither elected nor appointed board members have any monopoly on good sense, good judgement, or general knowledge. I imagine a survey of California school boards would find good and bad members and boards in both systems. What's important is getting good people, who are serving because they are interested and committed to all the kids in their school system, not people who are coming at it with personal agendas, rigid ideology, or as a stepping … Read More

Neither elected nor appointed board members have any monopoly on good sense, good judgement, or general knowledge. I imagine a survey of California school boards would find good and bad members and boards in both systems. What’s important is getting good people, who are serving because they are interested and committed to all the kids in their school system, not people who are coming at it with personal agendas, rigid ideology, or as a stepping stone to some other position. I think it’s also important that the community have the power to remove people who aren’t working out.

There’s no guarantee that in the general case a mayor or a billionaire philanthropist will be any smarter or any more responsible than a community electorate.

Good training is important. There are trainings available in rules, less so in other areas of policy. Boards that turn over slowly can teach and train new members as they come on, but sometimes you don’t have the right mix of people to do that. Experience does come with time. It could be that more trainings and more opportunities for school board members to mix and learn from each other outside their own boards would be helpful.

There is a lot of chance, but I suggest there are ways to address that. School board races are very low information races and more can be done to make that information available. Even a single person blogging can be influential.

I would like to better understand his specific ideas for how a school board helps and hurts its district. His assertion that good superintendents burn out due to terrible boards might be true, but it might not; the job is large and it is challenging. Not all superintendents should have a long tenure. The idea of “continuous improvement” in a school district forgets how much districts are buffeted by forces outside their control, such as changing enrollments, changes to state and federal law, and a lack of purchase power. “A little bit of progress and then a reset” is also what happens from the state level. I challenge him, for example, to name any time that a single curriculum has been tried or available for even a single K-12 span of 13 years.

We remember the times that didn’t work out. We don’t notice the ones that run smoothly and without conflict. The larger the district, most likely the harder it is to avoid conflict.

Jonathan Raymond 7 years ago7 years ago

Having worked with over 13 school board members in the 4 1/2 years I served as superintendent in Sacramento, I can relate to much of what Mr. Hastings is critiquing. But I'd submit there are a few more options to consider. First, both superintendents and school board members need serious training and development on how to become a committed governance team. Too much is left for chance and is a recipe for … Read More

Having worked with over 13 school board members in the 4 1/2 years I served as superintendent in Sacramento, I can relate to much of what Mr. Hastings is critiquing. But I’d submit there are a few more options to consider. First, both superintendents and school board members need serious training and development on how to become a committed governance team. Too much is left for chance and is a recipe for much of what Mr. Hastings describes. Second, and equally if not more important is an idea that was shared with me by a student at Estobin Torres High School in LA. We should allow 16 year olds to vote in local school board elections. It would be really refreshing to empower and engage students in their own learning. This might add fresh perspective and accountability to the governance role of school boards.

Replies

Louis Freedberg 7 years ago7 years ago

Jonathan Raymond, a former superintendent in Sacramento City, makes an important point. Clearly elected school boards are here to stay in the United States, so that as much as Reed Hastings would like to see them replaced with self-appointing boards like those in nonprofit organizations, including non profit charter schools, that is not going to happen. Just about the only way to diminish their powers would be to have more charter schools with their … Read More

Jonathan Raymond, a former superintendent in Sacramento City, makes an important point. Clearly elected school boards are here to stay in the United States, so that as much as Reed Hastings would like to see them replaced with self-appointing boards like those in nonprofit organizations, including non profit charter schools, that is not going to happen. Just about the only way to diminish their powers would be to have more charter schools with their own boards, and fewer district schools under the direct supervision of the elected school board. Another strategy, as Raymond suggests, would be to be to do more work with elected school board members, and superintendents for that matter, so they become aware of common pitfalls that school boards run afoul of — and that they think more deeply about how to ensure “continuous improvement,’ not only in their schools, but in their districts overall so that they have the long view that Hastings talks about, and a district continuously improves over many years, regardless of changes in board make-up.