Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Special education in California is in “deep trouble,” exacerbated by outmoded concepts and an extreme shortage of fully-prepared teachers, according to Michael Kirst, president of the California State Board of Education.

Kirst said that the state’s special education system – which serves students with physical, cognitive and learning disabilities – is based on an antiquated model and that it needs “another look.”

“Someone needs to sit up and say, ‘We need to update it,'” he said.

Just over 1 in 10 of California’s 6.2 million public school students are in special education programs, at an annual cost of upwards of $12 billion in federal, state and local funds. The number of special education students — along with the costs — has been rising in recent years. But the proportion of special education students varies tremendously among counties — from a low of 7.2 percent in Inyo County to a high of 16 percent in Humboldt County, according to 2015 KidsData figures.

The system is rooted “in a set of ideas from the 1970s, based heavily on legal negotiations and legal rights,” Kirst said, referring to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, the principal federal law governing the field that was first approved by Congress in 1975. He likened IDEA to California’s 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education, which Kirst said also needs a makeover.

Compounding the challenge is the special education teacher shortage, which Kirst said is “the most extreme one we have.” Districts are “scrambling to find people,” he added.

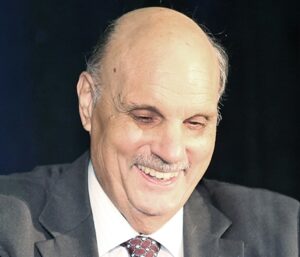

Kirst was speaking at EdSource’s annual symposium in Oakland last week, where he received the organization’s first “Education Champion” award for his contributions to California education over nearly 50 years.

Michael Kirst

Kirst was first appointed president of the California State Board of Education in 1977 during Gov. Jerry Brown’s first term in office. When Brown became governor once again in 2010, he appointed Kirst a second time to the State Board of Education, and he has been president of the board throughout Brown’s current tenure.

When he resumed his post on the state board after a 30-year interregnum, Kirst said reform of special education was on his “bucket list” of things to do.

“But that hasn’t happened in a serious way,” he said. Kirst helped to initiate the Statewide Special Education Task Force that produced a report in 2015 with multiple recommendations for change, including creating a “culture of collaboration and coordination” across numerous state agencies, and giving school districts more control over special education funds.

Note: The 2015 report is no longer available online (note added Nov. 6, 2019).

Kirst said the task force “did a lot of good work,” but he expressed disappointment that not more progress has been made during his tenure.

Echoing Kirst’s remarks, Miriam Freedman, an attorney specializing in special education law and author of Special Education 2.0: Breaking Taboos to Build a New Education Law, said: “The IDEA law did a fabulous job to bring educational opportunity to all children, but it needs a redo to see if it is serving our children and our schools now.”

She said the law was written principally with children who had cognitive impairments and physical disabilities in mind, but currently large numbers of children in special education have learning disabilities. A major problem, Freedman said, is that often these children “only get served after they fail.” “This is a ‘way to fail’ model,” she said. “Children don’t get services until they do poorly in school.”

Kristen Wright, director of the California Department of Education’s Special Education Division, said students with learning difficulties ideally would be identified before they are identified as failing, and as early as preschool, and then taught alongside other students instead of being isolated into special programs.

Carl Cohn, executive director of the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, commended Kirst, along with Learning Policy Institute president Linda Darling-Hammond, for elevating the discussion on special education to “making it a moral imperative to do the right thing.”

Cohn, who co-chaired the special education task force, said that special education changes cannot be isolated from reform of the regular education system. “It is a heavy lift,” he said. “The type of changes that have to take place require major retraining of teachers in regular classrooms,” he said. That’s because large numbers of special education students will likely spend time in those classes, and often teachers there don’t have the training to work with children with special needs.

Kirst described the need for fully prepared special education teachers as “desperate.” California has had a persistent shortage over many years, but according to the Learning Policy Institute, the shortage has skyrocketed over the past two years. To respond to the demand, “we created short–term, quick programs that didn’t spend enough time on how to help train special ed teachers,” Kirst said.

He praised the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, which is chaired by Darling-Hammond, for remedying that and upgrading the standards for a special ed credential. But now “it takes a long time to get the credential, and it is also expensive.” He said it wasn’t clear that the rewards of the job are sufficient to attract and, importantly, retain teachers to the field.

Matthew Navo, superintendent of Sanger Unified near Fresno, who was a member of the special education task force, agreed that recruiting special ed teachers has become hugely challenging, and is likely to become even more so.

Classrooms are increasingly staffed with teachers who are interns or who have provisional permits, he said. “We are begging teachers to go into the (special ed) classroom,” he said. In fact, according to the Learning Policy Institute, “new, under-prepared special education teachers outnumber those who are fully prepared 2:1,” a higher ratio than any other major teaching field.

Some teachers leave the field because of the bureaucratic burdens on teachers to meet the requirements of special education laws. “You get into it to work with kids with special needs and make a difference in their lives, but now 60 percent of your time is managing their paperwork,” Navo said.

The shortage is “killing us in rural school districts with under 2,500 kids that require some effort to commute to and are not able to keep up with salary increases in larger districts,” Navo said. But he said the shortage will be felt across the state. “In the next two years, it’s not going to matter where you are.”

Vicki Barber, the co-executive director of the Statewide Special Education Task Force, said she was encouraged by the fact that education leaders have endorsed the task force’s recommendations, outlined in its report titled One System: Reforming Education to Serve All Students. But she acknowledged the difficulties of reforming a complex system, especially at the school level. “You don’t move an entire program just because a report has been written, even with the best ideas,” she said.

Having issued its report, the task force has been disbanded. The action on a state level has moved to the Advisory Commission on Special Education, appointed by legislative leaders, Gov. Brown and the State Board of Education. Gina Plate, the commission’s chair, applauded Kirst for “shining a light on special education and moving us toward conversations that might not otherwise have happened.”

The overreliance on undersupported part-time faculty in the nation’s community colleges dates back to the 1970s during the era of neoliberal reform — the defunding of public education and the beginning of the corporatization of higher education in the United States. Decades of research show that the systemic overreliance on part-time faculty correlates closely with declining rates of student success. Furthermore, when faculty are… read more

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Comments (30)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Kevin Murray 4 years ago4 years ago

This is a rich article. Anyone have links to 2019/2020 updates, reports and actions in any state, I’d love to read it. Once we move from disability to Universal Design and supporting student needs, waiting for failure to get an IEP will be no more.

frankensein muir 4 years ago4 years ago

Special Ed is looked upon as not needed. Our superintendent thinks just throw them in a class and save the money. These kids are drowning in the regular classrooms, but no one cares. These students have trouble reading as well as retaining what they just read. Comprehension is a problem too. It’s so hard to get through people’s heads.

Sarah 5 years ago5 years ago

Michael Kirst, someone has been standing up and saying, “We need to update it.” The parents of students with disabilities! Sadly, these are the same individuals who are quickly dismissed as selfish, crazy, singularly focused, and fanatical; often by the CA State Board of Education and the Office of Administrative Hearings that has consistently sided with ineffective school districts and put the needs of California’s most vulnerable students in grave danger. If … Read More

Michael Kirst, someone has been standing up and saying, “We need to update it.” The parents of students with disabilities! Sadly, these are the same individuals who are quickly dismissed as selfish, crazy, singularly focused, and fanatical; often by the CA State Board of Education and the Office of Administrative Hearings that has consistently sided with ineffective school districts and put the needs of California’s most vulnerable students in grave danger. If this is not bad enough, parents who do speak up and take costly legal action are frequently the recipient of retaliation by school districts. As well as their children.

It’s time for this state (and others) to have a thorough lesson on the subject Return on Investment and Statistics. The cost of providing the necessary educational support to students with disabilities so that they can achieve the best possible outcome by the time they reach age 22 versus the present system and paying millions of dollars in support over the course of a lifetime to individuals who were denied the necessary resources needed to become independent? Where do we begin? It’s mind-boggling.

Philip G WILLIAMS 5 years ago5 years ago

Is there anything happening in this specialed funding world, legislatively? In Oakland, I think reform in special education funding might be the quickest way to free up money in the general/local fund. Across California, it's consistently listed as one of the two main problems, along with employer pension contributions. Although the price tag for this reform will be considerable, it would still be less than the cost of "Full and Fair Funding", which I estimate at … Read More

Is there anything happening in this specialed funding world, legislatively? In Oakland, I think reform in special education funding might be the quickest way to free up money in the general/local fund. Across California, it’s consistently listed as one of the two main problems, along with employer pension contributions.

Although the price tag for this reform will be considerable, it would still be less than the cost of “Full and Fair Funding”, which I estimate at about $12.5 billion.

Since 1998, urban school districts like Oakland and LA have been hit very hard by the loss of students to charters, while their SPED populations have grown. Since AB 602 funding is on the basis of total ADA, not SPED student numbers, OUSD has seen a decline of about 30% in ADA since the early 2000s, while SPED numbers have stayed the same or risen. For Oakland, the general fund contribution has risen from about $15 million in 2004-05 (my estimate) to $34 million in 2013-14 to over $50 million in 2018-19. While not the answer to all our problems, this level of increased funding would certainly make a big difference for OUSD.

I would love to talk to someone about this issue.

Peter Dragula 5 years ago5 years ago

Been a teacher for more than 20 years, 15 as Educational Specialist, taught resource, mild/moderate, moderate/severe, general ed k-12. One district I worked for had been out of compliance for 10 years. The problems are systemic. One major problem is the "idealistic" approach that all students should be equal or can be; or that all students will and can go to college. Not true. The system and those that determine … Read More

Been a teacher for more than 20 years, 15 as Educational Specialist, taught resource, mild/moderate, moderate/severe, general ed k-12. One district I worked for had been out of compliance for 10 years. The problems are systemic. One major problem is the “idealistic” approach that all students should be equal or can be; or that all students will and can go to college. Not true. The system and those that determine direction need to watch “The Myth of Averages” TedTalk, and realize that all students are unique and there is no “average”. Students with disabilities are not all the same. The system that tries to create singular goals, like all kids will go to college, or “No Child Left Behind” is creating a “Win/lose” system. Alternative paths to graduation should be created and allowed. The competition for a diploma puts enormous pressure on students and families with disabilities that in turn put pressure and increased litigation on teachers and the system. Ironically, even students that have no evident disability are more likely to find that their education may not get them a job when they graduate, because the alignment of the needs of society and schools are not on par. Finally, students that are in Moderate/Severe programs are at a disadvantage in comparison with student on college tracks because there are few if any programs for the disabled after they leave the public school system. After 22, all of my students went to group homes or to live with their parents, until they could no longer care for them. Public schools now provide the mental and health services that the federal and state governments used to provide, but rarely do now. It is only when a student is so severe and the school is threatened with law suits that other support services may be proposed. Our society is repeating the mistakes made in the past and just not dealing with the challenges. It is all about the money and less about the students.

Hillary Holwell 6 years ago6 years ago

I taught in special education for almost 20 years and recently retired because, quite frankly, I was burned out. More and more children with learning disabilities were being identified and funneled into the special education system AFTER they failed. This road to failure was and is completely unnecessary and detrimental to all children, parents, and educators. The overall problem with the special education system is that it seems that, once you enter … Read More

I taught in special education for almost 20 years and recently retired because, quite frankly, I was burned out. More and more children with learning disabilities were being identified and funneled into the special education system AFTER they failed. This road to failure was and is completely unnecessary and detrimental to all children, parents, and educators. The overall problem with the special education system is that it seems that, once you enter the system, you can never “get out.” This is not what special education should be. We should be building inclusive models where all children are mainstreamed as much as possible and not warehoused in categorical programs. Having watched the service delivery models descend into litigious minefields between parents, administration, and educators, I finally gave up the fight. I could no longer stomach what I saw and the adversarial position I was placed in repeatedly engendered extreme burnout. If you want more special educators then stop this madness. Cut down on the paperwork, put safeguards in place for kids BEFORE they fail, allow us to actually teach and not meet, and make district offices responsible for the administration and development of all IEPs. This would alleviate the stress placed on the teaching staff and promote better teaching and better outcomes for students with special needs. Let the district offices deal with the many unhappy and litigious parents who press their rightful agendas and leave teachers out of this quagmire.

Replies

Jay 5 years ago5 years ago

You cannot mainstream a child with learning disabilities or delayed cognitive ability, speech or any child with apraxia and dyslexia! They need more programs to suit every category, which will never happen in public schools. More funding, more money for teachers and staff. It’s actually pretty disgusting how our current district is failing my son who has autism! All because the district will not find more programs and services. Instead a majority of children are … Read More

You cannot mainstream a child with learning disabilities or delayed cognitive ability, speech or any child with apraxia and dyslexia! They need more programs to suit every category, which will never happen in public schools. More funding, more money for teachers and staff. It’s actually pretty disgusting how our current district is failing my son who has autism! All because the district will not find more programs and services. Instead a majority of children are mainstreamed because they’re just barely meeting a goal, that otherwise would be looked upon as needing intensive support in a private special education class setting.

barnettdon 6 years ago6 years ago

I agree that special education needs drastic reform especially in public schools where I find attention to students with special needs especially lacking.

Mark D 6 years ago6 years ago

Special education teaching is unattractive because of "case management" duties. Nearly all special ed teachers are expected to manage 10-28 students' Individual Education Plans (IEPs). When this model was first adopted, this was a manageable duty, but with the continued increased legal requirements, case management is a fulltime job. There is no time to work with the kids or plan classes, and all teachers went into the field to teach and help … Read More

Special education teaching is unattractive because of “case management” duties. Nearly all special ed teachers are expected to manage 10-28 students’ Individual Education Plans (IEPs). When this model was first adopted, this was a manageable duty, but with the continued increased legal requirements, case management is a fulltime job. There is no time to work with the kids or plan classes, and all teachers went into the field to teach and help children, not to be bureaucrats. Special ed administrators don’t care about kids, or at least most come off that way, and only care about paperwork. This is caused by litigious parents and an overzealous state compliance regimen. Many special education teachers quit when they find out working with kids is an afterthought.

Linda Fassberg 6 years ago6 years ago

With SB277 the number of kids needing special services will only increase.

MrT 6 years ago6 years ago

Does anyone ever ask why so many children with special needs? Are we talking about autism spectrum here?

Bill 6 years ago6 years ago

The bureaucratic teaching credential system keeps intelligent teachers away. Paying $100,000 to a university so you can do what you already know how to do is ludicrous. These programs are full of failed teachers and actually create bureaucratic teachers who are more concerned with reports and paperwork than kids. Limiting the ability of schools to attract great teachers makes little sense. It’s not important to our students whether their teachers went through a teaching credentialing program; … Read More

The bureaucratic teaching credential system keeps intelligent teachers away. Paying $100,000 to a university so you can do what you already know how to do is ludicrous. These programs are full of failed teachers and actually create bureaucratic teachers who are more concerned with reports and paperwork than kids.

Limiting the ability of schools to attract great teachers makes little sense. It’s not important to our students whether their teachers went through a teaching credentialing program; all that matters is that they get the very best teachers that we can give them. Our communities, schools and students deserve the highest-quality teachers, not merely the ones with a paper certificate.

JM 6 years ago6 years ago

Having worked in the special education for 15 years, I have worked with some decent special education teachers and some horrible ones. The issue isn't about there being a shortage of teachers, or outdated laws; in my opinion it is about lack of understanding of students with special needs. I have talked with many teachers who have time and again said they didn't receive any classes on behavior management, or what working with the special … Read More

Having worked in the special education for 15 years, I have worked with some decent special education teachers and some horrible ones. The issue isn’t about there being a shortage of teachers, or outdated laws; in my opinion it is about lack of understanding of students with special needs.

I have talked with many teachers who have time and again said they didn’t receive any classes on behavior management, or what working with the special education population means during their credentialing program. It was more academic learning and not behavioral/emotional learning on this particular population. When I first learned about this, it infuriated me, yet I understood why some teachers could not ‘handle’ these behaviors. But it wasn’t just about teachers, it was class aides, administrators and outside liaisons who all lack understanding, empathy and knowledge. Not only do the laws perhaps need to be reviewed again, but training manuals need to be provided, and credentialing classes may need to be reviewed as well.

I truly believe that training people who have the desire to work with this special population, will benefit all and is part of the solution and not the problem. One can’t expect to throw in an inexperienced person to work with special needs people and succeed. They might be doomed to fail. I have witnessed it. As a result, this lack of training results in abuse.

Nancy LaCasse 7 years ago7 years ago

The Statewide Special Education Task Force was an inclusive group of parents and special education/general education professionals who offered dozens of recommendations to the state on ways to improve the special education system, which is built entirely on federal civil right mandates and case law. The system's problems have been discussed for years and it is widely known that the federal government is a "deadbeat" as far as funding the federal mandate is concerned, and … Read More

The Statewide Special Education Task Force was an inclusive group of parents and special education/general education professionals who offered dozens of recommendations to the state on ways to improve the special education system, which is built entirely on federal civil right mandates and case law. The system’s problems have been discussed for years and it is widely known that the federal government is a “deadbeat” as far as funding the federal mandate is concerned, and the state isn’t much better.

The Statewide Special Education Task Force recommended that the state invest significantly in special education preschool programs; fund the over 130 regional special education local plan areas (SELPAs) more adequately and equitably; and, invest in support for special education and general education teachers who spend every day educating our state’s most vulnerable student population. The real question is when will the Governor and Legislature fund these recommendations and make special education one of the state’s major education priorities?

lenne 7 years ago7 years ago

Thank you for the post, please help save us SpEd teachers!

Don 7 years ago7 years ago

In this article the reporters repeatedly refer to outmoded concepts and laws. What specifically is outmoded besides more students identified as learning disabled compared to time when the laws were written? I'd like some specifics because it is a good subject for an article. As a parent of a SPED student I can testify to the fact that the current system is cumbersome and legalistic as some have alluded to in the article. … Read More

In this article the reporters repeatedly refer to outmoded concepts and laws. What specifically is outmoded besides more students identified as learning disabled compared to time when the laws were written? I’d like some specifics because it is a good subject for an article. As a parent of a SPED student I can testify to the fact that the current system is cumbersome and legalistic as some have alluded to in the article. Perhaps the reporters can provide more info in a follow up article.

Anes 7 years ago7 years ago

Many special education teachers are ready to work after their training, but too many tests like RICA that does not make sense in special education (IEP) for student. Too many tests (like RICA,the Reading Instruction Competence Assessment ) prevent these teachers from getting credential. CBEST and CSET should be enough.

Amanda Drake 7 years ago7 years ago

Universal Designs for Learning in the General Education Classroom is the only real remedy, but that would change the way we train ALL TEACHERS, not just Special Education Teachers. Currently it seems as if this mindset is a paradigm shift, most are not ready for. Many, sadly (out of fear) like their “us & them” separation of general and special education. The truth is, there needs to be no separation… Just my 2¢…

Barry Stern 7 years ago7 years ago

The educational system has failed our 17 yr. old daughter with autism for the reasons outlined in this article, particularly the lack of sufficiently trained instructors and the incredibly bureaucratic nature of the school enterprise. We are scrambling financially to become able to care for her as she becomes an adult. Special ed needs a serious makeover. My recent op-ed calls for breaking off the diagnostic, prescription (IEP) and fund allocation functions from the … Read More

The educational system has failed our 17 yr. old daughter with autism for the reasons outlined in this article, particularly the lack of sufficiently trained instructors and the incredibly bureaucratic nature of the school enterprise. We are scrambling financially to become able to care for her as she becomes an adult. Special ed needs a serious makeover. My recent op-ed calls for breaking off the diagnostic, prescription (IEP) and fund allocation functions from the filling the prescription function. Schools currently do it all, and they cheat like hell to keep costs down, or they misuse the funds. http://www.educationviews.org/increase-federal-special-education-funding-parental-choice/.

Saea 7 years ago7 years ago

I don't mind the paperwork or the time or the kids or their parents or... what I DO mind are administrators who know NOTHING about Special Education or the law, or who are hellbent on "putting parents in their place," as one admin has said, then coming to my IEP meetings antagonistic and confrontational, only to undermine & blame ME for those parents exercising their rights to advocate for their kids. I'm … Read More

I don’t mind the paperwork or the time or the kids or their parents or… what I DO mind are administrators who know NOTHING about Special Education or the law, or who are hellbent on “putting parents in their place,” as one admin has said, then coming to my IEP meetings antagonistic and confrontational, only to undermine & blame ME for those parents exercising their rights to advocate for their kids. I’m they’re for “my kids” and their families who are often confused, worried, or unknowledgeable about their rights. Administrators make my job nearly impossible to do 🙁

Raoul 7 years ago7 years ago

What is there that a general ed teacher needs to know for a given grade level that a special ed teacher does not need to know? Logic and prior practice in CA suggest that a special ed teacher should get fully trained and certified as a general ed teacher, and receive additional specialist training and certification also. Much like a specialist physician getting trained first in the essentials of general medicine and … Read More

What is there that a general ed teacher needs to know for a given grade level that a special ed teacher does not need to know? Logic and prior practice in CA suggest that a special ed teacher should get fully trained and certified as a general ed teacher, and receive additional specialist training and certification also. Much like a specialist physician getting trained first in the essentials of general medicine and then receiving more years of specialty training.

The problem is that current practices and union negotiated contracts will not permit such extensively trained and specialized teachers to be paid significantly more than teachers possessed of minimal general credentials. So who would pay and sacrifice for the additional training when the pay is no more? We could quickly create a shortage of qualified neurosurgeons, who must complete a seven year residency, if we had rules allowing them to be paid no more than general practice doctors who need only a three year training program. We could then wring our hands and talk up ideas on how to interest more doctors in neurosurgery, always avoiding the obvious subject of paying them more.

Replies

Amy 7 years ago7 years ago

It used to be that way (had to get a gen ed credential before you could get a special ed credential) That changed around 1998-99. But society needs to change and genera ed teachers perspective needs to change as well. Gen Ed and Special Ed teachers need to work together. There need to be better laws around a Special Ed teachers "extra" responsibilities because they are much more than the Gen Ed … Read More

It used to be that way (had to get a gen ed credential before you could get a special ed credential) That changed around 1998-99. But society needs to change and genera ed teachers perspective needs to change as well. Gen Ed and Special Ed teachers need to work together. There need to be better laws around a Special Ed teachers “extra” responsibilities because they are much more than the Gen Ed teacher. With IEPs that go from 5pm-7pm at night. All the modifications needed for curriculum. And don’t forget teaching it self. Oh — and data collection on all the goals…..and the list goes on and on!

Mchael Gerber 7 years ago7 years ago

Prof. Kirst, Stanford policy academic and current California school board president, is a potent “influencer,” an insider despite his academic credentials, who thinks special education policy needs a remake. What gets mentioned, at least by the author of this article, is cost and numbers of children, special education teacher shortages, and some notion that the foundational ideas of IDEA are old-fashioned, “antiquated,” a residue of the 1970s. I agree that special education is expensive, … Read More

Prof. Kirst, Stanford policy academic and current California school board president, is a potent “influencer,” an insider despite his academic credentials, who thinks special education policy needs a remake. What gets mentioned, at least by the author of this article, is cost and numbers of children, special education teacher shortages, and some notion that the foundational ideas of IDEA are old-fashioned, “antiquated,” a residue of the 1970s.

I agree that special education is expensive, if you are comparing the price of apples versus the price of oranges. In the absence of human-replacing teaching machines, I can’t see how special education — which centers on necessary resources — could not be more expensive than general education. Of course, one could easily argue that too few resources are expended in general education.

I’ll also agree that a lot of kids get special education, although California serves proportionally fewer than some much smaller states. But how do we understand how to interpret numbers without more information about need? The answer isn’t straightforward.

Teacher shortages? I’m not sure what the argument is here? We don’t sufficiently support training or pay competitive salaries and so, what? We should remake special education so services match the inadequate available pool of teachers? Really?

As for old-fashioned ideas, well yes, I agree the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment is old. “Antiquated”?

BRITT FERGUSON 7 years ago7 years ago

It was with great disappointment and sadness that I read your article. I’d like to comment on some issues you raise, please. I agree, it is likely that special education teachers are not fully prepared. Many work on “intern” credentials, meaning they are teaching having perhaps just started and definitely NOT having completed their teacher preparation. A number of years ago California changed credential requirements so that it is no longer required that … Read More

It was with great disappointment and sadness that I read your article. I’d like to comment on some issues you raise, please.

I agree, it is likely that special education teachers are not fully prepared. Many work on “intern” credentials, meaning they are teaching having perhaps just started and definitely NOT having completed their teacher preparation. A number of years ago California changed credential requirements so that it is no longer required that a special education teacher have a basic, general education credential (multiple or single subject). In short, they don’t have the gened basics of teaching. Given these two facts is it surprising that we are in “deep trouble”?

If we look back out our history, IDEA was actually the re-authorized version of PL94-142 the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. Yes, the provision of education for individuals with disabilities was vastly improved because of the civil rights movement and ensuing legislation. However, the foundational principles remain a sound basis for the provision of services to children and youth with special needs – the principles of a free, appropriate public education, an individualized education plan, and an education delivered in the least restrictive environment.

Perhaps it would be worthwhile to examine the reasons there are too few teachers in special education rather than try to solve a problem without understanding it. Ill prepared, too much paper work, insufficient support?

The California Master Plan and PL94-142 were new when I started in education as a new special education teacher. At all times, all children with disabilities, including sensory and physical disabilities, cognitive impairments, and a rage of challenges we called “learning disabilities” were provided for. Yes, how and the quality to which they were provided for varied from district to district, as it does today.

But, from the outset, it was always intended that the general education teacher modify and adapt in order for each child to succeed in their classroom, and only when such modifications and adaptations were not sufficient was special education to be considered. The old discrepancy formula was intended to identify students who were not able to achieve according to their potential but it relied heavily on intelligence testing. Response to Intervention and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support are now used to alleviate the need for intelligence testing and minimize the need for the child to fail before support can be provided.

But herein lies the conundrum. How do we know that a child has a learning difficulty, especially as early as preschool, unless the child is trying but not succeeding at something (in other words “failing”)?

This, indeed, is a commendable statement: “it is a moral imperative to do the right thing.” Regrettably “the right thing” can be a matter of opinion, albeit professional opinion, and definitions of “the right thing” vary among the professionals.

As part of a continuum for the provision of services to students with special needs, the collaboration model where special and general education teachers work together in the classroom, such as by co-teaching, is so important. This model would is akin to practices in the field of medicine wherein the general practitioner and specialist doctors consult and work in unison for the benefit of their patient, an essential model because the generalist cannot be expected to have the advanced training and skills of every specialist in the field of medicine…or in education.

You write, “To respond to the demand, “we created short–term, quick programs that didn’t spend enough time on how to help train special ed teachers,” Kirst said.” This is by far the most true statement in this article. What immediately comes to mind is the old saying, “Buy cheap, buy twice”.

The adoption of the current TPEs is another issue. I wonder, is the state trying to compensate for teachers ill-prepared under the current practices? Compensate by micro-managing teacher preparation and requiring a lengthy (45 elements) laundry list of expectations which teacher preparation institutions are required to meet for the privilege of offering a CTC approved credential program? Perhaps relinquishing some control and allowing greater say to those who actually prepare teachers (universities and colleges) would result in better prepared teachers…something to think about.

Let’s not focus on the length of time to acquire the credential or the expense of the education. If we are concerned about attrition, rather, let’s look at the context in which the new teacher is expected to perform. Does this environment support the Education Specialist in doing what he or she knows to be ethical and appropriate practices? Does administration provide sufficient time for general and special education teachers to co-plan and co-teach? Is there meaningful staff development for general education teachers each year, with support and follow-up? Does the school or, better yet, district adopt meaningful interventions and provide sustained, long-term support for faculty to master the requisite skills and apply them with students, or do we try to revise and reform every 2-5 years, throw out what we’ve been doing and start over? How do teacher feel about that?

And where are the students in all of this? Taught by ill-prepared special education teachers? Sitting in a general education classes where many teachers do not know how to provide for their needs, don’t know where to go for help, and even if they do know where to go for help they may be not skilled at collaborating with the specialist? Are our students waiting for a political system to make political decisions while school continues to fail? In the same way that we want to give districts more control over funds, let’s give those who prepare teachers, the universities and colleges, more control over what to teach and how to prepare teachers. Trying to just cover (not master) 45 elements in the time frame expected of a credential program is not a solution.

Sayitok 7 years ago7 years ago

And what about the significant acrimony? Lawers, advocates, lawsuits… why would anyone want to face the meanness that can occur?

Wayne sailor 7 years ago7 years ago

Good article. We can help. Check out the CASUMS partnership work with the SWIFT Education Center and the Butte County Office of Education operated by the Orange County Department of Education.

Ann 7 years ago7 years ago

I am concerned that Mike and/or Edsource -both seem unlikely-seem unaware of the $30 million and 3-year Scaling up Multitiered systems of Support (SUMS) CA Dept Ed funded project based in Orange and Butte counties and working statewide - it received not even a mention in this article. It's been underway a year plus, addresses the old issue of 'waiting for kids to fail' and operationalizes both evidence-based practices and many of … Read More

I am concerned that Mike and/or Edsource -both seem unlikely-seem unaware of the $30 million and 3-year Scaling up Multitiered systems of Support (SUMS) CA Dept Ed funded project based in Orange and Butte counties and working statewide – it received not even a mention in this article. It’s been underway a year plus, addresses the old issue of ‘waiting for kids to fail’ and operationalizes both evidence-based practices and many of the recommendations of the SPED state task force, for which I was the Ed Prep CoChair. CTC has already moved ahead with the new credentialing with new standards in MTSS for gen ed and CDE has funded SUMS, in collaboration with the SWIFT project. Progress is occurring. One thing we need is more on the teacher prep support end- Our decimated faculties at CSUs, from which I just retired, have not come near to being able to gear up with new positions- At CSUEB, they are still 2 tenure track faculty where we were 5 in sped in 2009-, and prospective teachers lack vehicles for support such as the CSUaple loan forgiveness program that the state also deleted in the recession. These areas need attention. Thank you for the article.

Jonathan Raymond 7 years ago7 years ago

I’ll never forget my first school year day as superintendent in Sacramento. After arriving at a school via bus and greeting parents and staff and children as I walked across the court yard, one parent grabbed my arm and encouraged me to go visit a certain classroom before I left. It was a special day class for children with autism. As I was leaving the classroom, I asked the teacher “do these children ever get … Read More

I’ll never forget my first school year day as superintendent in Sacramento. After arriving at a school via bus and greeting parents and staff and children as I walked across the court yard, one parent grabbed my arm and encouraged me to go visit a certain classroom before I left. It was a special day class for children with autism. As I was leaving the classroom, I asked the teacher “do these children ever get out and mix with other students in the school?” “Oh no,” she replied. “My students couldn’t handle that.” Really, I thought. My own children’s experiences in school taught me differently, and as I visited each school in my first 90 days I always asked to go see the special day classes. With few exception what I saw were children isolated in a classroom with an over representation of boys and young men of color.

And so we began a systemic effort to change this practice in Sacramento and move toward an inclusive practice model centered around special education teachers and regular education teachers co-teaching in the same classroom. How powerful when these teaches plan together and train together. When done well it’s difficult to dinstinguish between the two. At the heart of this work, like so much in education, are the belief systems of the adults doing this work. Do they believe children can learn and excel at the highest levels? Or, like that teacher I met on that first school day. A visit to California Middle School in Sacramento shows how such an approach is good for all children.

Kudos to Professor Kirst! He is correct in saying the special education teaching and learning in California is in “deep trouble.” At this point it’s not about “shining a light.” We know what’s broken and we have models within and outside of California on what this teaching and learning could be. It’s now about leadership, priorities, and courage to take action and do what is right for children. How we respond will tell lots about how we value public education.

Paula 7 years ago7 years ago

There is a demand for qualified teachers, yet even special ed. teachers must follow a state mandated guideline for all students instead of an individual educational plan to address the unique needs of students. Why have highly qualified teachers if the purpose is to impose a general plan on students instead of an individual plan?

CarolineSF 7 years ago7 years ago

I know from real life that teachers are very often thwarted by their administrators in attempting to refer students for assessments, because of fears of the cost. No teacher is safe complaining when this happens. And students are very often not receiving the full services specified in their IEPs for the same reason. It's also common for parents/guardians to refuse to allow their children to be assessed, even as other parents/guardians are desperately trying … Read More

I know from real life that teachers are very often thwarted by their administrators in attempting to refer students for assessments, because of fears of the cost. No teacher is safe complaining when this happens. And students are very often not receiving the full services specified in their IEPs for the same reason.

It’s also common for parents/guardians to refuse to allow their children to be assessed, even as other parents/guardians are desperately trying to get their children approved for special-education services.