Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Click to enlarge

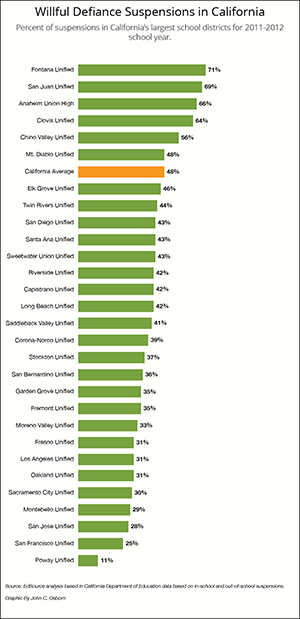

An EdSource analysis has found dramatic differences among the state’s largest school districts in their reliance on the controversial category of “willful defiance” of school authorities as a reason to suspend students.

In a review of 2011-12 data of in-school and out-of-school suspensions for the 30 largest districts in the state, EdSource found that four districts used the category of willful defiance as a reason to suspend students about two-thirds of the time, while nine districts relied on it a third or less of the time. Overall, almost half – 48 percent – of the suspensions in the state were for willful defiance in 2011-12, the most recent data available from the California Department of Education.

Fontana Unified, east of Los Angeles, used willful defiance of school authorities as the reason for 71 percent of its suspensions – the highest among the 30 districts. San Juan Unified near Sacramento was close behind at 69 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, Poway Unified, near San Diego, cited willful defiance in only 11 percent of its suspensions, the lowest among the 30 districts.

The data do not explain why these differences exist. But some districts, such as Poway, attribute their low rates of suspension for willful defiance to their use for many years of alternative approaches to student discipline that favor methods such as restorative justice – which require misbehaving students to make amends to the people they have harmed. Officials at Fontana and San Juan say they are starting to introduce alternative approaches such as conflict mediation to reduce their reliance on the willful defiance category.

The analysis comes as the use of willful defiance to suspend students has come under fire from the Legislature and advocacy groups such as Public Counsel, a public interest law firm based in Los Angeles, which argue that the category is too subjective and vague and has led to disproportionate suspensions based on race or ethnicity. Willful defiance has been used as a reason to suspend for a variety of behavior issues, from a student who sleeps in class to one who screams and cusses a teacher. The section of the law defining willful defiance also includes disruptive behavior.

“If you have a roomful of people and ask them what willful defiance means, you’ll have as many answers as there are people there,” said Isabel Villalobos, coordinator of the Student Discipline and Expulsion Support Unit for Los Angeles Unified. “It is just a catch-all to lump all sorts of kids together that is not appropriate.”

Los Angeles Unified, the state’s largest district, eliminated willful defiance this year as a reason to send students home, and San Francisco Unified is considering a similar policy. Los Angeles relied on willful defiance for 31 percent of its suspensions in 2011-12 – at the lower end for usage among the 30 districts, the analysis showed.

Schools are also under increased pressure to address the issue because discipline policies – including how many suspensions, for what reasons and to which students – are being spotlighted as one of the primary ways to measure “school climate.” Under the state’s new school finance and accountability laws, districts must create a Local Control and Accountability Plan that sets goals and priorities in eight areas, including ways to improve school climate, a broad term that includes how often students are suspended or expelled. Districts must adopt a three-year accountability plan and update it annually.

Laura Faer, an attorney with Public Counsel, said advocates are hopeful that the new accountability requirements will “give districts an opportunity to have a real dialogue about school climate,” including their approaches to discipline.

Suspending students for minor offenses is a “knee-jerk reaction that is not a solution to the problem,” Faer said. “Now the student is even further behind in school, is more angry and more alienated. We can do better in California; we can be leaders in making the change.”

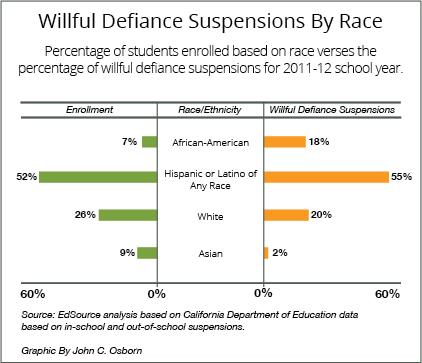

EdSource’s analysis of statewide willful defiance suspension data also showed a racial disparity in rates of suspensions, with African American students the most likely to face suspension and Asian students the least. Asian students make up 9 percent of the school population in California but account for only 2 percent of the willful defiance suspensions, the analysis showed.

African Americans, on the other hand, accounted for 18 percent of willful defiance suspensions statewide even though they made up only 7 percent of enrollment.

White students, like their Asian counterparts, also were underrepresented among willful defiance suspensions – 26 percent of the school population but only 20 percent of willful defiance suspensions. Latinos were slightly overrepresented – 52 percent of the population but 55 percent of suspensions for willful defiance.

A district-by-district analysis by EdSource showed that African American students also were overrepresented in suspensions for willful defiance in all but two of the 30 largest districts – Montebello Unified and Santa Ana Unified. Latinos were overrepresented in willful defiance suspensions in 19 of the largest districts.

Some districts, such as San Francisco Unified and San Jose Unified, had a low number of suspensions for willful defiance, but African Americans and Latinos were still overrepresented compared with white and Asian students. For example, in San Jose, white students accounted for 26 percent of enrollment but only 9 percent of willful defiance suspensions in 2011-12, compared with Latinos, who made up 52 percent of enrollment and 79 percent of willful defiance suspensions.

“We’ve seen this discrepancy for a number of years,” said Dane Caldwell-Holden, director of Student Services for San Jose Unified. “I wish I could tell you why.”

He expects the number of suspensions as well as the disproportionality to go down as more staff are trained in alternative approaches and parents become more involved. The district now offers a 12-week course on parenting for parents of students who are having the most behavior problems.

In 2011-12, African American students made up only 11 percent of enrollment but nearly half (47 percent) of willful defiance suspensions in San Francisco Unified. Thomas Graven, head of Pupil Services, said the 2012-13 numbers will show that overall suspensions have plummeted, but the district is still disproportionally suspending African American, Latino and special education students.

This disproportionality is one of the reasons the district is considering eliminating willful defiance as a reason to suspend.

Disproportionality based on race and ethnicity was cited as one of the primary reasons that legislators began focusing on disciplinary issues three years ago. In the 2011/2012 legislative session, lawmakers passed a number of bills regarding discipline, including Assembly Bill 1729, introduced by Assemblyman Tom Ammiano, D-San Francisco, which emphasized alternative means of correction, such as restorative practices, instead of suspension or expulsion for all offenses. The bill did not specifically address the use of willful defiance.

In 2014, legislators are expected to consider AB 420, the second attempt by Assemblyman Roger Dickinson, D-Sacramento, to eliminate willful defiance as a reason to expel a student and to restrict its use in suspensions. His first try, AB 2242 in the 2011/2012 session, was passed by the Legislature but vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown, who said disciplinary decisions should be left up to local districts.

Laura Preston, a legislative advocate for the Association of California School Administrators, or ACSA, has lobbied in the past against laws that would restrict administrators’ ability to discipline students. But she said her organization realizes that alternative disciplinary approaches can help districts achieve a positive school climate, as required under the new funding law, and is working with advocates about how to implement change.

“We are also looking into restructuring our professional academies with information and training on alternative school discipline,” she said, as well as incorporating workshops on this issue in all of ACSA’s major conferences.

EdSource did follow-up interviews with districts at each end of the spectrum about their discipline policies. Some districts that did not rely as much on willful defiance said they had been implementing alternative disciplinary policies for a number of years. Others who used willful defiance often, such as Fontana Unified and San Juan Unified, were just beginning to do so, district officials told EdSource.

“We don’t think it’s (use of willful defiance) a good thing; we are working hard to change,” said Linda Bessire, director of Pupil Personnel Services at San Juan Unified. “We are well aware of the legislation and discussions. We are trying to look at prevention and intervention before we get to the suspension.”

The passage of AB 1729 spurred Fontana Unified into reviewing its approach to discipline, said Dawn Marmo, coordinator for Child Welfare and Attendance in the district.

“We’re working with the student and family to keep the student in school,” she said, using strategies such as parents shadowing their student to help keep behavior problems in check, conflict mediation and referrals to counseling.

“Ever since we heard about the new law, we’ve had a mindset change,” Marmo said. “It is absolutely a culture change.”

However, others defend the use of willful defiance, saying it gives teachers a classroom management tool for handling misbehaving students. Others say that having strict rules regarding defiant behavior, including the use of suspension, helps create a more respectful and positive school culture.

For example, Clovis Unified suspends almost two-thirds of its students for willful defiance, but its director of Education Services, Scott Steele, defends his district’s reliance on that category.

“We feel very strongly that if a student is willfully defiant, we hold them accountable for that,” Steele said. “We create a structure that is very clear on the consequences.”

Steele acknowledged that “you have to be careful about (using) willful defiance – you can take it too far.” For example, he said, not doing homework or doodling in class is a classroom management issue, not a reason for suspension. On the other hand, if a teacher asks a student to do something and the student refuses, that behavior could lead to a suspension for willful defiance if it happens more than once, he said.

Almost two-thirds of Anaheim Union High School district’s suspensions were for willful defiance, though the district’s overall suspension rate was low. Rick Martens, director of Student Support Services, partially attributed the high rates revealed in the EdSource analysis to the district’s new data collection system. When a student was suspended for another, more serious issue, such as a drug offense, willful defiance was also listed as a reason, he said, thereby distorting the data. Martens is working to correct the problem and hopes to have more accurate data for 2012-13.

Poway Unified, Montebello Unified, San Francisco Unified and San Jose Unified – which the EdSource analysis found were the four districts among the state’s largest with the lowest rates of suspensions for willful defiance – have been implementing alternatives to suspensions and expulsions for a number of years.

Of the 30 largest districts, Poway with 11 percent had by far the lowest rate of suspensions for willful defiance and disruptive behavior in 2011-12. The next closest was San Francisco Unified with 25 percent.

Poway has been using a restorative justice approach for a number of years, said district spokesperson Jessica Wakefield. Under restorative practices, students must take responsibility for their actions and make amends to the school community. For example, if a student disrupts a class, he can write an apology to the teacher and perhaps stay after school to help the teacher prepare for the next day. Teachers and administrators work with students and their families to get at the root cause of the misbehavior.

Todd Cassen, principal of Westview High School in Poway, said he has always refrained from using suspension for minor disciplinary issues.

“Our time is better spent attempting to connect students to their campus,” he said.

Art Revueltas, deputy superintendent at Montebello Unified, where less than a third of suspensions are for willful defiance, said he believes today’s students need to be taught how to behave and teachers need to learn how to discipline students.

For the past 10 to 15 years, the district has been revising its approach to discipline, focusing on the smaller things that affect school climate, such as cussing on campus.

“You have to set expectations and be consistent,” he said. “Suspending for willful defiance is the lazy man’s way.”

Graven from San Francisco Unified worked as a principal and vice principal before taking over Pupil Services. Building a relationship with each student prevents defiant behavior such as mouthing off in class, he said. “Teachers greet kids at the door and know all the students by name.”

Managing routines well, such as where students should sit, also prevents disruptive behavior like fighting over seats. “I didn’t get into this job to be a policeman,” he said. “I got into this job to teach and support kids.”

San Jose Unified – which has slightly more than a quarter of suspensions for willful defiance – has also focused some of its teacher trainings on alternative approaches to discipline.

Sheri Holt, an instructional coach at San Jose Unified, says she experienced an “aha” moment during a professional development workshop when the trainer said: “If students are having trouble reading, you teach them to read. If they’re having trouble with math, you help them. If they are having trouble with behavior, you punish them. What’s wrong with this picture?”

Research analysis for this report was conducted by Lisa Chavez. Contact Susan Frey, who covers school discipline. Sign up here for a no-cost online subscription to EdSource Today for reports from the largest education reporting team in California.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (5)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Frances O'Neill Zimmerman 10 years ago10 years ago

First of all, your description of "restorative justice" discipline mentions a student apology to the teacher -- quite the opposite of a Los Angeles Times story on this subject some months ago which described the need for teacher to apologize to suspended student in front of the class. The LAT story featured one offending African-American male high school student who was an outspoken advocate for "restorative justice" and his photograph. Let's hear from cultural anthropologists on … Read More

First of all, your description of “restorative justice” discipline mentions a student apology to the teacher — quite the opposite of a Los Angeles Times story on this subject some months ago which described the need for teacher to apologize to suspended student in front of the class. The LAT story featured one offending African-American male high school student who was an outspoken advocate for “restorative justice” and his photograph.

Let’s hear from cultural anthropologists on this subject, not vote-seeking state legislators and local school boards. We all know what socio-economic and ethnic groups are disproportionately represented in “willful defiance” suspensions.

It will take additional better-trained educators and counselors representing a broader cross-section of ethnicities, more hands-on involved principals, smaller class-sizes K-12 of kids of all types, before there will be genuine education in what a teacher friend of mine called “the culture of school.” We know what’s needed: we just don’t fund it.

Paul 10 years ago10 years ago

Thanks for the response, Susan, and sorry for the typos. I was composing on a tiny touch screen, in the cold!

Stephen A. Montgomery 10 years ago10 years ago

There was a time when such problems were solved with “the board of education.” Beyond political beliefs is there any evidence that using corporal punishment in dealing with unruly kids actually causes harm and what evidence is there that expulsion actually accomplishes anything, political correctness not withstanding.

Susan Frey 10 years ago10 years ago

The charts include both in-school and out-of-school suspensions. We will update the information in the charts to clarify that. Regarding Latinos, although they are only slightly overrepresented statewide, they are disproportionally suspended by substantial percentages for willful defiance in a number of school districts, including San Jose Unified, which is mentioned in the article. In a few districts, white students are also overrepresented, but typically not by a large percentage.

Paul 10 years ago10 years ago

First, a question about the charts and statistics: since "willful defiance" (and the other grounds for suspension) enumerated in the Education Code can be used to justify administrator-initiated out-of-school suspensions of 1 to 5 days, as well as teacher-initiated in-school, out-of-class suspensions of 1 to 2 days (self-contained classroom) or periods (departmentalized), do the data on willful defiance refer to out-of-school suspension only, or to in-school suspension as well? Now, some usual and new objections... 1. The … Read More

First, a question about the charts and statistics: since “willful defiance” (and the other grounds for suspension) enumerated in the Education Code can be used to justify administrator-initiated out-of-school suspensions of 1 to 5 days, as well as teacher-initiated in-school, out-of-class suspensions of 1 to 2 days (self-contained classroom) or periods (departmentalized), do the data on willful defiance refer to out-of-school suspension only, or to in-school suspension as well?

Now, some usual and new objections…

1. The first chart shows no problem with reslect to Latinos. Willful defiance isn’t being used to suspend Latino students more often than would be expected. This is a very important piece of good news, given that Latinos are the dominant ethnic minority group in California public schools.

2. Does anyone have systemic data on the validity of the suspension decisioms? If the students involved did indeed engage in willful defiance/disruptive behavior, would the overrepresentation of African Americans indicate a problem with the law on student discipline, or simply a lack of discipline among the specific students who were suspended? Would changing the law solve the latter problem? Are there variables outside the control of the public schools that might explain discipline problems?