Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

The current overhaul of California’s student testing program is skipping, for now, the California High School Exit Exam, the one test that’s truly high stakes. If students don’t pass, they don’t receive a high school diploma.

Gov. Jerry Brown has said he will sign Assembly Bill 484, which, as EdSource Today has reported, would suspend the current California Standards Tests in English language arts and math for grades 3 to 8 and 11. In its place, schools could give students a practice exam aligned to the new Common Core standards currently under development.

AB 484 makes no mention of the high school exit exam, called CAHSEE. The California Department of Education also hasn’t yet addressed the test’s future, other than to say that the exam will be administered to the class of 2014 and, possibly, beyond, even though the questions will still be pegged to the state standards being replaced by Common Core.

“The future of CAHSEE remains unclear; it’s an ongoing discussion during this time of transition,” said education department spokeswoman Pam Slater.

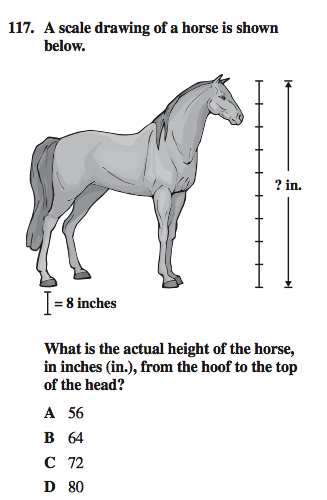

A math question from the California High School Exit Exam. Source: California Department of Education

Not just CAHSEE, but the entire state assessment system is in transition. In a January 2013 report, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson described, in detail, all the tests that will need to be developed in every subject and for all students, including English learners and those with special needs, to align with the Common Core State Standards, a national set of educational standards that have been adopted by 45 states.

“I think that there will be changes to the entire landscape of assessments in California,” said Assemblywoman Susan Bonilla, D-Concord, author of AB 484. “Included in that entire plan will be the high school exit exam.”

Bonilla said the Department of Education will develop proposals for the revamped testing and assessment system over the next few years following an extensive public process. In the interim, academic help for students having difficulty passing the exit exam is dwindling.

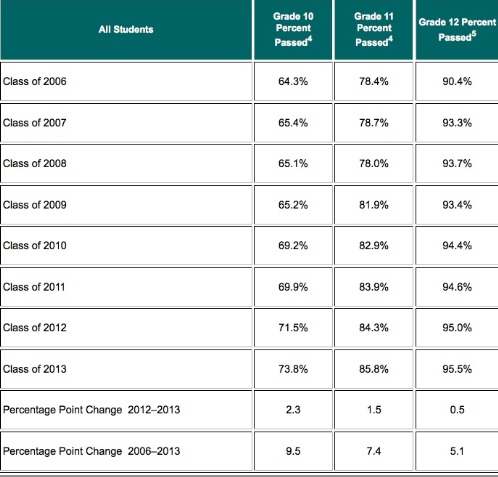

Estimated cumulative percentage of students in the classes of 2006-2013 that passed the high school exit exam by the end of their senior year. Source: California Department of Education

With a few relapses along the way, scores on CAHSEE have increased since 2006, the first year that it counted toward graduation; the exam was field tested beginning in 2001 and was supposed to become a graduation requirement for the class of 2004, but lawsuits delayed the start.

The class of 2013 had the highest success rate to date, with 425,911 students – or 95.5 percent – passing both the math and English language arts sections of the test. The 4.5 percent who didn’t pass add up to slightly more than 20,000 students who didn’t receive diplomas.

Legislators established a California exit exam in 1999 when they approved SBX1 2 with overwhelming bipartisan support. The bill, by former State Sen. Jack O’Connell, D-Santa Barbara, who voters later elected as state superintendent of public instruction, mandates that students pass a two-part proficiency test in mathematics and English language arts, by the end of 12th grade as a requirement for graduation. They have multiple opportunities to take the exam, starting in 10th grade and continuing for two years after their senior year in high school; once students pass a section, either math or English, they don’t have to take that part again.

CAHSEE math questions are set to 7th and 8th grade standards with some Algebra tacked on. English language arts tests 9th and 10th grade material.

Until 2009, school districts were required to provide additional instruction for students who had not passed the test by the end of 12th grade, by letting them remain in school for a fifth year or through a special CAHSEE tutoring class. This was required under Assembly Bill 347, introduced in 2007 by former Assemblyman Pedro Nava, D-Santa Barbara. The bill settled Valenzuela v. O’Connell, a class action lawsuit filed in February 2006 against the State Board of Education and then- state Superintendent O’Connell, alleging that some students, especially those in low-income districts, were not receiving an equal opportunity to learn the material included on the test.

The settlement was essentially upended in 2009, when the state gave districts more flexibility to spend previously earmarked “categorical” funds in any way they wished. The change eliminated mandated spending on two programs that funded CAHSEE interventions, one for summer school and the other for intensive instruction during the academic year. A majority of districts have since used the money earmarked for the exit exam intervention for different programs, according to a 2011 survey by the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

In Sacramento County, for instance, only two districts – out of nine with high schools – are still offering the supplemental instruction for students, said Sherry Arnold, who monitors CAHSEE intervention at the Sacramento County Office of Education.

“In the beginning, every high school district took the money and observed the regulations,” Arnold said. Some of the seven districts may still provide services, but since they flexed the funds, they no longer have to report to her office how they spend the money.

Most of the students who don’t pass the exit exam are in special education programs or are English learners, like Cyndia Velarde, who was in the class of 2013 at James Lick High School in San Jose. She arrived in California from Guadalajara, Mexico, during middle school. Although she still has difficulty with English, Velarde passed all her classes and said she did well on all the CAHSEE practice tests, so she was shocked when she couldn’t pass the real thing. Velarde said she took the test about six times between her sophomore and senior years, but in the end she couldn’t graduate with her classmates.

“I (hadn’t been) worried about getting my diploma,” the 19-year-old said. “I was going to get my diploma and I was going to move on.”

Instead, she went to graduation as a visitor to see her friends, and left depressed. Velarde said she’s dreamed of getting a high school diploma since coming to the United States. She asked her high school counselor if she could stay for a fifth year, but somehow that never worked out. She doesn’t want to stop trying to pass but doesn’t know how to proceed. She had never heard about adult education or community college classes solely to help students pass the test.

A high school degree is important, she said. “If I have that I will feel more proud and will be able to get a job.”

High school diplomas increase earnings by thousands of dollars. In California, employees with diplomas earn a median annual salary of $27,485, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s nearly $9,000 more than workers who never graduated from high school. They’re also less likely to be unemployed.

Velarde’s case is “exactly the type of situation (the Valenzuela case) was designed to address,” said attorney Brooks Allen with the ACLU of Southern California.

Allen says he can’t understand why the state would allow districts to back away from intervention programs while still requiring students to pass the test. “How can you really be denying this really critical lifeline for so many students?” he asked.

It’s not clear how many students are affected by the declining resources for CAHSEE. The Human Resources Research Organization, a 60-year-old research and consulting firm, known as HumRRO, has been contracted by the state to evaluate the exam since it was first developed, and even researchers there don’t have all the numbers.

“It’s been a little frustrating that we haven’t been able to get very good data,” said Lauress Wise, HumRRO’s principal research scientist, who has been analyzing the state’s exam data for a dozen years.

Wise said that of the 20,000 or so students in the class of 2013 who didn’t pass the exam last year, no one knows how many of them have met all other requirements for graduation or how many of them would not have graduated anyway because they didn’t have enough credits. HumRRO estimates that about half the students do keep trying to pass the test after their senior year, but how many pass is another unknown because the student database, the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS) can’t track kids once they leave school. The unique student identifier given to each student by the data system isn’t used by colleges or the Employment Development Department; like most official agencies, they use Social Security numbers.

Researchers do know that by the time students are in high school, it may be too late to do much to help them pass the exit exam, especially for disadvantaged students. Reviews of middle schools that collaborate with high schools have found that “they do a little better at closing the gaps on CAHSEE for minority students,” Wise said. HumRRO is conducting more research into successful middle school programs this fall. Studies by the Public Policy Institute of California determined that students in fourth grade who are English learners are already at a slight disadvantage for passing the high school exit exam.

That still leaves open the question of what to do about the test in the next few years. Although there have been no formal discussions, some ideas under loose consideration include scrapping the test and using the Smarter Balanced tests being developed for the Common Core standards, said State Board of Education President Michael Kirst. Because the new assessments are computer adaptive, meaning that the level of difficulty of the questions changes based on a student’s previous answer, the test could possibly be set to a level that is commensurate with the current exit exam.

That may not be as easy as it seems, said Richard Duran, a member of the state department of education’s technical advisory group working on CAHSEE and an education professor at UC Santa Barbara. The new computer adaptive tests haven’t even been field tested yet. “We have to give that a chance to see how it operates,” Duran said.

The ultimate decision will be based on policy, not technology, Duran said.

“The real matter is how is state policy going to address the meaning of the high school diploma,” he said. “I think it’s a good time to ask these questions and I think it’s a very confusing time.”

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (30)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Guadalupe Maldonado 9 years ago9 years ago

I am a high school student from AV high school in Lancaster CA. I have all my high school credits that I'm supposed to have; I have 241 and you need 230 to graduate. I wasn't able to graduate because I didn't pass the CAHSEE test. I am 19 and I'm still trying to get my diploma, but I mostly would like an answer to whether students from the class of 2014 will be able … Read More

I am a high school student from AV high school in Lancaster CA. I have all my high school credits that I’m supposed to have; I have 241 and you need 230 to graduate. I wasn’t able to graduate because I didn’t pass the CAHSEE test. I am 19 and I’m still trying to get my diploma, but I mostly would like an answer to whether students from the class of 2014 will be able to get their diplomas.

Replies

Michael Collier 9 years ago9 years ago

Guadalupe, If Gov. Jerry Brown signs SB172 you will be able to get your diploma beginning Jan. 1.

Here is the link to the latest EdSource story on this subject:

http://edsource.org/2015/bill-allowing-diplomas-for-students-who-failed-exit-exam-goes-to-governor/86521

Shanay 9 years ago9 years ago

I don’t think its fair that the ones from 2012 that actually finish all there credits and graduating, but didn’t pass one part of the exit exam can not received a high school diploma !but yall letting the ones from 2015 on up get a diploma not fair not on bit.

Lindsey 9 years ago9 years ago

I've been trying since 2008 to get my high school diploma. I was suppose to graduate 2005 due to personal reasons I didn't graduate but I did go back to school I have all my credits but because of the chasee I can't receive my diploma. I have passed the English and I keep failing the math I'm now 29 and still trying. Who can I get in contact with to receive my diploma if … Read More

I’ve been trying since 2008 to get my high school diploma. I was suppose to graduate 2005 due to personal reasons I didn’t graduate but I did go back to school I have all my credits but because of the chasee I can’t receive my diploma. I have passed the English and I keep failing the math I’m now 29 and still trying. Who can I get in contact with to receive my diploma if it’s taken away? When will we know if it’s going to be taken away?

Mohammed Msallam 9 years ago9 years ago

Hi, I’m a high school student.

And I have been in the United States for 2 years, and this year I’m a senior class of 2015. I took the CAHSEE two times I passed the math but I didn’t pass the English I missed 10 points for the English even though I know that I did great in the test so I hope that the questions be a little easier and thank you!.

ana flores 9 years ago9 years ago

for some reason i had been taking te cashee and i havent pass it , i wish we wood not have to take it ,we will have more chances to be someone in life , not droping of school just because we can pass the cashee , maybe they will be more profecional ppl working in a better place then working for a minimum….. i think we work more then what we get paid….

jose ramirez 9 years ago9 years ago

Hello i had a question about am from the class of 2006 and i did not pass the exam but had all my requierments i even got more creditis then what i need it so if thirs any change in the future well it help us to the class of 06?

cahsee User 9 years ago9 years ago

2015 is the year I would have graduated. I just got my results and now feel like killing myself I feel like if the whole world has just collapsed on my shoulderso. Take the cahsee out it really puts pressure and gets you frustrated and gives you these feeling of suicide.

jessica 10 years ago10 years ago

I feel like I was a victim of the Chasee test, I took the test I believe two times and passed the English part with no problem and had to retake the math portion in my senior year of 2006 and failed. I completed all my high school requirements and got my certificate of completion and was allowed to walk but I felt like I was ripped off. I worked hard and completed high school … Read More

I feel like I was a victim of the Chasee test, I took the test I believe two times and passed the English part with no problem and had to retake the math portion in my senior year of 2006 and failed. I completed all my high school requirements and got my certificate of completion and was allowed to walk but I felt like I was ripped off. I worked hard and completed high school but because of this one test it determined me not to receive my diploma. Since then I have always felt like I was in limbo on what to do. I recently saw an article that a lot of states are giving the people that were in the same situation I was in a chance to receive there diploma and make it right after all these year. I feel like California should do the same and present the people with there diploma that met all the requirements with there high school diploma so they move forward with there lives and allow them to do what they were ment to do and want to in the work force.

CarolineSF 11 years ago11 years ago

As a recent high school mom, I can tell you that based on my kids’ and their friends’ experience, the CAHSEE is much, much, much less rigorous than the CSTs. Pretty much only kids with truly major academic issues — or else language or a disability connected with lower achievement — failed to pass the CAHSEE.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

Does anyone know whether a passing grade on the CAHSEE correlates with a specific percentile result on the CSTs?

Replies

Doug McRae 11 years ago11 years ago

Passing scores for CAHSEE were set to be equal to “basic” on STAR CSTs when CAHSEE was first developed, and attempts have been made to adjust CAHSEE passing scores each year to maintain that relationship. I think HumRRO independent evaluation reports have documented this relationship over time.

Ed 11 years ago11 years ago

CAHSEE was not aligned specifically to our math and ELA standards; it tests students in grade 10 on basic math with a touch of algebra and basic English. Also, CAHSEE was never originally contemplated or intended to fulfill the requirements of NCLB, it just a convenient tool for that purpose. The purpose of CAHSEE was to ensure that our high schools stopped the practice of graduating students who are unable to read their own diploma. … Read More

CAHSEE was not aligned specifically to our math and ELA standards; it tests students in grade 10 on basic math with a touch of algebra and basic English.

Also, CAHSEE was never originally contemplated or intended to fulfill the requirements of NCLB, it just a convenient tool for that purpose. The purpose of CAHSEE was to ensure that our high schools stopped the practice of graduating students who are unable to read their own diploma. Sadly, the rigor of the exam was reduced to the level it is today because mass failure was undesirable, especially by those who seek the protection of adults over kids. Ironically, it has become one of the only assessments that has any meaning in the real world because there are real consequences associated with failure to pass.

CAHSEE may not survive because those who oppose accountability want it eliminated, and those who support accountability mock it for its lack of rigor. One can hope that a replacement, like end of course exams, would be implemented. But, that will not happen under AB 484.

Replies

Gary Ravani 11 years ago11 years ago

No offense, El, but that assertion about HS graduates not being able "to read their own diploma" is one not backed by any empirical evidence. It is one of those thoughtless cliches tossed out "supported" by the "crisis in the schools" lobby. One of those canards constantly referenced by the propaganda industry pushing privatization of the schools. Another motive here, is to constantly divert public attention from the fact that the term "accountability" has … Read More

No offense, El, but that assertion about HS graduates not being able “to read their own diploma” is one not backed by any empirical evidence. It is one of those thoughtless cliches tossed out “supported” by the “crisis in the schools” lobby. One of those canards constantly referenced by the propaganda industry pushing privatization of the schools. Another motive here, is to constantly divert public attention from the fact that the term “accountability” has been demeaned to mean school accountability exclusively. There is a boatload of sound information, some of it from CA’s own testing vendor, ETS, showing that variability in school achievement results can be attributed to school effects for 33% of differences. Outside of school effects account for the other 66%. So, our “accountability” systems require the 33% tail to wag the 66% dog. Hasn’t worked well. As that accountability system is called into question you can see the proponents get more and more hysterical, as in demanding CA’s students get tested on what they are no longer being taught. What is needed is 360 degree accountability. Who should be held accountable for CA being in the bottom five of the 50 states in dollars for K-12 education adjusted for cost-of-living? Teachers? And who should be held accountable for the US being 31st of 32 nations rated by the OECD for child hood poverty? Schools? When the right questions are asked some answers begin to emerge that point to irresponsible actions by those in the highest positions in our economic and governmental hierarchy. There is a certain desperation in making sure those questions don’t get asked.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

If we can believe test data, the tail has grown in length by 60% over the past decade. This means had the body kept up at the same rate, we'd be near 90% 'full-grown', instead of just over 50% dog with a really long tail. That said, even with 66% outside factors, its valid to question why the tail has been growing. And given that ratio, I'll say it again: 'education economists' really need to look … Read More

If we can believe test data, the tail has grown in length by 60% over the past decade. This means had the body kept up at the same rate, we’d be near 90% ‘full-grown’, instead of just over 50% dog with a really long tail. That said, even with 66% outside factors, its valid to question why the tail has been growing.

And given that ratio, I’ll say it again: ‘education economists’ really need to look at what poverty is costing us. I once had a friend describe the difference between living in Europe and America as “a diploma, a health plan, and a bus, in exchange for world domination”

Perhaps public schools are just a sacrificial lamb for some economic ‘lesser good’?

Manuel 11 years ago11 years ago

USA! USA! USA!

We are Number 1! We are Number 1! We are Number 1!

😉

So, is Common Core ObamaCore even if his fingerprints are not on it?

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

IMHO, Common Core is just part of the standard accountability paradigm, where not only the pressure created by the fact that people know someone is paying attention is as or even more important than what is actually measured and taught, but that in order to avoid that pressure 'going stale' it has to be revamped every now and then to remind people that the pressure is still there and expectations are still rising. Where it comes … Read More

IMHO, Common Core is just part of the standard accountability paradigm, where not only the pressure created by the fact that people know someone is paying attention is as or even more important than what is actually measured and taught, but that in order to avoid that pressure ‘going stale’ it has to be revamped every now and then to remind people that the pressure is still there and expectations are still rising.

Where it comes from is beside the point. That said, imho Gobama has little clue when it comes to education policy. I dont necessarily blame him for that, its not a Federal issue. What’s wrong is maybe us assuming he should care, and him pretending that he does.

Gary Ravani 11 years ago11 years ago

“The real matter is how is state policy going to address the meaning of the high school diploma,” he said. “I think it’s a good time to ask these questions and I think it’s a very confusing time.” Yes, indeed, it is a time to start "asking questions." Many questions should have been asked, and reasonable answers sought, prior to moving pell mell into the age of "if it moves test it." This goes for the … Read More

“The real matter is how is state policy going to address the meaning of the high school diploma,” he said. “I think it’s a good time to ask these questions and I think it’s a very confusing time.”

Yes, indeed, it is a time to start “asking questions.” Many questions should have been asked, and reasonable answers sought, prior to moving pell mell into the age of “if it moves test it.” This goes for the entire spectrum of educational policy making in this country, but with high school exit exams most of all.

We do have some key indicators. The National Research Council study on test-based accountability finds exit exams to have had no significant effects on student achievement and more “rigorous” exams contributed to lower graduation rates and, generally, the exams seem to promote more students using GED programs as an alternative to graduation.

The institute for Research on Education Policy and Practice at Stanford in its study specifically on the CAHSEE found the exit exam “lowers graduation rates for girls and students of color.” Also, “among low-achieving girls and students of color, graduation rates decline by nearly 20 percentage points because of the exit exam.”

Pretty devastating.

So what is a likely alternative? How about teachers’ grades? Teachers give innumerable quizzes and tests as well as directly observing what students know and are able to do over the course of a school year as opposed to the one day snapshot provided by tests. They know whether a student has achieved a minimum (or maximum and/or in-beteween) level of proficiency in a subject. There are studies that validate that middle-school grades are sound predictors of high school grades and high school grades are good predictors of college grades.

A good time for questions? Absolutely.

Jerry Matchett 11 years ago11 years ago

One of my strong objections is that it is about "standards" and not "human diversity." Imagine that every great author in the world, as represented by having a book in your local library, was made to adhere to "standards." What human experience is about is diversity - the diverse life experiences of inventors, authors, artists, musicians, etc. Standards should be few and aquisition of diverse abilities emphasized. Otherwise we shall be … Read More

One of my strong objections is that it is about “standards” and not “human diversity.” Imagine that every great author in the world, as represented by having a book in your local library, was made to adhere to “standards.” What human experience is about is diversity – the diverse life experiences of inventors, authors, artists, musicians, etc. Standards should be few and aquisition of diverse abilities emphasized. Otherwise we shall be as similar as bowling pins – no one doing anything worth while.

Kathryn Baron 11 years ago11 years ago

Stephen,

Two bills passed this session address second grade testing.

SB 247 by Carol Liu (D-Glendale), would end the second grade California Standards Test in English Language arts and math and, instead, turn it into a diagnostic assessment that districts can administer, but the state will pay for.

AB 484 by Susan Bonilla (D-Concord), suspends California standardized tests that aren’t required under No Child Left Behind. It does allow districts to administer English language proficiency tests to 2nd graders.

Replies

Kathryn Baron 11 years ago11 years ago

Also, both of these bills are on the governor’s desk. He doesn’t usually announce his intentions prior to taking action, but has said he will sign AB 484.

Stephen Montana 11 years ago11 years ago

This bill intends to suspend California Standards Tests(CST) in English language arts and math for grades 3 to 8 and 11. Does that mean California will continue to test grade 2 with the CST? No Child Left Behind never required California to test grade 2 and I’m hoping grade 2 would be included in the suspension.

Fred Jones 11 years ago11 years ago

The end was definitely the key to this whole story: policymakers need to get out of the weeds and ask the BIG questions, starting with: "What is the purpose(s) of high school?" From there, they will hopefully consider the broad range of skills/aptitudes and dispositions that all students bring to the secondary setting, as well as the various pathways to success in life and career that await them all (hint: not everyone needs a 4-year degree, … Read More

The end was definitely the key to this whole story: policymakers need to get out of the weeds and ask the BIG questions, starting with: “What is the purpose(s) of high school?”

From there, they will hopefully consider the broad range of skills/aptitudes and dispositions that all students bring to the secondary setting, as well as the various pathways to success in life and career that await them all (hint: not everyone needs a 4-year degree, and therefore college-prep may not be the best default curriculum for every secondary student).

Simple acronyms like CAHSEE, A-G, SAT, GPA and API don’t necessarily lead to success for all students, as not all fit nicely through these top-down, force-fed filters and bottlenecks.

Oh, and one nitpicky observation about this line in this excellent report:

“High school diplomas increase earnings by thousands of dollars”

Causation/correlation problem. H.S. Diplomas don’t necessarily “increase earnings” … just that those who don’t earn one tend to earn thousands less than their graduated peers. The same could be said for 4-year degree earners: those who slog through this much formal schooling to get a degree tend to be the kind of people who will work hard to earn more in their careers, but it’s not necessarily their degree in History or French Lit that produces the extra earnings.

Replies

Kathryn Baron 11 years ago11 years ago

Hi Fred,

Thank you for putting the diploma/income issue in context. Whatever is behind it, the correlation is rather stark.

CarolineSF 11 years ago11 years ago

The correlation is absolutely clear, but the press still needs to take care not to confuse correlation with causation. Just to state the obvious, being raised in poverty correlates directly with failure to complete high school and also with lower income as an adult. Being raised in economic privilege correlates directly with likelihood of finishing college (which, just as a reminder, is crushingly expensive), and also with higher income as an adult. Undoubtedly, the college degree vs. the … Read More

The correlation is absolutely clear, but the press still needs to take care not to confuse correlation with causation.

Just to state the obvious, being raised in poverty correlates directly with failure to complete high school and also with lower income as an adult.

Being raised in economic privilege correlates directly with likelihood of finishing college (which, just as a reminder, is crushingly expensive), and also with higher income as an adult.

Undoubtedly, the college degree vs. the lack of a high school diploma amplify the effect of poverty vs. privilege on earnings as an adult, but still, what the actual data show is purely correlation.

A study that actually showed causation would need to control for those circumstances and many more.

Doug McRae 11 years ago11 years ago

Very comprehensive post on CAHSEE, Kathy. One of the lost opportunities over the past half dozen years for CAHSEE, however, is the lack of coordination with STAR that would have gone far toward reducing the gross overtesting of high school students by our entire statewide testing system. STAR end-of-course tests for E/LA and Algebra could have be used for "early qualification" for the CAHSEE high school graduation requirement, thus allowing CA to eliminate upwards of … Read More

Very comprehensive post on CAHSEE, Kathy. One of the lost opportunities over the past half dozen years for CAHSEE, however, is the lack of coordination with STAR that would have gone far toward reducing the gross overtesting of high school students by our entire statewide testing system. STAR end-of-course tests for E/LA and Algebra could have be used for “early qualification” for the CAHSEE high school graduation requirement, thus allowing CA to eliminate upwards of 80 percent of current CAHSEE test administrations. That would save not only testing time, but also a bundle of wasted test administration dollars. CDE staff, the SSPIs, and the State Board have ignored this potential efficiency for our statewide testing program for a half dozen years, and when it was suggested to the author of AB 484, the response was “484 is about STAR, we’re not going to expand it to CAHSEE.” I guess bureaucratic silos are alive and well in Sacramento. I mention this because when it comes to new common core tests, it is highly unlikely that the SBAC grade 11 test will include high school graduation minimum skills questions in its computer-adaptive item bank. Instead, the grade 11 SBAC test will target college readiness . . . stuff like Algebra II questions, so says SBAC literature. But, it is likely that SBAC middle school tests will have questions that measure the mimimum skills needed for high school graduation. Thus, one of the options on the table for the future of CAHSEE should be an Early Qualification program where scores from middle school common core tests pre-qualify students for high school graduation requirements, thus allowing for a greatly reduced CAHSEE program requiring high school testing only for students not pre-qualified via middle school tests. To consider this type of common sense good testing policy, we’ll have to break down a few silo walls in Sacramento.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

“The real matter is how is state policy going to address the meaning of the high school diploma,” he said. “I think it’s a good time to ask these questions and I think it’s a very confusing time.” Thats an important point. We have 95% passing rate, yet claims that the need for remediation is at an all-time high. It would be good to have a discussion why that is (including the rebuttal points against the … Read More

“The real matter is how is state policy going to address the meaning of the high school diploma,” he said. “I think it’s a good time to ask these questions and I think it’s a very confusing time.”

Thats an important point. We have 95% passing rate, yet claims that the need for remediation is at an all-time high. It would be good to have a discussion why that is (including the rebuttal points against the remediation claim).

In addition, given the proficiency rates at high school levels for existing CSTs, and the expected drops for newer assessments, it seems difficult to imagine that using either of those as a replacement for CAHSEE would be a good idea.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

jerk.. 😉

perhaps the goal is to train them for the absurdities of ‘real life’.. ?

el 11 years ago11 years ago

Because I'm a jerk, I can't help but point out that people who are actually knowledgeable about horses know that you don't measure the height of a horse at the top of the head.. which moves. You measure them at the withers (the high point of the shoulder). Certainly part of what is tested here is learning to answer the question that was asked (no matter how foolishly) rather than the question that you think they're … Read More

Because I’m a jerk, I can’t help but point out that people who are actually knowledgeable about horses know that you don’t measure the height of a horse at the top of the head.. which moves. You measure them at the withers (the high point of the shoulder).

Certainly part of what is tested here is learning to answer the question that was asked (no matter how foolishly) rather than the question that you think they’re asking. I am just repeatedly surprised by how often, in a quest for relevance, test questions are created in a way that goes against the intuition and knowledge of someone with actual expertise in that subject.

Replies

Paul 11 years ago11 years ago

Interesting. The horse question is biased because of its incidental linguistic and national content. If questions like this can creep into state assessments -- ostensibly reviewed by experts for quality and equity -- just imagine the junk that finds its way into textbooks, school district benchmark tests, and teacher-created tests. Though the dimension arrow at the far right helps, an English Learner's attention might well be diverted to processing the words "hoof" and "head". Given that so … Read More

Interesting.

The horse question is biased because of its incidental linguistic and national content. If questions like this can creep into state assessments — ostensibly reviewed by experts for quality and equity — just imagine the junk that finds its way into textbooks, school district benchmark tests, and teacher-created tests.

Though the dimension arrow at the far right helps, an English Learner’s attention might well be diverted to processing the words “hoof” and “head”. Given that so many of our English Learners count Spanish as their first language, it bears mentioning that neither of these key words is a Spanish cognate.

Though not all English Learners are immigrants, those who are would be at a particular disadvantage if they tried to check their answers for reasonableness — a strategy often taught in math classes. The United States is the only country in the world to use Imperial units, such as inches. Even the British abandoned their idiosyncratic units of measurement decades ago.