Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

A recent EdSource podcast asks: “Why do so many students struggle to learn to read?” An equally essential question is: Why were so many struggling readers improving before the pandemic?

The possibility that reading has improved after third grade runs counter to conventional wisdom. Jill Barshay of the Hechinger Report writes “America’s reading scores were dropping before the pandemic.” Natalie Wexler, in The Atlantic, said, “students haven’t gotten better at reading in 20 years.”

These views are accurate when we compare the achievement of one year’s fourth grade students to a previous year’s fourth graders. But when we follow the same groups of students over time as they move through school, a much different story of steady progress emerges.

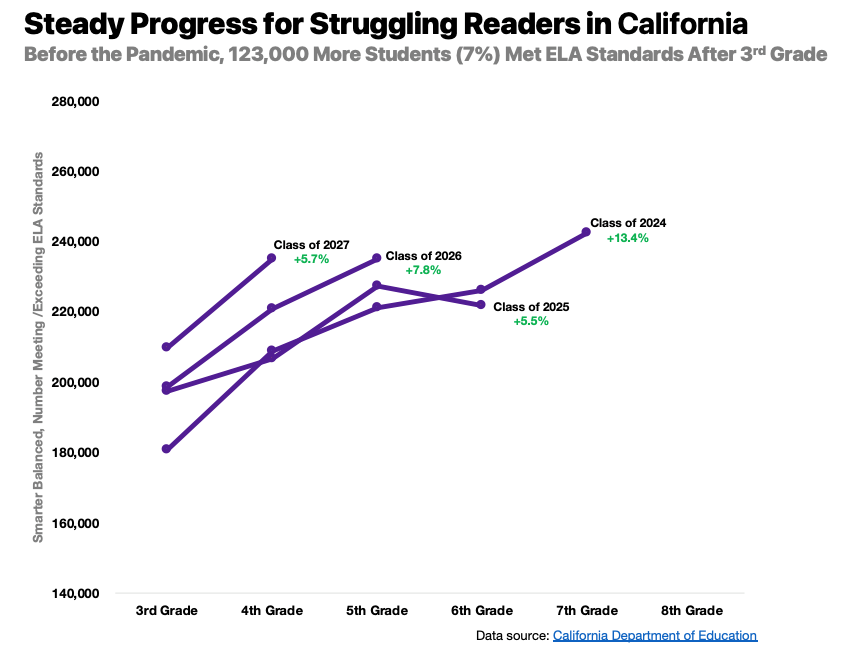

Grouping third graders by when their class will eventually graduate from high school in California (e.g., third graders in 2015 would graduate in 2024), we can see that in four classes before the pandemic, English Language Arts (ELA) achievement grew as they moved through school.

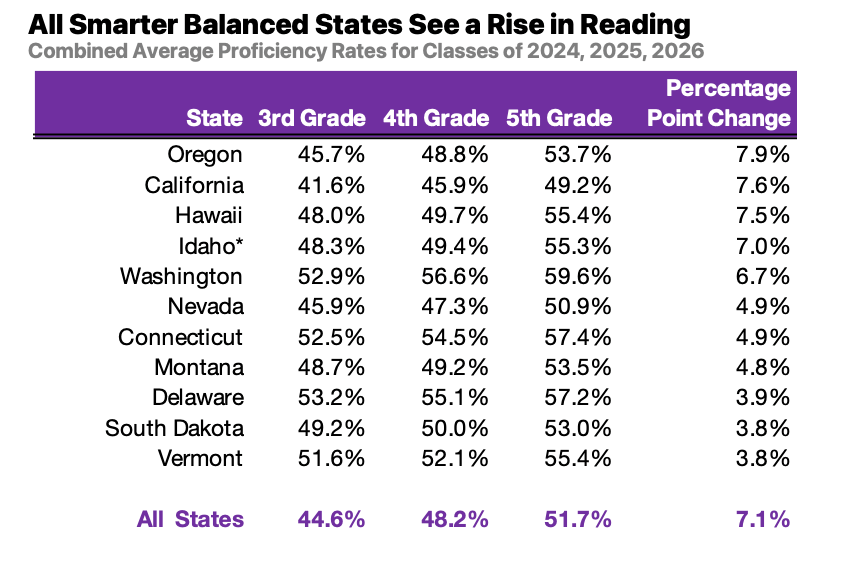

After failing to meet English language arts, or ELA, standards in the third grade, 220,000 elementary and middle school students in California, from the classes of 2020-2028, grew to meet the state standards in later grades. These gains in reading and writing are not limited to California but are visible in all the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium states. California ranks second, with a 7.6% growth in the percent proficient for the three classes below:

The gains can also be seen on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, when we look at percentages of students scoring at Basic & Above. However, they are limited to literacy and are not seen in mathematics. More data can be found in our report, The Rise in Reading.

Some of the leading districts — San Diego and Garden Grove — are familiar in reform circles. But others with double-digit gains over time, such as San Jose, Riverside, Visalia, and Oak Grove, are not.

Because the state hasn’t been following the same groups of students over time, no one saw the progress. As a result, no one was learning from it either. It’s time to understand why struggling readers improve.

We don’t already know the answers. A wide array of resources and research offers teachers guidance on what to do for struggling readers. But there isn’t any report or book that looks back at those who have improved, to ask how and why. Such inquiries are common in medicine and epidemiology but rare in education.

Three hypotheses are worth exploring:

First, many districts now give screening and diagnostic tests two to three times a year that pinpoint students’ reading strengths and weaknesses. In turn, these results are used to plan instruction and identify appropriate interventions.

Not all struggling readers need help in all areas of reading. It may be that some schools and districts are targeting support more efficiently. Students who need help with decoding get it, while those who primarily need help with fluency or comprehension don’t waste their time in “balanced” interventions. Better alignment of diagnosed ailments and remedies might be contributing to growth.

Second, better curricula and instruction might be making a positive difference. Groups like the California Curriculum Collaborative are helping districts select new materials that emphasize foundational reading skills, knowledge building and support for English language learners. At the same time, the National Council of Teacher Quality reports considerably more teachers are being trained in reading comprehension methods than were a decade ago.

Finally, it’s worth inquiring how changes in student motivation and effort may have contributed to the growth. There are interventions with a track record of ensuring students encounter reading experiences in which they can build their self-efficacy. Motivation and effort could have improved if students had more choice, as well as chances to read relevant and thematically engaging texts.

Now is the time for reading coaches and expert teachers in the leading districts to truly understand why struggling readers have improved in California. At the same time, the state is nowhere near where it ought to be.

There are still not enough early learning opportunities for families of color and families facing poverty. The lack of research-based reading instruction means many districts don’t prevent reading difficulties before they happen. The injustices and obstacles keeping many students from reading and writing on grade level have only grown during the COVID pandemic.

As schools and districts continue to recover from the pandemic, we must answer both questions. We have an opportunity to learn from our past successes and use this knowledge to accelerate future progress.

•••

David Scarlett Wakelyn is a consultant at Union Square Learning, a nonprofit that works with school districts and charter schools to improve instruction. He previously was on the team at the National Governors Association that developed Common Core State Standards.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

SD Parent 2 years ago2 years ago

I agree with the premise to find best practices to improve the outcomes for struggling readers. But it's a sad commentary when the focus is on the 5.5-13.4 percentage point increase in the number of students have improved over two to five years and finally met ELA standards than the overall 49% of California students did not meet ELA standards before the pandemic (in 2018-19). This figure includes the 43% of 11th graders … Read More

I agree with the premise to find best practices to improve the outcomes for struggling readers. But it’s a sad commentary when the focus is on the 5.5-13.4 percentage point increase in the number of students have improved over two to five years and finally met ELA standards than the overall 49% of California students did not meet ELA standards before the pandemic (in 2018-19). This figure includes the 43% of 11th graders who were nearing graduation (in 2020) but still didn’t meet ELA standards.

Elizabeth Silva 2 years ago2 years ago

Read this article in the Wall Street Journal about the shocking gains made simply by reading aloud quality literature to kids: Reading Aloud Can Remedy Covid Learning Loss: While listening to stories children develop a deeper understanding of language and other subjects, by Megan Cox Garden, September 16, 2022