Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

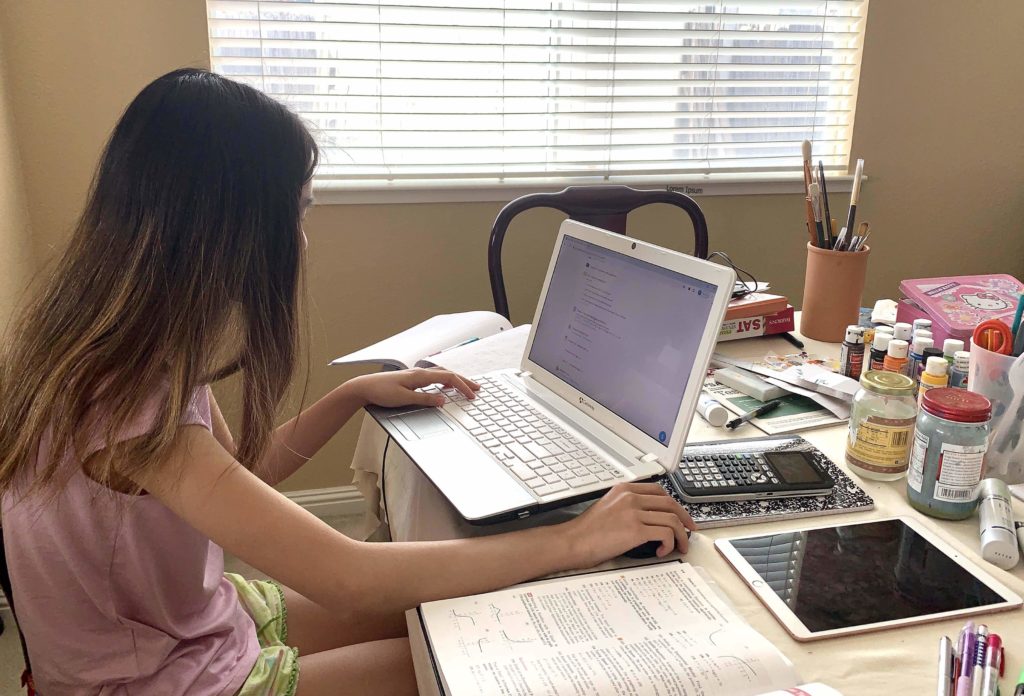

As California schools hurry to implement distance learning plans for students at home during the coronavirus pandemic, many are facing new questions about how to protect student data privacy as they shift to online education. Here’s what parents, educators and students need to know:

What privacy laws apply to California students?

In 2014, California passed the Student Online Personal Information Protection Act, which prohibits companies providing online services for K-12 schools and students from selling student data or using that information to advertise to students. It also requires that companies delete student data if a school or district requests it.

That law aligned with federal student privacy laws, including the Children’s Online Privacy Act, which applies to online businesses that sell products or services for children. Enacted in 1998, the law requires a website or mobile app to obtain parental consent before it can collect personal information about children under 13. It also requires the site or app to disclose their data collection practices, such as in an online privacy policy.

The new California Consumer Privacy Act applies to data collected by non-education apps that teachers might use during the pandemic, such as Zoom. The law extends requirements for collecting, selling and deleting personal information to companies providing all types of services — not just those that are aimed at children. It also requires those companies to obtain a parent’s permission before selling personal data of a child under 13. Teens between the ages of 13 and 16 can give consent themselves.

The new consumer privacy act lists education records, as defined under the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, as personal information and gives students over 16 in high school and college the right to opt out of the sale of their data.

Can teachers use video with students if teaching remotely?

Yes — but be careful. There generally aren’t privacy issues with a teacher giving a video lesson. And it can be comforting for some students and easier to learn from a familiar face on screen rather than a recorded voice or worksheet.

But schools can run into problems if teachers or students record or snap photos of the virtual classroom.

“Think back to when you were in high school and imagine the most embarrassing thing that happened to you in a classroom,” said Bill Fitzgerald, a Consumer Reports privacy researcher. “Now imagine a recording of that being made and shared in a format that potentially ensures it will live there forever.”

A safe alternative is for teachers to stick to a lecture or short video lessons and don’t record the parts that involve students if possible, said Amelia Vance, director of education privacy at the Future of Privacy Forum, a nonprofit think tank that focuses on data privacy.

Fitzgerald suggests strategies like student-led research or one-on-one check-ins with a teacher and student that don’t require a class to attend a video meeting.

Can teachers share photos of virtual classes online?

No, Vance said. Photos of students, as well as their names, which often appear on their video in a video conference platform, are personal information and privacy laws apply, she said.

How do teachers prevent inappropriate screen shares or Zoombombing?

One of the simplest ways to avoid unwanted video guests or screen shares, now commonly referred to as Zoombombing, is by using the security settings that are available to those who are hosts in a meeting. Those settings include who can determine who has access to the meeting and who can control the screen.

To keep uninvited attendees out, teachers can check to see if their video service allows for password-protected meetings so others can’t join in if they find (or guess) the meeting ID number. Zoom recently updated its video settings to require a password by default to enter a meeting. The password settings are locked for free K-12 education Zoom accounts and cannot be turned off.

Another important tip: Schools should set expectations early, such as making it clear that using a cell phone to take a video of an in-class video session is a violation of school policy.

How can I check if the tools being used by a school will protect students’ data privacy?

Teachers should try to stick to education technology products that districts have vetted for privacy already, Vance said. If that’s not possible, companies that collect personally identifiable information — such as email addresses, Social Security numbers, or education records — must have a public-facing privacy policy that users can review.

When using tools like Zoom, teachers should avoid creating consumer accounts and instead open an education account, which has a different privacy policy for student data. Zoom handles personal data of K-12 school accounts differently than basic accounts, but says both privacy policies are compliant with privacy laws.

“Educators who sign up separately from the education product are subjecting themselves and the students to the normal policy,” Vance said. “A lot of virtual classrooms are being created where we don’t know how the data is being shared or sold or other things that are highly regulated under student privacy laws.”

Common Sense Media also publishes free reviews of education and children’s apps with ratings on how well a company’s privacy policy aligns with federal and state student data privacy laws, as well as how transparent and strong the policy is.

The California County Superintendents Educational Services Association has created a sample checklist and other guidance for school districts on complying with the student online privacy laws.

How can parents ask companies to delete or stop selling their child’s data?

In California, companies are required to offer at least two ways for consumers to request to know what data companies collect about them, ask for it to be deleted and opt out of the sale of their data for users over 16. Options might include a “Do Not Sell My Info” link on a business’ website, a toll-free number or a direct email address.

Common Sense Media has forms for parents and consumers to ask companies to stop selling their or their children’s data.

If a third-party education company stores student data in the cloud, parents should contact the school or district to make a request to the vendor to delete student data.

What are some limitations in California’s privacy laws?

While compliance with privacy policies is important, Fitzgerald said it’s “the lowest bar” to ensuring students have a safe and meaningful learning experience. “A company can be fully compliant and still not do great things with data,” such as collecting and storing non-essential information about users.

Another issue is simply raising awareness of the rights that California parents and students have regarding their data. Some may not know it is up to a user to request that their information be deleted or to request their data to stop being sold if the user is over 16. Another issue is that opting out can be a burden, as most students and families use a number of different apps and digital tools they would have to contact individually.

“The privacy concerns are real,” Fitzgerald said. “But they are embedded in a larger series of questions of what we want school to be and what we want learning to look like and how we care for students in a time that’s difficult.”

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Sue Digre 4 years ago4 years ago

2020 is there still a list of low performing schools in Calif?

What law allows parents to request a transfer to a performing school district ?

Replies

John Fensterwald 4 years ago4 years ago

Sue, good questions. Here is the list of schools on the low performance list, as required by the Every Student Succeeds Act; you will be looking for those receiving Comprehensive Support and Intervention (CSI). Because of school closures, I believe the school list is a repeat of the year before. https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/sw/t1/essaassistdatafiles.asp State law no longer enables a parent in the list of low-performing schools to request a transfer to a better performing school in another district. … Read More

Sue, good questions.

Here is the list of schools on the low performance list, as required by the Every Student Succeeds Act; you will be looking for those receiving Comprehensive Support and Intervention (CSI). Because of school closures, I believe the school list is a repeat of the year before.

https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/sw/t1/essaassistdatafiles.asp

State law no longer enables a parent in the list of low-performing schools to request a transfer to a better performing school in another district. That right ended when the Every Student Succeeds Act replaced the No Child Left Behind law. The criteria for making the list changed significantly.

You are correct that the school choice program that was part of NCLB and is not part of ESSA. The link below provides language on that.

You can find an explanation on this state website:

https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/sw/t1/schoolchoice.asp#:~:text=The%20public%20school%20choice%20(Choice,the%20implementation%20of%20the%20ESSA.&text=However%2C%20LEAs%20must%20allow%20such,grade%20level%20in%20that%20school.