Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

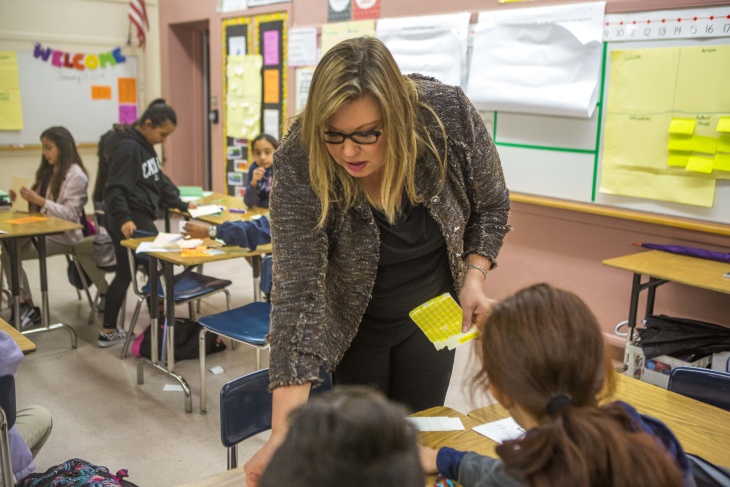

Science teacher Michelle Levin has only 33 kids in each of her classes — which makes her fortunate.

That’s not because a class of 33 is “small.” Levin’s class sizes at Daniel Webster Middle School in West Los Angeles are larger than national averages for similar middle schools, which range from 26 to 28 students.

But Levin says 33 students is small by L.A. Unified School District standards. In most LAUSD middle schools, the largest core classes have 37 kids — and can sometimes be as large as 46.

“We’re at the whim of the district for class size,” said Levin as she picketed on the first day of her union’s strike against LAUSD.

“For me, that’s the number one reason I’m out here, because it’s not fair to have so many kids in a class.”

Throughout a protracted contract fight with the school district, leaders of United Teachers Los Angeles have demanded a complete rewrite of the district’s class size rules, aiming to make current classes smaller and give the district less power to make them bigger.

To Levin, the benefits are clear: a smaller class size means each student gets more than her fleeting attention. It means she can actually return parents’ phone calls. It means 150 papers to grade each night, not 200.

“Class size is a fundamental issue,” the union’s president Alex Caputo-Pearl said at a recent press conference. “That is about student learning conditions. That is about educator working conditions.”

LAUSD officials have proposed reducing class sizes from current levels by a handful of students in certain schools, subjects and grade levels.

Still, class size reduction requires hiring more teachers, which is costly. While LAUSD officials say they wish they could reduce class sizes even further, they also say they’re running out of money to spend on the union’s demands. (UTLA leaders dispute this claim, saying they think the district is hiding money.)

Photos by Kyle Stokes/KPCC

Michelle Levin, a teacher at Daniel Webster Middle School in Los Angeles, says she teaches 33 students per class — which is low for L.A. Unified School District standards. On the first day of the teachers strike, Levin walked the picket line outside the school where she teaches. (Photo by Kyle Stokes/KPCC)

But if the district could scare up more money, is class-size reduction the best way to spend it?

There are studies, if few and far-between, to support parents’ and teachers’ intuition — that smaller classes are better for kids. But researchers disagree whether the high price of even a marginal reduction in class size produces enough benefits to be worth the high price tag, especially when it comes at the expense of another program that might help high-needs students.

“Reducing class size is one of the most expensive things you can do in education,” said Matthew Chingos, who runs Urban Institute’s Center on Education Data and Policy. “You always have to think about the intervention in the context of what it costs.”

One of the highest-quality studies on class sizes, Chingos said, came out of Tennessee in the 1980s. Students from kindergarten to third grade were sorted into small and large class sizes.

The study found students in the smaller classes — with an average of 15 students — scored markedly better on tests and were more likely to go to college than students placed in larger classes.

But the “larger” classes in that study were bigger by one-third, with 22 students.

Compare the class size numbers in that study with the reductions on offer in LAUSD-UTLA negotiations. School district officials propose spending $130 million to reduce some classes sizes — but only by a few students, not by one-third. Here’s what the district proposes:

Neither side has proposed reductions in classes that are already small. Most neighborhood schools’ smallest classes would continue to be capped at 27 students. Magnet schools’ smallest classes would still be capped at 24.

In other words: LAUSD is spending millions to make only marginal reductions in class sizes. Chingos said it isn’t clear that these slightly smaller class sizes will result in material benefits to students — especially if they come at the cost of some other program.

“If you had an extra $1,000 per kid to spend,” Chingos said, “it’s not clear that you would definitely want to spend it on smaller classes versus paying your teachers more, providing more money for textbooks, for a music program or after-school activities.”

By district estimates, the money LAUSD is currently devoting to a class-size reduction proposal could easily meet other union demands that LAUSD’s current offer only partially meets: a full-time nurse in every LAUSD school; a full-time librarian in every middle and high school; more counselors, deans and social workers.

But Bruce Baker, a professor at Rutgers University who’s studied education policy for two decades, takes a different stance: He says the research is more conclusive about the benefits of class-size reduction for kids than Chingos makes it sound.

Baker acknowledges the benefits should be weighed against the high cost of class-size reduction — but unlike Chingos, he doesn’t think there are that many ways to spend the money better.

“Class-size reduction is expensive,” he said, but “it is unclear that similar or greater gains can be achieved for measurably less.”

As much as LAUSD superintendent Austin Beutner says he’d like to reduce class sizes even more, he says the district doesn’t have the money for it. Beutner suggests United Teachers Los Angeles leaders might consider trading other contract demands for greater class-size reduction — if that is, in fact, their priority.

Noting that the district has offered a 6 percent salary increase to teachers, Beutner floated the idea of putting some of that wage hike toward greater reductions in class sizes.

“We’d entertain that notion,” Beutner said in an interview with KPCC/LAist. “If UTLA came to us and told us their members would take something other than [a] 6 [percent salary increase] in order to reduce class size … we’d listen.”

Union leaders would disagree with Beutner’s assertion that the district is out of money to spend. (Read more on that dispute here and here.)

But Baker says there’s another problem with framing the dispute as a trade-off between class sizes and wages: in L.A. Unified, class sizes and wages aren’t very good by relative standards. An LAUSD teacher could make between $10,000 and $20,000 more per year just by moving to neighboring Long Beach.

Baker says spending on either probably does the district good.

“We’re only going to be chipping at the edges on either,” Baker acknowledges, “and with class sizes that large … my gut tells me you’re probably better off chipping at those edges.”

UTLA leaders’ decision to make class-size reduction a centerpiece of negotiations has proven to be a shrewd organizing move, both in winning broad public support for the strike and in galvanizing the union’s rank-and-file.

At the bargaining table, though, the sticking point on class sizes is not only how much the district proposes to spend — but the authority it wields over the issue.

The teachers’ current contract includes an “escape valve” — a provision that gives LAUSD officials broad discretion to unilaterally raise class sizes in order to balance their budget.

UTLA leaders wants that safety valve closed off for good. If the district won’t agree to remove the provision, union leaders say they can’t trust that district leaders won’t just ignore any deal it cuts on class sizes later.

LAUSD officials have offered to remove this safety valve — but have insisted on replacing it with new language that also grants the district the power to raise class sizes under certain conditions. District officials say they need this flexibility in case of a fiscal emergency.

Here again, union leaders have objected. They’ve said the district’s proposed replacement language gives LAUSD even more power to raise class sizes than the original “escape valve” clause.

In other words, the union wants this section of the contract gone, full stop.

Beutner has said that’s not happening. He urged UTLA to come forward with a different counter-offer, but so far he hasn’t gotten one.

“We’ve gone as far as we think we can with the dollars we have,” Beutner said. “It’s time for [UTLA president] Alex [Caputo-Pearl] to tell us what he wants … He told us two years ago he wants … to create a crisis. Congratulations. He has one. Now what? What’s it going to take to solve it? Tell us all.”

For a moment, set aside the research; set aside the question of costs and regulations.

The ground truth is: parents want small class sizes.

There’s a classic L.A. School Board moment from a meeting in 2013, during a debate about class-size reduction, where then-board member Steve Zimmer issued a stark reminder that LAUSD has competition: charter schools, which are publicly funded but staffed with non-union teachers, counselors, and other personnel.

“Here are some websites of charter schools,” Zimmer said, holding up printouts. “And on the front pages of every website is class size — 20-to-1. 22-to-1…”

He started tossing a half-dozen printouts to the floor. His message was clear: other schools are using small class sizes as a selling point.

“You get to give more individualized attention … when there are less students in your classroom,” Zimmer, a former teacher, said. “And if you don’t believe that, and you don’t believe me … trust the choices that parents have made.”

Embedded in Zimmer’s argument was a warning: if LAUSD doesn’t offer smaller classes, parents will flee the district for schools that will — and not always schools with unionized teachers.

Zimmer had a point: L.A.’s charter school enrollments have skyrocketed in recent years, jeopardizing the district’s finances. Funding from the state is dictated by enrollment and attendance. And even though L.A. Unified is the second-largest school district in the country, its enrollment has been declining for more than a decade — leaving it with a smaller and smaller stream of funding.

With every student who leaves, that makes it much more difficult for the district to afford a lot of things parents want — including smaller class sizes.

This article is published courtesy of KPCC Radio.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (4)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

JudiAU 5 years ago5 years ago

Librarians should be in every school but are not. To my knowledge, no LAUSD school has an actual full-time librarian. The union requirement is an authorized “library assistant” who holds none of the skills listed below. There is zero reason a parent or teacher cannot be trained to check in and out books. Those books by the way? LAUSD hasn’t purchased books for the last 13 years.

Something is better than nothing.

Neutral Observer 5 years ago5 years ago

As a former librarian at a prestigious private university, I am appalled to see the comment from another librarian degrading the role of a school librarian to be merely “checking out a book” that “a monkey” can be trained to do. My librarian science training at UCLA did not include checking out books but instead learning how to spot needs, revitalize interest and create innovative services. Let me give an example of a dedicated, competent … Read More

As a former librarian at a prestigious private university, I am appalled to see the comment from another librarian degrading the role of a school librarian to be merely “checking out a book” that “a monkey” can be trained to do.

My librarian science training at UCLA did not include checking out books but instead learning how to spot needs, revitalize interest and create innovative services. Let me give an example of a dedicated, competent librarian that I have the good fortune to know at an inner city school in LAUSD. She created a partnership with the teachers, offering a way for students needing remedial help and opportunity to earn extra credits to pass their classes. These students come to the school library, where she would help them pick out reading materials suitable for their levels. With the librarian’s help, the students would write book reports which would be graded for the extra credits. This librarian was a former English teacher who went back to college for librarianship certification when she sensed a need in the school she was teaching. She carved a niche and became a part of the school’s success in turning around poor performance.

She couldn’t have done it alone without the love and support of fellow teachers and school administrators who are also very dedicated problem solvers. The school staff and administrators together took the school to go “pilot” and became a Cinderella story within LAUSD. My point is, if you care to look around, there are public schools that manage to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat, if given the right resources and flexibility.

If we see an under performing public school, the correct attitude is not starting with the assumption that public education is an incurable failure. I used to subscribe to the notion that public school teachers ask for too much and public schools are beyond help. As an MBA graduate in senior managerial role in the business world now, I have been told again and again that unions are always bad for business, creating costly and inflexible conditions. The more I got to know the current generation of LAUSD teachers and look into the nuances, the more I know at least with them this is not the case. From salary per work load standpoint, union teachers are doing more per dollar. An average union teacher’s salary is just under $64k while that of a charter school teacher is $55k in Los Angeles. However, a union teacher has a typical class size of 40+ students, twice the class size faced by a charter school teacher. Quantitatively this translates to twice as much homework for grading. This not even including the unquantifiable such as the challenge of maintaining a good flow for a large class, with many students coming from disadvantaged background. With easily twice the work, a union teacher isn’t getting twice the pay. $9k extra is it. As voters, let’s stop seeing public education as an easy target to attack and also let’s stop giving lip service to public educators when we tell them we care about our school kids. A well run charter school can benefit hundreds of kids. But a well run public school benefits thousands. Even a sub-section of LAUSD can have tens of thousands of kids deserving a chance to beat the odds.

Charter is here to stay, no doubt. But let’s not make charter school the single solution to all ills. There are public schools that have demonstrated turnaround abilities. Francis Poly High in Sun Valley is one of them. Let’s find out more schools like that, observe their methods and inspire schools in similar communities to do the same. Charter and non-charter public education cannot become a zero sum game.

JudiAU 5 years ago5 years ago

Our charter school is for the education of children not the protection of teachers and staff. The teachers at our charter school have pensions, heath care, and a grievance process. And a class size of 25 students. Their wish lists sell out instantly. They are showered with support. We have parent organized libraries, lunch help, etc because it is allowed. LAUSD doesn't have libraries because of the Union. You can teach a monkey to check … Read More

Our charter school is for the education of children not the protection of teachers and staff. The teachers at our charter school have pensions, heath care, and a grievance process. And a class size of 25 students. Their wish lists sell out instantly. They are showered with support. We have parent organized libraries, lunch help, etc because it is allowed.

LAUSD doesn’t have libraries because of the Union. You can teach a monkey to check out a book and I say that as a librarian. Parents can absolutely help. There are way, way to many non-classroom staff. Too much admin. Too many empty schools that need to be sold, land leased or sold. The three closest elementary schools near me are less than 1/3 enrollment. It is criminal they aren’t closed, students, reshuffled. All the schools have test scores that stink. The board has to take action to close schools, sell land, fire staff, get smaller, leaner, and smarter.

UTLA has the schools they created.

Our family has wrestled with returning to a district gifted program this year for our oldest. Our charter school is almost perfect but we wanted something more rigorous. We were so close. So I subscribed to a couple of PTA listservs and related communication. It isn’t worth it.

LaParent 5 years ago5 years ago

The LA school district will go bankrupt in 3 years if union's demands are met. The teacher makes average $75k and with great health benefits (life-long health care for the teacher and his family without little premium) and 3 months vacation, pension plan. And they still want more and demand less test or less accountability. That's just too greedy comparing to the hundreds of thousand working parents with little or no health insurance. Thinking about … Read More

The LA school district will go bankrupt in 3 years if union’s demands are met. The teacher makes average $75k and with great health benefits (life-long health care for the teacher and his family without little premium) and 3 months vacation, pension plan. And they still want more and demand less test or less accountability. That’s just too greedy comparing to the hundreds of thousand working parents with little or no health insurance. Thinking about thousand new graduates without a job or earning a minimum wage. I think we should raise the starting salary to attract more young people to teach in school! Here is an article about the financial fact about LAUSD.