Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Millions of adults in California have few skills, no college credentials and are stuck in low-paying jobs.

Gov. Jerry Brown says these “stranded workers” can learn the skills they need to get ahead at a new $240 million online community college that will be funded over seven years to provide courses tailor-made for the state’s employers.

It’s a legacy-making endeavor in his last year as governor that he and his supporters, including the chancellor of the community college system, Eloy Ortiz Oakley, have pushed hard to promote during this year’s budget season.

Establishing the college would be a dramatic expansion in online education aimed at a segment of the labor force that higher education has not traditionally served, the governor’s plan contends.

“This is a game changer for workers,” said Rebecca Miller, the political director of SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West, at a March legislative hearing about Brown’s proposal. Her members are “people who cannot get to the community colleges during the day, and even evenings and weekends,” she said.

The union, with its roughly 100,000 workers, expects the state will need to fill annually 65,000 allied health positions — non-physician jobs like medical assistant, MRI technician and billing coder — through 2024.

“That is exactly what I have been looking for, waiting for,” said Tracey McCreey, a licensed vocational nurse since 1998 who wants to earn a college degree as a registered nurse. “I have searched on the internet everywhere for opportunities for me to advance online, because of my schedule.”

The courses will be targeted to students who “are the individuals that are most vulnerable to the changes in the economy,” said Eloy Ortiz Oakley, chancellor of the community college system.

Brown’s proposal is designed to provide job-boosting academic training to the estimated 2.5 million Californians ages 25 to 34 who lack a college degree or certificate, half of whom are Latino, and also to older adults who similarly lack a college education.

Backers of Brown’s proposal say California requires a new blueprint for training the state’s under-educated adults. Oakley, several community college presidents and others argue the current selection of online courses at community colleges is largely designed for degree-seeking students — not what this financially strapped group of adults needs to get ahead.

Instead, these workers require courses that lead to jobs quickly and that aren’t dependent on the traditional academic calendars or hours of community colleges, the pro-online college camp argues. They “are the individuals that are most vulnerable to the changes in the economy,” said Oakley at the March 20 Assembly hearing.

Among other things, the online community college would focus on short-term, affordable credentials that are aligned with licenses, such as a food handler’s license, medical biller or entry-level management course to become a supervisor at an information technology firm, that signal to employers a worker is trained to do specific work. An employee could earn multiple certificates that stack on top of each other, demonstrating deeper knowledge. The college would also reward workers with college credit for the skills they picked up on the job through various demonstrations of skills, something known as competency-based learning.

Many details of the plan still need to be worked out, but Gov. Brown is eyeing training for popular job sectors like advanced manufacturing, healthcare and information technology, among others.

A new report on the state’s 2.5 million “stranded workers” says that just over half work full time, and 45 percent are employed in retail, education, social and health services, and food services. Most earn relatively low wages: 58 percent earn less than $25,000, compared to 34 percent of workers in this age group who have degrees, according to California Competes.

The workers are spread across California and represent sizable portions of the state’s region. Fifteen to 29 percent of the state’s 25- to 34-year-olds are stranded workers, depending on the region. The concentrations are higher in rural areas such as the northernmost part of the state and the San Joaquin Valley.

But a bevy of lawmakers, educators and analysts are skeptical of Brown’s plan.

Some state legislators wonder why money for the online college can’t go toward the online programs already in existence across the 114-campus California Community College system. For them — whose support the governor needs for this plan to pass — the issue isn’t whether online education is necessary, but whether the state needs a new online college to address the state’s workforce needs.

“I am much more skeptical now than I was when I first heard it,” said Assemblyman Jose Medina, who chairs the Assembly Higher Education Committee during a March 20 hearing. The plan “doesn’t show me that it has been thoroughly thought out, at all,” he said.

“This is taking something that is an idea and just putting it forward and asking the Legislature on faith to approve it.”

Other legislators also worry the online college would divert resources from the rest of the system. Several faculty unions oppose the college and claim there are no assurances that the college’s faculty will join the faculty union. Oakley responded during a March 20 hearing promising that the college “would absolutely be a collective bargaining college.”

The independent Legislative Analyst’s Office is not convinced that “stranded workers” have trouble accessing community college. There is “no information that gives a sense that there is a specific problem with access that is being solved by the online community college,” said Edgar Cabral, an analyst of community colleges at the Legislative Analyst’s Office, during a March 20 Assembly subcommittee hearing on the governor’s proposal.

Part of the frustration over the proposal is the paucity of specifics. “There’s very little meat on the bones right now,” said Asm. Richard Bloom (D-Santa Monica) at the hearing.

But even without the nursing degree, there are numerous short courses McCreey, 48, said could benefit her or her colleagues. Training on cultural differences in patient care. A recap on phlebotomy, the act of drawing blood. A doses calculation course, something “that’s really important when people are looking to upgrade from a medical assistant to a LVN (licensed vocational nurse) — that is a barrier because math is difficult.”

A Legislative Analyst’s Office report argued similarly, writing that if the goal is to expand online education or reward students with course credit for skills they’ve learned on the job, the state could incentivize the existing colleges to do just that.

However, the report noted current state funding rules make those changes difficult.

Case in point: While the community college system is piloting a program in which six colleges are sharing several dozen online courses, the college that created the course receives the state funding for enrollment, even if those students are primarily enrolled at another college. “This means colleges only have a fiscal incentive to participate in the exchange if they believe they can ‘win’ more students than they ‘lose,'” the analyst’s office report said.

Some lawmakers have said the Legislature could pass rules to allow the current system to experiment more. “If there’s existing statute, we can modify those,” said Sen. Richard Pan, D-Sacramento, at a Senate hearing in February.

Another kink is figuring out where students of the proposed online college will receive hands-on training. The governor’s plan said libraries, employer and labor groups, and other community colleges are possibilities. “Without partnerships in all areas of the state, students may not have access to hands‑on experiences critical to program completion,” the analyst’s office report said. Oakley has told lawmakers his office is working to create those partnerships.

But Rebecca Hanson, executive director of the joint education program between unions like the SEIU-United Healthcare Workers West and health sector employers, said that the anticipated growth in new positions means workers will need clear pathways to advance their skills, something that’s not available to many health workers. Entry-level workers, such as medical assistants, may struggle to find the academic training that allows them to move up to more lucrative positions like medical coders — workers who identify the procedures a medical office provided so that insurance companies pay them fairly.

She also cited an internal survey that showed more workers she represents prefer to take continuing education courses online than in person.

In recent years community college students have expressed an appetite for more online coursework. In 2016-17, 13 percent of California’s community college courses were online. And while the pass rates are higher at in-person classes than online classes, the gap has been closing the past decade — 72 percent for in-person classes to 65 percent for online classes.

Pushing back on concerns that the online college may cannibalize enrollment at other community colleges, Thomas Greene, president of American River College, a community college in Sacramento, said at the March 20 hearing that the proposed online college instead “may complement” other colleges, mirroring a point Oakley made that the online college may create a larger population interested in furthering their postsecondary training.

Credit: Wadi Lissa on Unsplash

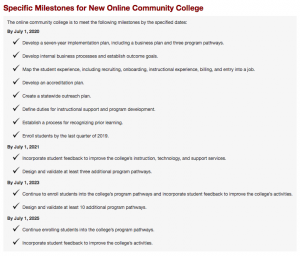

Click on image to expand timeline of key milestones for the online community college, should it pass.

The $240 million cost is spread out over seven years. Initially the college will use its $100 million in start-up funding to begin the work of developing academic content, marketing itself to students and purchasing the equipment needed to get off the ground, among other expenses. The plan also allocates $20 million each year for faculty salaries and technology maintenance. Once the college begins enrolling students some time after the summer of 2019, the college will also receive state apportionment money based on how many students they teach — similar to the way other community colleges in California are funded now.

It’s unclear how much students will be charged for the proposed college. Because it would offer classes year-round and be tied to employer demands, the college wouldn’t necessarily follow the standard $46-a-unit cost the system’s current colleges do. Still, Oakley said that the college’s students would be eligible for state financial aid and that the cost of attendance will be low.

Students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid or to transfer their credits to other community colleges until at least July of 2020, when the college expects to come up with a plan to become accredited.

The Legislature has until June 15 to approve the plan as part of the state’s budget process. Both the Assembly and the Senate typically pass their budget bills by late May and agree on a compromise before the June 15 deadline.

Whichever direction the Legislature goes, McCreey is ready for an online college experience that fits her needs. “I have a son in college, my other three children are in a college-prep academy, and I think persevering and getting up and letting them see me do my homework late at night, early in the morning — whatever it’s going to take — I think that’s the motivation right there.”

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Bill 6 years ago6 years ago

It may be great. For making the argument, the examples here are not super compelling, though. Not sure where Tracey McCreey has been looking; I looked for about 5 minutes and found a list of 200 online nursing schools in California, most offering the degree AS needed to test for RN (www.nursing.org) and she needs a degree granting institute for her RN goal - if the CA Online CC system is targeting vocational certificates- it won't … Read More

It may be great. For making the argument, the examples here are not super compelling, though.

Not sure where Tracey McCreey has been looking; I looked for about 5 minutes and found a list of 200 online nursing schools in California, most offering the degree AS needed to test for RN (www.nursing.org) and she needs a degree granting institute for her RN goal – if the CA Online CC system is targeting vocational certificates- it won’t be what she is looking for anyhow.

That said, it is probably just what tons of people are looking for, just not the guy taking the carpentry class in Oakland that was used as a cover image for this article: i.e. clearly he is in a practical workshop classroom, which you cannot get online … or maybe that is the point?

Muvaffak GOZAYDIN 6 years ago6 years ago

I was a Californian from 1962 to 1970 at Caltech, Stanford and Hewlett Packard. I have been feeling indebted to USA and California for whole my life of last 48 years. Thanks for the education California provided to me. Here is my solution to Governor Brown: 1. Ask Berkeley " what vocations are needed in California , numbers and skills." Let them do a research. 2. Find people in the USA and in the world who are … Read More

I was a Californian from 1962 to 1970 at Caltech, Stanford and Hewlett Packard. I have been feeling indebted to USA and California for whole my life of last 48 years. Thanks for the education California provided to me.

Here is my solution to Governor Brown:

1. Ask Berkeley ” what vocations are needed in California , numbers and skills.” Let them do a research.

2. Find people in the USA and in the world who are best practicing these vocations?

This is important. You have to know the vocation itself very well before you teach it to someone else .

3. Get together these talented scientists at MIT and Stanford and Berkeley. Get them to develop online courses for you. They can do an excellent job at very low cost. Roughly $50,000 per course of 10 weeks, development cost. May be even less. 5,000 online vocational courses at $ 50,000 each. Total $250 million. You do not spend all at once . In 5 years say, ask edx, Dr Agarwal of MIT to transmit all these courses from internet. Cost is only $ 1 per person per course per year .

4. Get 40-50 managers from existing CC managers, I mean managers, not educators, to manage the system . Close rest of the 113 community colleges in 10 years.

I am retired now but investigating online for the last 25 years. See my own internet university open to 8 billion people in the world and free . http://www.worlduniversity.london.

If I have done it, Governor Brown can do 1,000 times better.