Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

A year-long battle between a coalition of school organizations and the California Teachers Association over district reserves has taken a new turn.

The dispute is over how much districts should be allowed to keep in reserve as a result of new limits that were set last year. The reserve cap became law after the CTA persuaded legislative leaders and Gov. Jerry Brown to insert the change into cleanup language as part of last year’s state budget negotiations.

The CTA had complained that districts were hoarding a bonanza of post-recession funding that it argued should be spent on student programs and services. Groups including the California School Boards Association, Association of California School Administrators, the California Association of School Business Officers, the California State PTA and the League of Women Voters countered that the new reserve cap was fiscally irresponsible, even though it likely is years away from taking effect. They claim it is a ploy to force more money saved for emergencies onto the bargaining table for potential pay raises and benefits.

But having failed to persuade the Legislature to repeal the cap, the groups, led by the school boards association, have proposed a late-session compromise to loosen the restrictions and fully exempt the state’s smallest districts.

Senate Bill 799, which the school boards association wrote, would raise the limit on a district’s unrestricted budget reserve to 17 percent of its general fund, in those years when a reserves cap is imposed. That’s nearly triple the 6 percent reserve under current law for most large and moderately sized districts. The new limit would not apply to money that districts have set aside for specific purposes.

The exemption would remove the cap entirely for districts with fewer than 2,501 students and the 10 percent of property-wealthy districts, known as “basic aid” districts, that are funded primarily through local property taxes, not state revenues. Together, small and basic aid districts comprise nearly two-thirds of all districts, according to the school boards association.

“We believe this bill is a good compromise and a solution that both houses of the Legislature and the governor can support,” said Dennis Meyers, assistant executive director, governmental relations, for the school boards association.

In a video statement, Molly McGee Hewitt, executive director of the business officers association, said, “We believe repeal is not a political reality even though (the cap) is not sound public policy. This is a chance to modify and change the reserve cap and to give back for our school districts some stability that we have lost.”

Even if the cap won’t be triggered for several years, the school boards association and other groups want it changed now. They view it as an intrusion on the principle of local control.

The school boards association made repealing the cap its top legislative priority for the year. But in May, Democrats who formed the majority in the Assembly Education Committee defeated repeal legislation sponsored by Assemblywoman Catharine Baker, R-Danville. Republican Sen. Jean Fuller, R-Bakersfield, withdrew her version of the bill from the Senate Education Committee.

Prospects for SB 799, with less than two weeks before the Legislature adjourns for the year, remain uncertain. Two Senate Democrats, Jerry Hill, D-San Mateo, and freshman Steve Glazer, D-Orinda, are the prime authors, with 15 Republican and Democratic legislators as co-authors. But the bill is stuck for now in the Assembly Rules Committee, which could send it either to the Assembly Education Committee for review or directly to the Assembly floor for a vote.

A spokesperson for the CTA said, without elaborating, that the union opposes the bill.

Districts currently have no limit on the size of their reserves, which are funds left over at the end of a year. They can use the reserve as a stockpile for emergencies and downturns in state revenue or as a set-aside for future purchases, such as technology or building repairs.

Democrats supporting the current law, led by Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell, a former teacher who chairs the Assembly Education Committee, said that the school boards association and others are exaggerating the risks of the budget cap.

Under current law, the cap on district reserves would go into effect only in a year after the state puts any money into a special rainy day fund for K-12 schools and community colleges. Those years, tied to tight revenue requirements under Proposition 98 and other conditions, would be rare – and probably not in the next three years at the earliest, the Legislative Analyst’s Office predicted in May. Districts could apply to county offices of education for an exemption.

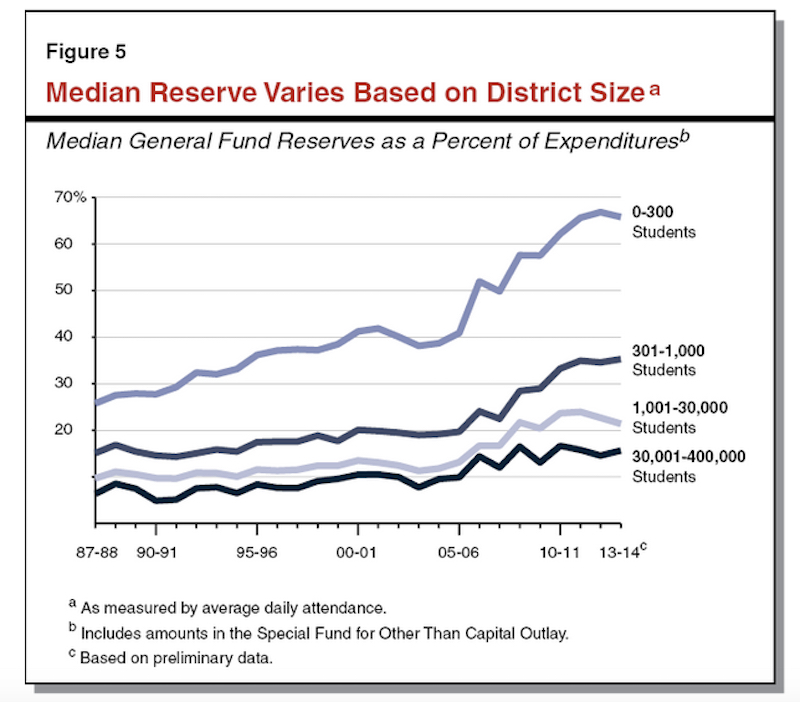

Credit: Legislative Analyst's Office

Districts substantially increased their reserves as a protection from budget cuts after the recession. The size of the reserves varied widely, with the smallest districts building the largest reserves. The median reserve for large districts – those with more than 30,000 students – was under 20 percent in 2013-14. The proposed limit for SB 799 would be 17 percent for money not designated for specific purposes.

Depending on a district’s size, the cap would range from 3 percent of a district’s general budget for the state’s largest district, Los Angeles Unified, to 10 percent for the smallest districts, with 6 percent the average for moderately sized districts.

Even if the cap won’t be triggered for several years, the school boards association and other groups want it changed now. They view it as an intrusion on the principle of local control that Gov. Brown espoused and the Legislature adopted with the Local Control Funding Formula. And they said the low cap could jeopardize their financial stability in an economic downturn, make it harder to manage their cash and cause bond rating agencies like Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s to lower districts’ credit ratings, raising the cost of borrowing money.

An LAO analysis earlier this year of 2013-14 found that, had the cap been in effect then, less than 10 percent of the state’s districts would have met the reserve requirements. Districts had $7.3 billion in unrestricted reserves, while the law would have set a limit of $2.8 billion.

Democrats supporting the current law, led by Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell, a former teacher who chairs the Assembly Education Committee, said that the school boards association and others are exaggerating the risks. The law already permits school boards to vote to shift money for specific future uses into what’s called a “committed reserve” that doesn’t count toward the cap. And that’s what districts would do to bring the unrestricted reserves down if the cap went into effect, they predict.

But Meyers called this option an unnecessary work-around, adding complexity to a bad law. SB 799 instead would require school boards to present annually an explanation of what’s in the reserves and justify the uses – a better form of transparency, he said.Hill and the school boards association chose 17 percent as the limit because that’s the amount that the Government Finance Officers Association, a national organization, recommends that local districts keep in reserve, with more money in times of volatile revenue. That amount equals between two and three months of a district’s operating expenses, said LAO analyst Kenneth Kapphahn, who wrote the LAO analysis. The LAO found that the median reserve for large districts with the strongest bond ratings was 17 percent.

Sen. Bob Huff, R-Diamond Bar, who stepped down this week as Senate minority leader, said that Republicans favor repeal of the cap, which he called a “dumb” policy, but would support SB 799 as written. However, noting that the finance officers recommended 17 percent as a minimum reserve, not as a limit, he said he was concerned that the number would be whittled down in negotiations over the bill.

Gov. Brown has not indicated whether he would support revising the reserves cap that he agreed to insert in the budget language a year ago.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (23)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Gregg Solkovits 9 years ago9 years ago

What kind of compromise is this? A triple increase in the "cap" and total exemption for small districts? SHAME on the PTA for playing along on this...for years districts have consistently robbed students and the classroom of needed resources by creating HUGE reserves for "fiscal emergencies"...yet there is ALWAYS money for out of classroom expenditures and consultants... IF those who want to let districts squirrel away too much money are serious about a compromise, … Read More

What kind of compromise is this? A triple increase in the “cap” and total exemption for small districts? SHAME on the PTA for playing along on this…for years districts have consistently robbed students and the classroom of needed resources by creating HUGE reserves for “fiscal emergencies”…yet there is ALWAYS money for out of classroom expenditures and consultants…

IF those who want to let districts squirrel away too much money are serious about a compromise, they need to show it by floating REAL compromise language

Replies

Tom 9 years ago9 years ago

Gregg – don’t get too excited – it is still only a 17 percent reserve which is really not a HUGE reserve especially for small districts.

Jennifer Bestor 9 years ago9 years ago

If there is any SHAME here, it is on the CTA! Maintaining this nonsense law will restrict spending on new and existing teachers. Think about it for one second! If districts are forced to spend down $6B of reserves the minute the state saves a nickel, the LAST thing they will do is commit to ongoing fixed costs. Hiring a new teacher or increasing salaries is a fixed ongoing commitment. … Read More

If there is any SHAME here, it is on the CTA! Maintaining this nonsense law will restrict spending on new and existing teachers.

Think about it for one second! If districts are forced to spend down $6B of reserves the minute the state saves a nickel, the LAST thing they will do is commit to ongoing fixed costs. Hiring a new teacher or increasing salaries is a fixed ongoing commitment.

(If YOU were forced to cut your savings to three weeks of expenses, would you buy a new home with a larger mortgage? No way. You’d spend the money on something that would make no future demands on your now-uncertain purse.)

el 9 years ago9 years ago

Rats, I meant the reply I made that ended up under Paul to go here to Gregg. What the crisis from 2008-2014 showed was that districts cannot count on the state to send money in times of trouble. Indeed, it didn't even send all the money it said it was sending, in that many districts had to borrow against their promised revenues. The LAO report is very very good and I highly recommend reading it closely. Reserves are … Read More

Rats, I meant the reply I made that ended up under Paul to go here to Gregg.

What the crisis from 2008-2014 showed was that districts cannot count on the state to send money in times of trouble. Indeed, it didn’t even send all the money it said it was sending, in that many districts had to borrow against their promised revenues.

The LAO report is very very good and I highly recommend reading it closely.

Reserves are going down as volatility from the state is going down. It’s rational to have reserves at least as large as one payroll. The LAO compared reserves across districts and to other government agencies, and interviewed districts to ask them about their reserve policy. Districts generally had good reasons for having those reserves relating to cash flow and uncertainty.

Paul 9 years ago9 years ago

People assume "salaries and benefits" means raises. Instead, what we're talking about here is (re)hiring teachers, to reverse drastic class size increases and revive canceled programs. Districts never spent down their reserves during the recession, even though they insist that that is the purpose of keeping reserves. Instead of trying to maintain services, they slashed positions and allowed class sizes to jump. The federal economic stimulus contained a maintenance-of-effort requirement that was completely ignored. During the three … Read More

People assume “salaries and benefits” means raises. Instead, what we’re talking about here is (re)hiring teachers, to reverse drastic class size increases and revive canceled programs.

Districts never spent down their reserves during the recession, even though they insist that that is the purpose of keeping reserves.

Instead of trying to maintain services, they slashed positions and allowed class sizes to jump. The federal economic stimulus contained a maintenance-of-effort requirement that was completely ignored. During the three worst years of the economic crisis, districts paid part of their (rapidly decling) bills with temporary federal dollars, stashing the regular revenue in reserve. The ARRA was meant to fund jobs that would not otherwise have existed, not to back-fill an existing payroll, let alone one that was being slashed through annual layoffs.

Revenue allocated for education should be spent in the year allocated. Tight-fisted districts should be ashamed of themselves for still not restoring teaching positions and services.

If the state wanted a true, general-purpose reserve, local school districts would be the last place to keep it. A former school principal promoted to assistant superintendent of finance on the basis of an administrative credential is not competent to manage a large public investment portfolio.

Replies

FloydThursby1941 9 years ago9 years ago

You have to be very, very careful with this and I think some money should be saved. Teacher salaries should go up but in return for agreements to make it easier to fire bad teachers and with fewer days off with subs, merit pay, etc. Here's why we should be afraid. 1. A recession could get worse and be scary, so reserves should be there unless we know we're coming back. 2. The … Read More

You have to be very, very careful with this and I think some money should be saved. Teacher salaries should go up but in return for agreements to make it easier to fire bad teachers and with fewer days off with subs, merit pay, etc. Here’s why we should be afraid.

1. A recession could get worse and be scary, so reserves should be there unless we know we’re coming back.

2. The statement that spending helps isn’t always true. Spending in NYC, Baltimore and DC is double San Francisco, and kids do worse. It’s not poverty, it’s motivation. Free and reduced lunch Asian kids in California and Asian and white in San Francisco do better on tests than not free and reduced lunch Latino and African American kids. Teachers need to do more to motivate these kids, poor kids and middle class kids of all races. One condition to a raise in my view should be to STOP BLAMING POVERTY AS A UNIVERSAL BOGEYMAN! If poor Asians do better than non-poor Latinos and blacks, focus on that, if Asians study triple what whites, blacks and Latinos do, focus on that, if teachers can get parents and kids to change this, problem solved, even if many kids are still in poverty.

3. The union makes me less inclined to want to support pay raises when they automatically oppose reforms which focus on quality, testing, studying, tutoring, teacher quality and anything which makes a difference. Thoughtful criticism which takes into account factors on both sides, convenient and inconvenient, is respectable. However, the ignoring of any fact which is inconvenient and automatic type arguments against changing any LIFO statute or making it so they can fire bad teachers makes me less inclined. It’s too automatic. I admit poverty is a factor, just not as much of one as others argue. I admit when something is true. The other side doesn’t argue like someone who is looking into all aspects of education and trying to come up with the best, balanced approach to increase test scores and college graduation and college readiness and instead argues like a lawyer paid by the teacher’s union. As long as I see these unbalanced arguments by teachers on blogs, I won’t support this.

4. If we do see drastic pay increases, this needs to be credited. I could imagine pay going up by 25% and the rhetoric staying the same, hearing there’s no money for supplies, teachers are underpaid. Teachers are paid double SF rates in DC, Baltimore and NYC, cheaper cities, but I still read arguments they’re underpaid. I recently saw several letters to the editor complaining police and firemen can’t afford San Francisco and need low income housing. They start at 85k and average 120k at base and more including overtime. We can’t get teacher pay that high, but from these letters even if we did, it wouldn’t set aside that issue and let us focus on others, so it makes me pessimistic we can fix the issue and move on if I see if we doubled it, we’d still get letters to the editor saying it’s too low. I don’t believe teachers are 50% underpaid, and teachers in SF earn under half what cops do vs. over 70% in San Diego. We have to find a salary that will enable teachers to say this is OK,and I should have some loss in security in return, yes due process, but no arguing a multi-year process is “simply due process”. There are teachers now at Lowell who have missed 3 straight back to school nights. I wouldn’t support any pay increase before the union agrees to sanction these people with fines. It’s morally reprehensible for a teacher to miss back to school night.

Jennifer Bestor 9 years ago9 years ago

Pshaw. On Election Day 2012, individual district reserves were the ONLY protection for California students and teachers against a 2013-14 financial chasm. Even Gov. Brown didn't think Prop 30 would pass ONE WEEK before that election. If it hadn't, the only cushion between our schools and $6++ billion of budget cuts were those reserves. The state owed our schools over $9 billion in 2011-12 that it couldn't pay except out of … Read More

Pshaw. On Election Day 2012, individual district reserves were the ONLY protection for California students and teachers against a 2013-14 financial chasm. Even Gov. Brown didn’t think Prop 30 would pass ONE WEEK before that election. If it hadn’t, the only cushion between our schools and $6++ billion of budget cuts were those reserves. The state owed our schools over $9 billion in 2011-12 that it couldn’t pay except out of 2012-13 funding.

Those deferrals have FINALLY been paid back this year. If there are still drastic class size increases and canceled programs in your district, take a hard look at where LCFF allocates funds and the CalSTRS pension deal. Don’t blame reserves.

el 9 years ago9 years ago

I highly recommend reading the LAO report in full and in detail. Many districts spent down their reserves during the recession either in practice or on paper. By 'on paper' what I mean is that revenue during that time was intensely volatile - districts must adopt a budget that shows solvency three years out in June, during years when the Legislature hadn't committed any particular amount for schools, and at times when they were saying, … Read More

I highly recommend reading the LAO report in full and in detail.

Many districts spent down their reserves during the recession either in practice or on paper.

By ‘on paper’ what I mean is that revenue during that time was intensely volatile – districts must adopt a budget that shows solvency three years out in June, during years when the Legislature hadn’t committed any particular amount for schools, and at times when they were saying, “Oh, in January we’ll maybe cut $500/student, and probably eliminate your transportation funds.” It ended up that many of those cuts didn’t happen, thank goodness. But districts can’t fire staff in January. Districts with reserves had the choice to gamble that the money would be there; districts without reserves had to make those cuts or face insolvency or much much larger cuts for future years. Many districts got lucky and the cuts that looked certain didn’t happen. That money went into reserves.

Small districts also have a great deal of volatility in enrollment. A couple of families moving in or out can mean 10 students +/-, and that’s roughly $100k. For a district with a $3 million budget, that’s ~ 3%… ie, almost the entire 4% difference between the minimum legal reserve and the maximum legal reserve.

To give this as a household analogy, that means if you make $100k a year, you’d only be allowed to have $3,000 in liquid savings. That’s not “you can put away $3k a year.” It’s “you can’t accumulate more than $3,000.”

This is not to mention that $100k is not a lot of cash in the event of an emergency, like a boiler failure, major school bus repair, etc.

An ongoing steady reserve is NOT robbing from the current year’s students. If that reserve is not growing, then the money budgeted for the current year is exactly what is received. The reserve ALLOWS all that money to be budgeted for expenditures in the current year.

The problem with this law is that it encourages – even obligates – districts to hide money into designated reserves – and this makes it much much harder to understand a districts true needs and finances, for board members, for staff, and the community. It is much much better to have that 17% or 20% or whatever it is clearly designated as unallocated reserve, so that all the stakeholders can know it is there and how much it is, and rational conversations can be had about whether those reserves are prudent, are excessive, or should be spent on a one-time project like renovations or technology or supplies.

Paul 9 years ago9 years ago

This is directed more at the (usually thorough and unbiased) LAO than at you, el. A report that shows annual increases in reserves during the recession and mentions temporary federal funding, but that gives no specific data about whether, when and how reseves were spent, is not worth the paper it's printed on. Apart from keeping reserves to justify budget certifications or secure higher credit ratings, and dipping into reserves temporarily to meet cashflow needs, there's no evidence … Read More

This is directed more at the (usually thorough and unbiased) LAO than at you, el.

A report that shows annual

increases in reserves during the recession and mentions temporary federal funding, but that gives no specific data about whether, when and how reseves were spent, is not worth the paper it’s printed on.

Apart from keeping reserves to justify budget certifications or secure higher credit ratings, and dipping into reserves temporarily to meet cashflow needs, there’s no evidence in the report that reserve money was necessary or was used. On an aggregate, statewide basis, the money cannot have been spent (really spent, i.e., not simply borrowed until deferrals were paid) if reserves grew during the recession and have remained at recessionary levels ever since.

The whole point of building a reserve is to be able to spend the money during hard times. Not only was the money not spent, but more was added the recession, and it’s still sitting there afterward!

It’s also telling that the LAO report is silent on the question of maintenance of effort as a requirement for the temporary federal funds (ARRA).

ann 9 years ago9 years ago

"The CTA had complained that districts were hoarding a bonanza of post-recession funding that it argued should be spent on student programs and services.....spent on student programs and services" That's funny. In my district they told teacher's it should be spent on salaries and benefits..... Read More

“The CTA had complained that districts were hoarding a bonanza of post-recession funding that it argued should be spent on student programs and services…..spent on student programs and services” That’s funny. In my district they told teacher’s it should be spent on salaries and benefits…..

Replies

Tom 9 years ago9 years ago

Same happened at our District last year ann. All employees received generous salary increases and one-time payments, starting with the teachers, and passed on. Private sector employees have not gotten such treatment – just look at the stagnant wage increase data. Must be nice to be in a politically powerful union(s). This on top of Districts having to contribute more and more each year to support the underfunded teacher pension obligations. Thanks Gov.

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

Tom: You have defined your own problem as well as the solution. Wages have been stagnant. That is a problem not only for the wage earner, but for the entire economy as many legitimate economists have stated. The US economy, going full tilt, is based 70% on consumption. If the working population has stagnant wages, they cannot consume, the economy stalls or economic recovery is halting and constrained. The fact that unionized workers have, to some … Read More

Tom:

You have defined your own problem as well as the solution.

Wages have been stagnant. That is a problem not only for the wage earner, but for the entire economy as many legitimate economists have stated. The US economy, going full tilt, is based 70% on consumption. If the working population has stagnant wages, they cannot consume, the economy stalls or economic recovery is halting and constrained. The fact that unionized workers have, to some extent, been able to counter the trend is not cause to condemn the unionized workers, it should be to extoll those workers and their unions. At one time many more private sector worker were unionized. Not only were their increasing wages good for them and the economy as a whole, but that also pressured the non-unionized sectors to increase wages and benefits. It is only after a long period of ant-union conservative governments, beginning in the 1980s, that wages have not kept up with productivity. It is easy to find charts that show the flattening of private sector wages and the parallel decline in unionized private sector workers. It is to the economic benefit of workers, both private and public sector, and the economy as a whole to support the efforts of the public sector unions. It is the intent of conservatives to drive a wedge of jealousy between the public and private sector working class. That strategy works all too well and often.

It should only be common sense that after a period of 7 years of wage declines and stagnation that workers who have the capacity to do so catch up in compensation to earn what should be theirs. Don’t let union envy undermine the common sense aspects of what is going on.

The solution? Support unionized workers whatever their sect and explore getting a union in your own occupation.

navigio 9 years ago9 years ago

Totally agree with this.

The question is whether school board fiduciary responsibiility prohibits them from acting with these interests at heart.

Tom 9 years ago9 years ago

And therein lies the rub Nav – fiduciary responsibility, and more specifically, children first, adults second.

navigio 9 years ago9 years ago

well, I think its difficult to imply an 'order' to those responsibilities as they are generally not entirely mutually exclusive. note that a board responsibility is also to that of the district, and to provide for dedicated employees, without which, the interests of students are not served. instead, my point was that the reason for any board action probably can never be to try to address any historical compensation inequities in the general labor market. And … Read More

well, I think its difficult to imply an ‘order’ to those responsibilities as they are generally not entirely mutually exclusive. note that a board responsibility is also to that of the district, and to provide for dedicated employees, without which, the interests of students are not served.

instead, my point was that the reason for any board action probably can never be to try to address any historical compensation inequities in the general labor market. And as important as it might be for everyone to benefit from some aspects of what unions bring, I think its far fetched to imagine that a school board has any role in trying to increase unionization in the general economy.

As a union leader, or former one, gary has every right to believe increased unionization would be good for the country. I might even tend to agree with him on that. But I dont think he can expect school board members to be the levers through which that happens. In fact, asking them to do that I think would incite a breach of ficuciary responsibility (and perhaps even a conflict of interest).

Tom 9 years ago9 years ago

Gary, Agree that stagnant wages are a problem, but forcing higher wages through unionization and government force (think minimum wage increases) has the exact opposite affect on our economy, but I know we will never agree on this. It is indisputable that this country through freedom and capitalism has created the highest standard of living for the most people in the history of the world. There is no use in nibbling around … Read More

Gary, Agree that stagnant wages are a problem, but forcing higher wages through unionization and government force (think minimum wage increases) has the exact opposite affect on our economy, but I know we will never agree on this. It is indisputable that this country through freedom and capitalism has created the highest standard of living for the most people in the history of the world. There is no use in nibbling around the edges to try and fool some people to your socialist, big-government beliefs. Just wish you would be more objective and open-minded. The truth shall set you free!

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

Tom: What you ,is is that "good for the economy" and "good for unions" and good for the "nation at large" (aka, the majority of people) are all wrapped in one package. As union membership and bargaining power went up, so did middle-class growth and economic well being and so did the growth in the economy. They are all wrapped in the same package. This is not a matter of opinion. The economic data from the end … Read More

Tom:

What you ,is is that “good for the economy” and “good for unions” and good for the “nation at large” (aka, the majority of people) are all wrapped in one package. As union membership and bargaining power went up, so did middle-class growth and economic well being and so did the growth in the economy. They are all wrapped in the same package.

This is not a matter of opinion. The economic data from the end of WWII to today is well known and the interpretation is clear. As unions gained power the economic outcomes you talk about are clear. Just look at the data.

FloydThursby1941 9 years ago9 years ago

Gary we are not raising a lot of poor kids to reach the middle and upper middle classes. Let’s be real. California has incredibly powerful teacher’s unions that control everything and generations of kids are mired in poverty.

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

Ann:

So, what “student programs and services” were you thinking of that does not include the school personnel to provide the services and run the programs for the kids?

In this time of growing teacher shortage, and particularly for specialist teachers, districts that do not remain competitive in salaries will be at a terrible disadvantage for trying to provide any “student programs and services.”

Tom 9 years ago9 years ago

MORE teachers would be nice Gary instead of greater compensation! The union membership numbers would grow as well. Smaller class sizes, more remedial help. Kind of obvious benefits to this approach don’t you think?

el 9 years ago9 years ago

Most districts I've observed have in fact been adding more teachers. It's why there are articles about a teacher shortage all of a sudden, after years of districts enjoying 20 applicants for each position. There's an interesting game of musical chairs going around, as teachers shift from lower paying and less desirable districts/positions to more desirable ones. Districts paying below the median in particular are finding that they may need to increase compensation to keep … Read More

Most districts I’ve observed have in fact been adding more teachers. It’s why there are articles about a teacher shortage all of a sudden, after years of districts enjoying 20 applicants for each position. There’s an interesting game of musical chairs going around, as teachers shift from lower paying and less desirable districts/positions to more desirable ones. Districts paying below the median in particular are finding that they may need to increase compensation to keep their current staff and attract new applicants.

The count of FTE in a district is public record; you can look up the data yourself. You would want to adjust that number with the student count to see if class sizes went up or down.

Paul 9 years ago9 years ago

Show us the jobs! Class sizes are settling above past levels. The teacher shortage, where reported, stems not so much from restored positions as from the staggering 74% decline in teacher credential program enrollment over 10 years (reported elsewhere on this site). K-3 class size has gone from 20, in participating districts, to 24, unenforced for several years yet. Ninth-grade academic class size reduction was eliminated, not merely scaled back and left unenforced like K-3 CSR. English … Read More

Show us the jobs! Class sizes are settling above past levels. The teacher shortage, where reported, stems not so much from restored positions as from the staggering 74% decline in teacher credential program enrollment over 10 years (reported elsewhere on this site).

K-3 class size has gone from 20, in participating districts, to 24, unenforced for several years yet.

Ninth-grade academic class size reduction was eliminated, not merely scaled back and left unenforced like K-3 CSR. English 9 and/or high school Algebra I classes in former participating districts have jumped from 20 to 30+.

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

Tom:

As El notes, there is a current teacher shortage and concurrent rise in housing costs. Districts that don’t maintain competitive salaries don’t compete. There has been a years long shortage of specialists of various kinds because the costs to teachers of getting those specialist credentials took decades to recoup, Many specialist went into private practice as consultants costing districts twice the rate of teachers meaning most districts had to offer half the services. And teachers do have to live somewhere.