Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Republican legislators are continuing to push for passage of three California teacher reform bills, but it’s unclear what the status of the bills will be when the Legislature convenes in January.

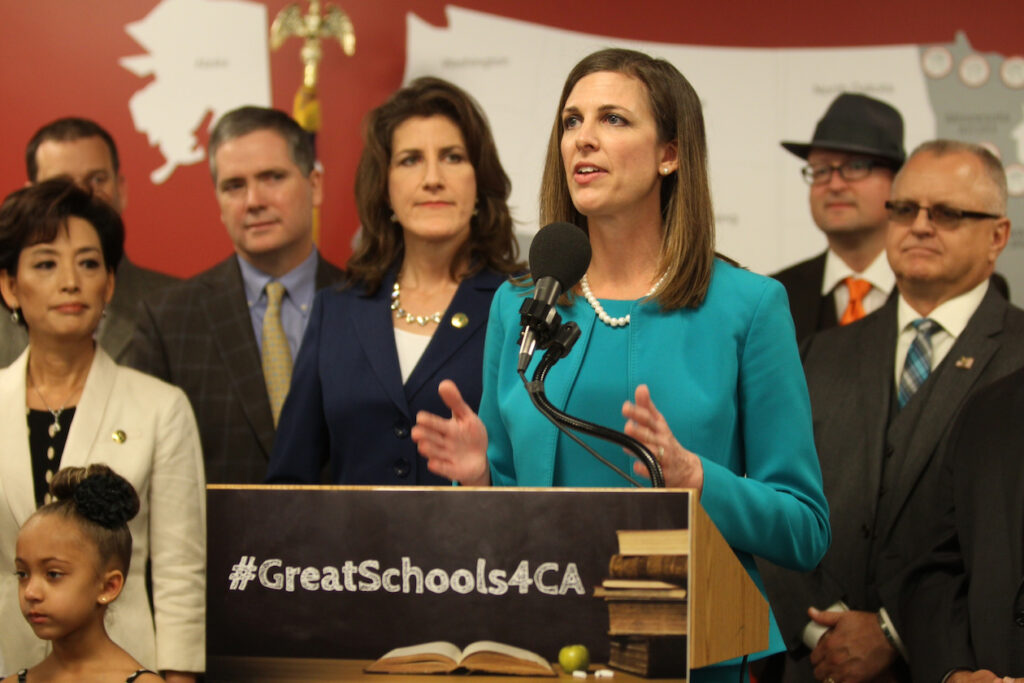

The Assembly Education Committee spent three hours discussing the bills last week, with no indication about whether the bills might come up for a vote next year. That lack of clarity frustrated the Assembly Republican leader and sponsor of one of the bills, Kristin Olsen, R-Modesto, who questioned why the majority of Democrats on the committee had voted to send the bills to “interim study,” a parliamentary tactic sometimes used when members don’t want to go on the record on controversial legislation. Interim study is an indefinite status that gives Education Committee Chairman Patrick O’Donnell, D-Long Beach, wide discretion to determine what, if anything, happens to a bill.

“In an effort to avoid casting ‘no’ votes on these worthy, important bills, the chairman and other members of this education committee invoked an obscure procedure that sent these bills to this interim study,” Olsen said. “And it truly saddens me that here we are, two weeks before Christmas, when people are out busy preparing for the holidays, that we’re holding a hearing when nobody is paying attention.”

The hearing was webcast but sparsely attended by the public; two of four Democrats on the committee were absent.

Assembly Republicans proposed the three bills as a package in response to the 2014 ruling in Vergara v. California, in which a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge overturned five California teacher protection statutes. Judge Rolf Treu ruled that the state’s two-year probationary period for new teachers, a layoff system based on teacher seniority and dismissal statutes that can make it difficult to fire the worst-performing teachers, violated students’ constitutional right to an equal education.

Democrats in the Legislature are letting the lawsuit, now before the State Court of Appeal, run its course. The Republican sponsors called on legislators to fix laws that Treu said are harming children. They expressed a willingness last week to work with Democrats on amendments to their bills.

Assembly Bill 1248, authored by Assemblyman Rocky Chavez, R-Oceanside, would extend the probationary period to three years. A teacher would have to receive three consecutive positive reviews before receiving “permanent status” or tenure, which grants additional legal protections to new teachers.

AB 1044, by Assemblywoman Catharine Baker, R-Dublin, would repeal the “last-in-first-out” statute that requires all teacher layoffs, with exceptions for teachers with specialized training or those who fill high-needs jobs, to be based on seniority. Districts would negotiate new criteria with their teachers unions. Seniority could be a factor, but a “significant” component must be based on a teacher’s evaluation rating.

Olsen’s bill, AB 1078, would update the 40-year-old law on teacher evaluations, the Stull Act. Democratic and Republican legislators generally agree it needs changes to reflect new challenges, such as the use of technology, new approaches to discipline and the substantial growth in the number of English learners, although after several years and multiple versions of bills they have yet to agree on how.

The Stull Act currently is a pass-fail system, with teachers labeled either ineffective or effective, which encourages principals to focus on how to fire a small fraction of those identified as the worst and not on evaluations that focus on how the majority of teachers can improve their craft. AB 1078 would create four categories (highly effective, effective, minimally effective and ineffective), require annual evaluations, and encourage what the current law requires but many districts ignore: the use of test scores and other measurements of student academic growth.

“Our immediate dilemma is not who to lay off but how to attract teachers for underrepresented students. There needs to be an agenda to match that sort of issue,” said researcher Julia Koppich.

“These laws are responsible for pushing wonderful, effective teachers out of the classroom just because they have less seniority, and this makes no sense,” Evelyn Macias, mother of one of the nine Vergara student plaintiffs, said in her one-minute public testimony. The California Teachers Association and the California Federation of Teachers opposed all three bills last year, and reaffirmed that position in brief public comments on Tuesday. Breaking with the California Teachers Association, teachers in San Jose agreed in negotiations for the option of a third year of probation for teachers who need an extra year to prove their capabilities; a bill permitting an exception to the law for San Jose remains in flux.

The three bills got mixed reviews from a panel of three experts that included Dan Goldhaber, a vice president at American Institutes of Research and a witness for the plaintiffs in the Vergara case, and Ken Futernick, retired director of the Center on School Turnaround at WestEd and a witness for the defense in the case. Futernick and the third panelist, researcher and consultant Julia Koppich, while not dismissing criticisms of a short probationary period and seniority-based layoffs, suggested that the focus now should be not on layoffs but on figuring out how to hire and retain teachers amid a teacher shortage.

“Our immediate dilemma is not who to lay off but how to attract teachers for underrepresented students. There needs to be an agenda to match that sort of issue,” Koppich said.

More students will be affected by the shortage of teachers than in not dealing with issues that the bills address, Futernick said. “We cannot recruit if no one wants to become a teacher.”

Goldhaber, however, said that research from several studies on teacher layoffs was “unanimous” and clear: Students, particularly minority students in schools where high turnover leads to a churn of less experienced teachers, are adversely affected when layoffs are done in order of seniority. “The research is consistent that if student achievement is the primary concern, then do not rely primarily on seniority” to lay off teachers, he said.

Source: California Channel webcast

Assemblywoman Shirley Weber, D-San Diego, said that an evaluation system with two categories, designating teachers as effective or not effective, will not provide ongoing assistance to teachers. Her bill, AB 1495, which the Education Committee defeated last spring, would have created a third category for teachers needing improvement.

The panel members acknowledged that a more effective system of evaluating teachers should be a prerequisite to a longer probation for teachers or a layoff system using teacher effectiveness as a standard.

“Just adding a year without improving the evaluation system is unlikely to have much, if any, effect,” Koppich said. “Until we have an effective system that distinguishes between high-quality teaching and less high-quality, it’s hard to design an objective system that is not based on layoffs.”

Getting there has been challenging. Teachers unions and groups representing schools boards and administrators remain deadlocked over who gets to decide what goes into an evaluation, such as classroom observations, test scores and other measures of student achievement, and parent surveys. O’Donnell and Sen. Carol Liu, who chairs the Senate Education Committee, have proposed similar rewrites of the Stull Act that would require school boards to negotiate terms of evaluations with teachers, but those bills, too, are stalled for now, although they can be brought back in 2016.

“I’m not sure where we start since there has been so much resistance,” said Assemblywoman Shirley Weber, D-San Diego. Last spring, Weber’s bill, an attempt to bridge the divide between labor and management groups, was defeated by fellow Democrats.

“It’s been unfortunate that it appears the only way to address teacher issues is through litigation,” she said. “We need to figure out how to create a stronger teacher force and be supportive of the teachers we have.”

The overreliance on undersupported part-time faculty in the nation’s community colleges dates back to the 1970s during the era of neoliberal reform — the defunding of public education and the beginning of the corporatization of higher education in the United States. Decades of research show that the systemic overreliance on part-time faculty correlates closely with declining rates of student success. Furthermore, when faculty are… read more

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Comments (8)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Jeff Krause 8 years ago8 years ago

Even though I am a supporter of teachers’ unions, I am strongly in support of adding another year to the probationary period. The reality is that it is impossible for administrators to make an informed decision about a young teacher by March of year 2. A third year would allow beginning teachers to have a chance to improve.

CarolineSF 8 years ago8 years ago

EdSource has reported extensively on the critical shortage of teachers in California and elsewhere. How does the continuing notion that we need to lengthen probation periods, remove teachers' job security and due process, implement more draconian evaluations and generally crack down and smack them around jibe with the need to attract more people to teaching? Also, in no other profession is it viewed as normal behavior to not only create and implement education policy … Read More

EdSource has reported extensively on the critical shortage of teachers in California and elsewhere. How does the continuing notion that we need to lengthen probation periods, remove teachers’ job security and due process, implement more draconian evaluations and generally crack down and smack them around jibe with the need to attract more people to teaching? Also, in no other profession is it viewed as normal behavior to not only create and implement education policy and so-called “reforms” without consultation with or involvement of teachers, but to treat teachers as malevolent impediments whose goals and interests are harmful to the children they teach. And to implement policy after policy over the objections of the teaching profession? Is Bill Gates treating medical professionals that way in his projects to eradicate malaria, for example?

Replies

Roger G 8 years ago8 years ago

Caroline, it is interesting that you mention Bill Gates in your comment. It is evident that his involvement in education is not to enhance a public school teachers security or for that matter, to insure public schools in our future. Charter schools and the increased use of technologically enhanced programs seems to be his goal. Naturally that would enhance the profit motive in the new programs needed. That sounds like a sound big business goal in my judgment.

Julia 8 years ago8 years ago

How are you going to be able to attract new, motivated teachers into the teaching profession if they know that when an economic downturn comes - and it will come, one always comes - they will be the first to be sacked regardless of their merit (thanks to LIFO)? So, while it sounds nice and positive to talk about recruiting, retaining, and supporting teachers - that conversation cannot be done in a vacuum that … Read More

How are you going to be able to attract new, motivated teachers into the teaching profession if they know that when an economic downturn comes – and it will come, one always comes – they will be the first to be sacked regardless of their merit (thanks to LIFO)? So, while it sounds nice and positive to talk about recruiting, retaining, and supporting teachers – that conversation cannot be done in a vacuum that excludes layoff policies. I also argue that it’s better to address employment policies now, while schools have money. Change seems much less likely if everyone has their hackles up during an economic downturn.

Replies

CarolineSF 8 years ago8 years ago

Yet job security is also important to professionals, and has traditionally helped attract teachers to a difficult and underpaid career.

David Cohen 8 years ago8 years ago

LIFO could probably use some adjustment. I don't think anyone can say that bouncing teachers all around a large district and into grades or subjects they are ill-suited for is a good idea. However, seniority overall remains an appropriate consideration in the event that layoffs become necessary. Those who oppose seniority always seem to assume that the alternative can be done fairly and accurately, and without other consequences to the workplace. I'm skeptical on that … Read More

LIFO could probably use some adjustment. I don’t think anyone can say that bouncing teachers all around a large district and into grades or subjects they are ill-suited for is a good idea. However, seniority overall remains an appropriate consideration in the event that layoffs become necessary. Those who oppose seniority always seem to assume that the alternative can be done fairly and accurately, and without other consequences to the workplace. I’m skeptical on that front. If demographic and economic trends make layoffs seem possible, what exactly is the incentive for veteran teachers with long-standing connections to the community, and families to support, to provide their best support for their younger, cheaper replacements?

Roger G 8 years ago8 years ago

As we have talked about previously, it is quite evident that legislators are not really qualified to evaluate educators in a fair and representative manner. Putting that aside, it is necessary for all educators to stand together in a positive stand against having arbitrary methods legislated to simply use test scores and administrative decisions in dismissing an educator when they are coming up for permanent status. I do feel that extending the probationary period … Read More

As we have talked about previously, it is quite evident that legislators are not really qualified to evaluate educators in a fair and representative manner. Putting that aside, it is necessary for all educators to stand together in a positive stand against having arbitrary methods legislated to simply use test scores and administrative decisions in dismissing an educator when they are coming up for permanent status. I do feel that extending the probationary period from two to three years would be a positive negotiating point for unions to use in dealing with a school district.

Bill Younglove 8 years ago8 years ago

Evaluation of teacher performance is not rocket science. Solid research backs the idea of nurturing teachers over time. Growth toward worthwhile pedagogical goals should be at a premium. Teachers’ professional judgments are arrived at after years of meaningful classroom experiences. Teach for Awhile, and other such gimmicks, simply will not do it. Multiple measures of instructional practices can best assure quality.