Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

What happened at a rural high school was, according to a new guide to school discipline, the starting point for change. Faced with chronically tardy students and a steady stream of office referrals, including a disproportionate number of American Indian students, school administrators asked: Why? Why the lateness? Why the office referrals?

With schools across California and the nation working to reform discipline practices — either voluntarily or under legal pressure — the guide, “Addressing the Root Causes of Disparities in School Discipline: An Educator’s Action Planning Guide,” is intended as a tool to help schools “look for the whole story” behind who is disciplined and why. Produced by the American Institutes for Research for the U.S. Department of Education, the guide offers schools a data-informed road map for improving school climate and reducing discipline disparities.

“People are feeling the pressure to do something immediately,” said David Osher, a vice president at the American Institutes for Research and the lead author of guide. “The purpose of the guide is to help people do something immediately, but do something with strategic analysis.”

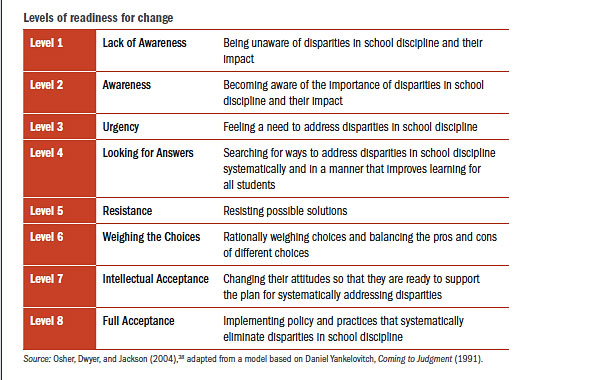

In the process of changing the uneven application of school discipline, school staff move from lack of awareness to full acceptance of the fact that some groups of students are disciplined more harshly than others, according to a U.S. Department of Education action guide for educators.

Driving the need for discipline reform, the guide noted, are discriminatory discipline practices in schools nationwide, according to an issue brief from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. Students of color, students with disabilities and students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender are disproportionately subject to school suspensions, the guide said. The impact on students, families, schools and the community “is serious and the cost is high,” the guide said.

Rather than a prescription for how schools should change or who is at fault for the way things are, the guide is intended to provide a structure for making change, Osher said.

“If people are going to do this well, we have to go beyond blame or guilt,” he said. “It’s rather a problem-solving approach.”

Step by step, the guide outlines how schools can conduct a “root cause analysis” to understand what underlies school discipline disparities and how to take corrective action.

The process is hands-on. A “Discipline Data Checklist” and a “Data Mining Tip Sheet” can help schools organize student data, collected from school databases or government agencies, about attendance, the time and place of discipline infractions, race, disability, ethnicity and more. The “Disciplinary Disparities Risk Assessment Tool” is a series of formatted Excel spreadsheets with instructions on how to enter and interpret discipline data.

Also included are examples of what’s happened at other schools, ideas about building a school climate team and tips for how to guide “courageous conversations” about sensitive topics, including race, ethnicity, culture and classroom-management styles.

In the case of the rural high school detailed in the guide, the root cause analysis included sorting attendance data by gender and race. That revealed that more girls than boys were arriving late to school and that among the students referred to the office for tardiness, “a significant percentage” were American Indian, according to the guide, which did not cite specific numbers.

“Talking to kids ought to be a basic step,” said David Osher of the American Institutes for Research. “Young people have a lot to say about what doesn’t work.”

The assistant principal then set out to talk to students and teachers at the school, which is located in Wisconsin but was not identified by name. Osher said that conversations with students are invaluable, yet often overlooked. “Talking to kids ought to be a basic step,” he said. “Young people have a lot to say about what doesn’t work.”

Some students said they were late because they lived far away. Others had to bring a sibling to school first. Still others said the only time they had to talk with friends was before school.

In the schema of the root cause analysis, these were the causes.

As for the office referrals, some teachers said they regularly argued with and disciplined a group of students who were both late and unprepared for class.

The analysis also went a level deeper. At the high school, a team of teachers, administrators, staff members, students and community members — carefully selected to be both representative of the community and willing to work together — talked about the data and the reported causes. The conversation was revealing.

The team learned that school buses didn’t always run on time and that if the bus arrived at a stop early, the driver wouldn’t wait to pick up the students. They learned that bringing a sibling to another school was a real obstacle to students arriving by the first class bell at 7:45 a.m. And they learned that for some students in the widely scattered rural community, seeing their friends face to face in the morning meant more to them than getting to class punctually.

At the same time, the team learned that many of the teachers were new and unsure how to interact with American Indian students. Teachers said they didn’t realize that some students needed help with the curriculum, or that students’ bold behavior masked academic frustration. Teachers also hadn’t known that some students felt that teachers didn’t care about them.

Straightforward action corrected the school bus issue. The bus schedule was moved up five minutes and drivers received a brief training to discuss issues and reinforce the practice of not leaving pick-up stops before the scheduled departure time.

To address the need for academic support and to provide students with a chance to connect in the morning, the assistant principal received permission from the district to shift the school start time to 8:15 a.m. — 30 minutes later — and to set aside the time from 7:45 to 8:15 a.m. for students to do homework and seek help from teachers.

On the social front, the school contacted a local American Indian tribal community center and invited members, including parents of students, to come talk with teachers. In addition, community center members were invited to volunteer as campus greeters at arrival time in the morning.

Within a few weeks of the changes, the number of students marked tardy or sent to the office for misconduct “decreased significantly,” the guide said.

The example is not meant to suggest that change in student-teacher relationships and discipline policies comes easily, the guide notes. Rather, it shows that once root causes are identified, relatively simple adjustments can build momentum for long-term shifts in practices, Osher said.

Osher said that the guide, which was released at a national White House conference for educators called “Rethink Discipline” on July 22, is not a stand-alone tool. It includes links to resources on positive discipline and so-called restorative practices that allow students to make amends for misbehavior. Along with the guide, the U.S. Department of Education launched a Rethink Discipline initiative and released an interactive map showing school suspension rates across the country.

But Osher said that to make effective change, schools need to start by understanding what’s really going on, and the guide is one way to conduct a thorough review of school policies and data, as well as the experiences of teachers, students and community members.

“This is about systemic change,” he said. “This is not about just fixing one teacher or one kid.”

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (9)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Don 8 years ago8 years ago

Read today's revealing article in the LA Times about how the new suspension and discipline rules are wreaking havoc on schools, students and learning. I can't help myself but say - I told you so! http://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-school-discipline-20151108-story.html Here's an excerpt: "My teachers are at their breaking point," Art Lopez, the school's union representative, wrote to union official Colleen Schwab in a letter obtained by The Times (LA). "Everyone working here is highly aware of how the lack of consequences … Read More

Read today’s revealing article in the LA Times about how the new suspension and discipline rules are wreaking havoc on schools, students and learning. I can’t help myself but say – I told you so!

http://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-school-discipline-20151108-story.html

Here’s an excerpt:

“My teachers are at their breaking point,” Art Lopez, the school’s union representative, wrote to union official Colleen Schwab in a letter obtained by The Times (LA). “Everyone working here is highly aware of how the lack of consequences has affected the site. Teachers with a high number of students with discipline issues are walking a fine line between extreme stress and a emotional meltdown.”

Lopez wrote that many teachers felt that administrators were pushing the burden of discipline onto instructors because they can no longer suspend unruly students and lack the staff to handle them outside the classroom. Associated Administrators of Los Angeles, which represents principals and others, declined to comment.

Michael Lam, an eighth-grade math teacher, said he has seen an increase in student belligerence under new discipline policies.

“Where is the justice for the students who want to learn?” he said, speaking at a recent forum held as part of the process to select the next superintendent of schools. “I’m afraid our standards are getting lower and lower.”

Don 9 years ago9 years ago

OK, so they do a root cause analysis. They discover students who live far away have difficulty getting to school on time due to bussing issues and that some students prefer to interact with friends before school because they say that is more important to them. Teachers also discover that some students are having trouble with the curriculum and these students feel their teachers don't care about them. A remedy for the … Read More

OK, so they do a root cause analysis. They discover students who live far away have difficulty getting to school on time due to bussing issues and that some students prefer to interact with friends before school because they say that is more important to them. Teachers also discover that some students are having trouble with the curriculum and these students feel their teachers don’t care about them.

A remedy for the tardiness and preparedness issue entails moving the start time forward half an hour. Instead of school starting at 7:45 it begins at 8:15 which allows for a 30 minute homework/tutoring period. Students who live far away have more time to travel to school and be on time and it provides students the opportunity to see their friends face-to-face before school because they think that is more important. But wait a minute. If students need 30 minutes more to get to school how are they to access the opportunity afforded by this 30 minute period? And why is it that teachers are unaware of students having problems in school when they arrive habitually late and unprepared? Were they getting good grades? I don’t think so. Students think the teachers don’t care about them and they appear to be correct.

It is also revealing to look at the use of the word “bold” as in, ” Teachers said they didn’t realize that some students needed help with the curriculum, or that students’ bold behavior masked academic frustration.”

The use of the word “bold” is a strange one. In fact the whole sentence is odd. Referring to behavioral outbursts as “bold” is one of the most extreme examples of political correct speech I’ve encountered. Did teachers put out a joint statement or is this a summarization by Ms. Adams? And what are these teachers thinking? Of course students who act out in class are having trouble with the curriculum as well as making it difficult for the other students to access it,too. Did they think the “bold” behavior was just good fun? But no need to worry. There’s a solution to the rescue thanks to Root Cause Analysis, the Discipline Data Checklist, the Disciplinary Disparities Risk Assessment Tool and the Data Mining Tip Sheet. Hey, I have a tip for the school. Don’t implement a before school program before the students can be reasonably expected to arrive at school.

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

From the article: “If people are going to do this well, we have to go beyond blame or guilt,” he said. “It’s rather a problem-solving approach.” No "blame" and no "guilt?" Obviously, someone has no idea about the "fundamentals" of contemporary "school reform." And "problem-solving" in order to solve actual school problems. Who came up with all of this? Read More

From the article:

“If people are going to do this well, we have to go beyond blame or guilt,” he said. “It’s rather a problem-solving approach.”

No “blame” and no “guilt?” Obviously, someone has no idea about the “fundamentals” of contemporary “school reform.” And “problem-solving” in order to solve actual school problems. Who came up with all of this?

Don 9 years ago9 years ago

Ms. Adams, could you define what you believe is meant by the term "discipline disparities" as it apparently relates in this context to various subgroups of students, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, language, etc? Does it mean discipline/consequences rates should be proportional to a given population or is it something else? I can't understand this article precisely unless I'm aware of the definitions of some of the terms as used, discipline disparities in particular, but … Read More

Ms. Adams, could you define what you believe is meant by the term “discipline disparities” as it apparently relates in this context to various subgroups of students, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, language, etc? Does it mean discipline/consequences rates should be proportional to a given population or is it something else? I can’t understand this article precisely unless I’m aware of the definitions of some of the terms as used, discipline disparities in particular, but also “discriminatory discipline practices.”

I don’t disagree with what could be construed as a factual statement that “Students of color, students with disabilities and students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender are disproportionately subject to school suspensions…”. The popular assumption from reading that statement would be that something is necessarily wrong because the use of the root word “proportionate” isn’t clear enough and could be misleading. For example, if you say the amount of fat in your milk is disproportionate that sounds to me like the milk is bad, but I’d need to know the context – in comparison to whole milk, low fat milk or fat-free milk. What the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is trying to say, I believe, is that discipline rates, e.g., suspensions, expulsions, etc. for subgroups of students are not proportional to their overall population size because the data documents a disproportional relationship. They are speaking about strict data-driven proportionality, not some general misalignment. Since a person (or group) should say what she means and mean what she says, the Office for Civil Rights should say that these subgroup rates ought to be in proper proportion to their respective populations rather than simply imply that there is a problem because they are not proportionate, a word that is sometimes defined as having an agent outside of the strict math involved in proportionality responsible for the difference. That means it could be placing blame for a lack of proportion and in this case the blame is considered “discriminatory practices”. The Civil Rights Office should just come out and say it – discipline practices are racist because that’s what they apparently mean based upon the context of the entire issue as presented in the media. How can any reasonable-minded person or persons claim that some individuals student groups are disciplined fairly, but if their numbers go above strict proportionality, the same practices are racist? That is in no way to be confused with practices by individuals that might be racially motivated.

Rik Blumenthal 9 years ago9 years ago

I think the bus situation described is worthy of note and a reasonable argument for change, but shortening the school day by 15 minutes (I saw no mention of shifting the end of school) may cover up the issue but only by injuring the on-time and the formerly late students.

Paul Muench 9 years ago9 years ago

Just a nit, but I would have thought the awareness step would include developing the understanding that disparities actually existed in your school. Someone may understand that the topic is important, but think it is only a problem in other schools.

Replies

navigio 9 years ago9 years ago

My impression from the wording that this is a goal. Note "school staff move from lack of awareness to full acceptance of the fact that some groups of students are disciplined more harshly than others," IMHO, the part that may be left out is the role of district (as opposed to school) admins in this issue. I think it's much easier when people are physically separated to make problematic generalizations. It's true their behavior ray not … Read More

My impression from the wording that this is a goal. Note “school staff move from lack of awareness to full acceptance of the fact that some groups of students are disciplined more harshly than others,”

IMHO, the part that may be left out is the role of district (as opposed to school) admins in this issue. I think it’s much easier when people are physically separated to make problematic generalizations. It’s true their behavior ray not impact as directly or as often, but when your goal is systemic responsibility then everyone needs to be involved in the introspection.

Jane Meredith Adams 9 years ago9 years ago

Hi Paul.

You’re right. That is the first step — using the data to figure out that disparities actually exist in your school.

Jane

Paul Muench 9 years ago9 years ago

Ah…I didn’t interpret the wording of the first step as being that specific.