Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

While the state’s standardized testing program is being revamped during the transition to the new Common Core State Standards, the fate of the high school exit exam – the one test students must pass – remains murky.

In overhauling the state assessment system last year, officials postponed a decision about the exit exam, which students need to pass in order to receive a high school diploma. Most other tests are on temporary hiatus while students take a practice test aligned to Common Core. The voluntary standards, adopted by California and 42 other states, set common requirements for what students should know in math and English.

But the exit exam – aligned to the old state standards – remains in place as a requirement for graduating seniors. The most recent scores, for the class of 2014, are expected to be released Friday.

Officials must now return to discussions about the future of the California High School Exit Exam, whether or how it should be revamped to meet the Common Core standards and whether it should be required as a separate assessment at all.

Any change to the test would require action in the Legislature, and state officials could seek clarity on the exam when the next legislative cycle begins in December, said Diane Hernandez, director of the assessment development and administration division of the California Department of Education.

“We want to have conversations about whether to continue with the graduation assessment first, and second, what that could be,” Hernandez said.

The 2013 law that suspended most testing requirements, Assembly Bill 484, was mum on the exit exam, but did set a 2016 deadline for the State Board of Education to present a comprehensive testing plan to the Legislature.

A January 2013 report from State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson recommends considering “alternatives” to the exit exam. Among them:

The results of the Smarter Balanced tests could be one predictor of the future of the exit exam.

California Department of Education

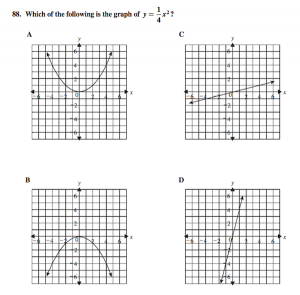

A sample algebra question from the California High School Exit Exam. Click to enlarge. Answer: A

Students in grades 3 through 8 and 11 tried out the test in practice sessions this school year. Students will begin taking the real test in spring 2015 and the first meaningful results could be available by summer 2015, said State Board President Michael Kirst.

The tests go beyond the multiple-choice assessments of the past and are designed to test critical thinking and reasoning skills. And the tests are computer adaptive, meaning the questions get easier or harder, depending on how many questions a student answers correctly. Officials anticipate the new tests will provide a better understanding of student strengths and weaknesses and more meaningful results on academic progress.

“I think once we see the Smarter Balanced results we will know more” about what to do with the exit exam, Kirst said. “It’s possible that once we see what’s going on with that, we could rethink the high school exit exam. We want to see what that adaptive ability adds to our understanding of the high school exit exam.”

California isn’t alone in grappling with the issue, Hernandez said. The more rigorous academics required under Common Core are prompting a number of states to revisit their exit exam requirements.

A goal of Common Core is that students graduate with the skills they need to succeed in college and careers, raising questions about the role of an exit exam under the new standards and sparking discussions about the meaning of a high school diploma.

The exit exam was created in 1999 under a state law authored by Sen. Jack O’Connell, who later became state superintendent of public instruction. The exam’s purpose was to ensure that students met basic proficiency in math and English before they obtained high school diplomas, but not to measure the higher bar of whether students were academically ready for college-level work.

Richard Duran, a UC Santa Barbara professor who sits on a California Department of Education technical advisory group on the exit exam, said it would be a mistake to eliminate the exit exam and rely instead on the Smarter Balanced tests to confer diplomas.

“The issue is what do we mean by being qualified to receive a high school diploma,” Duran said. “If that diploma is dependent on a test, and if that test were to be the (Smarter Balanced) test that could only be passed by being college ready, it would be a disaster. It would mean that a larger percentage of students would not receive the high school diploma.”

The exit exam, he said, was not intended to be a measure of college readiness.

“I don’t think that’s fair for students to have to be kind of caught in the middle there while our policy makers figure out how to help them,” said Jeannette LaFors, director of equity initiatives at The Education Trust-West.

The exit exam includes two portions – a math section that tests sixth- and seventh-grade material and Algebra I, and an English language arts portion that tests up to 10th grade material. Students have numerous chances to take the test, beginning in 10th grade.

Passage rates on the exam have grown incrementally each year, from a 90.4 percent passage rate in 2006 to the highest yet – 95.5 percent – for the class of 2013.

Hernandez and others give the test credit for improving academics and allowing for targeted instruction for struggling students, boosting graduation rates, reducing dropout rates and increasing the number of students who are taking algebra and advanced math classes.

Yet low-income students and English learners pass the test at lower rates than other students. Eighty-two percent of English learners and 93.5 percent of low-income students passed the exit exam in 2013, state data show, and racial gaps remain. African-American students posted a 92 percent passage rate in 2013, while the passage rate for Latino students was 94 percent. That’s compared with a 99 percent passage rates for white students and a 98 percent passage rate for Asian students.

Students with disabilities also struggle with the test, and a state law allows disabled students to receive a waiver from having to pass the exam to receive a diploma. Such students are encouraged to take the test, however.

Until the test’s fate is settled, “we continue to administer the (exit exam) as we have always done,” said the education department’s Hernandez. Current students have six more chances to take the test – still pegged to the state’s previous academic standards – before the school year ends.

It’s unclear how the mismatch between what’s being taught and what’s being tested might affect students.

On the one hand, the more rigorous standards associated with the Common Core could mean that students perform “as well or better” on the exit exam, said Jeannette LaFors, director of equity initiatives at The Education Trust-West, a nonprofit policy and educational equity advocacy group.

But “it could also be a real adaptation challenge for students,” she said, especially for students who require additional preparation and remediation classes to help them pass the exit exam.

“I don’t think that’s fair for students to have to be kind of caught in the middle there while our policy-makers figure out how to help them,” LaFors said.

“Whoever is in charge of that assessment plan,” she added, “I hope they are up at night.”

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (19)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

griselda 9 years ago9 years ago

i honestly don’t think this should be an requirement to graduate. I still haven’t got my diploma since 2013.I mean high school has so many requirements all ready just making more hard by having to pass the dam test. I only need he English and didn’t pass by two point witch is ridiculous if you ask me.I just want to be successful in life go to college and be a RN and then do LVN.

Replies

Parents News Opinion 9 years ago9 years ago

Dear Student Griselda, . . Good ideas stated by you. Thank you. I say, the educational system failed you and the educational system is maybe afraid of hundred of thousands of high school students who got lots of hugs and well wishes by middle school teachers and high school teachers who did not do a good job in teaching you. If you google "TEACHERS CHEAT ON HIGH STAKES TESTING," you may even come to the … Read More

Dear Student Griselda,

.

.

Good ideas stated by you. Thank you. I say, the educational system failed you and the educational system is maybe afraid of hundred of thousands of high school students who got lots of hugs and well wishes by middle school teachers and high school teachers who did not do a good job in teaching you. If you google “TEACHERS CHEAT ON HIGH STAKES TESTING,” you may even come to the conclusion that in tears past, when you attended middle and high school many teachers all over we’re caught erasing the answers on the annual state testing, so, the California Leaders went to a computer test, so the results will be cheat proof, which will prove out that students need not take the CAASEE high school exit exam, cause, students are robbed of good education and given some inflation for report card scoring, huh, what you say to dis.

So, use Internet and push for your h.s. diploma cause if all the other h.s. students get a diploma without you getting one, then that no fair.

Parents Opinion News

Don 10 years ago10 years ago

Isn't it the case that the ultimate substantiation of college readiness can only be made once students have completed their first year of post-secondary education? Which kinds of assessments, (if other than GPA), are made at that time? And if GPA is used as a general litmus test of success, wouldn't grades, being a lower quality and highly subjective assessment metric, provide the "lowest common denominator" in the college readiness equation, calling into question … Read More

Isn’t it the case that the ultimate substantiation of college readiness can only be made once students have completed their first year of post-secondary education? Which kinds of assessments, (if other than GPA), are made at that time? And if GPA is used as a general litmus test of success, wouldn’t grades, being a lower quality and highly subjective assessment metric, provide the “lowest common denominator” in the college readiness equation, calling into question the viability of SB as a useful measure of readiness (its API-type compliance function withstanding)?

Paul Muench 10 years ago10 years ago

Will the Smarter Balanced test results provide two different sets of cut scores? One for college ready and one for career ready. I don’t see any indication of that on the Smarter Balanced website.

Replies

Doug McRae 10 years ago10 years ago

That's an interesting question, Paul. I've tried to follow SB's plans as closely as I can, and I haven't heard anything about separate cut scores for college ready and career ready. Rather, my understanding is that SB will have a single set of cut scores designed for use for federal accountability (i.e., AYP or whatever it becomes) with eventually some comparability between SBAC and PARCC cut scores to allow for comparability of scores among all … Read More

That’s an interesting question, Paul. I’ve tried to follow SB’s plans as closely as I can, and I haven’t heard anything about separate cut scores for college ready and career ready. Rather, my understanding is that SB will have a single set of cut scores designed for use for federal accountability (i.e., AYP or whatever it becomes) with eventually some comparability between SBAC and PARCC cut scores to allow for comparability of scores among all consortium testing states. While presumably the consortium cut scores would be required by the feds for their purposes, individual states could have separate cut scores for their own purposes [say, general accountability ala API for California or specific programs with something like use for high school exit purposes frequently mentioned as a state determined cut score use that the consortium won’t monkey with]. But, this understanding is not based on any definitive information from SBAC or CDE on how the SB cut scores will be used . . . . . recall that final or valid SB cut scores won’t be available until fall 2015 (probably Sept 2015) so there is some time for additional water to flow beneath the SB bridge.

Your question about separate cut scores for college ready and career ready kinda assumes a single cut score for each purpose would be appropriate. Not necessarily the case. We’ve never had a single cut score on college entry exams, for example . . . . each college sets their own “cut” score for admissions purposes with scores needed for highly competitive schools such as Stanford a whole bunch higher than cut scores for less competitive colleges to no cut scores at all for (say) CA Comm Colleges. And the picture is even more complex on the career readiness side . . . . STEM careers have much higher cut scores on science and math than (say) law or humanities careers, and for the trades there are substantial differentials in potential cut scores on E/LA and Math needs for different trades areas. The entire area of establishing test cut scores for different purposes and different groups of students is very fraught with complexity, to say the least.

Paul Muench 10 years ago10 years ago

Does that mean that the single pass/fail result of the high school exit exam is not really useful to anyone?

Doug McRae 10 years ago10 years ago

Paul -- I'm not sure what you are asking. A single CAHSEE score will always have meaning for the student, and CAHSEE is primarily an individual student test in terms of high stakes. If what you are referring to reflects how CAHSEE scores contribute to a group accountability system result, well, we have used CAHSEE for federal group accountability at the high school level for the past ten years but frankly that wasn't one of … Read More

Paul — I’m not sure what you are asking. A single CAHSEE score will always have meaning for the student, and CAHSEE is primarily an individual student test in terms of high stakes. If what you are referring to reflects how CAHSEE scores contribute to a group accountability system result, well, we have used CAHSEE for federal group accountability at the high school level for the past ten years but frankly that wasn’t one of the main purposes for having CAHSEE in the first place. It is a bit of an unfortunate story how California ended up with a less than desirable tool for federal group accountability, and didn’t find a way to jettison use of CAHSEE for federal accountability over the past ten years. But I think your question is aimed at individual student use, and a single CAHSEE result will always have some meaning for the student who takes the test.

Paul Muench 10 years ago10 years ago

Let me clarify. One idea of a high school diploma is that it tells employers something about potential employees. So I was motivated to question what value the exit exam adds to a diploma by your comment about the variety of meanings for career ready. So sure the exit exam result is useful to a student, because that is the only measure that exists. But due to its single pass/fail nature … Read More

Let me clarify. One idea of a high school diploma is that it tells employers something about potential employees. So I was motivated to question what value the exit exam adds to a diploma by your comment about the variety of meanings for career ready. So sure the exit exam result is useful to a student, because that is the only measure that exists. But due to its single pass/fail nature how much value does the current exit exam really add?

Doug McRae 10 years ago10 years ago

Paul [ran out of reply arrows, not sure where this is going to be placed] -- OK, to the employer the CAHSEE pass score indicates the applicant has the minimum achievement in E/LA and Math required for a HS diploma in California. None of the other scores from statewide testing indicates that . . . . tho good scores on CSTs or new SB tests infer the same, but for a student with poor scores … Read More

Paul [ran out of reply arrows, not sure where this is going to be placed] — OK, to the employer the CAHSEE pass score indicates the applicant has the minimum achievement in E/LA and Math required for a HS diploma in California. None of the other scores from statewide testing indicates that . . . . tho good scores on CSTs or new SB tests infer the same, but for a student with poor scores on CSTs or new SBs the employer does not know how the applicant’s E/LA and Math scores stack up against the standard needed to be granted a high school diploma. From a test developer perspective, however, one way to make a statewide testing system more efficient is to conduct comparability studies between the CAHSEE and other tests like CSTs and/or SBs so that one does know from CSTs and/or SBs whether an applicant has the achievement necessary for a high school diploma. Once one has that comparability data, then there is no need to administer CAHSEE to kids who meet the CAHSEE requirement before grade 10 . . . . saves a bunch of testing time and CA taxpayer money.

Gary Ravani 10 years ago10 years ago

"Graduation rates for low-achieving minority students and girls have fallen nearly 20 percentage points since California implemented a law requiring high school students to pass exit exams in order to graduate, according to a new Stanford study. The new study said that the exit exam, which is first given in 10th grade to help identify students who are struggling academically and need additional instruction to pass the test, has failed to meet one of its primary … Read More

“Graduation rates for low-achieving minority students and girls have fallen nearly 20 percentage points since California implemented a law requiring high school students to pass exit exams in order to graduate, according to a new Stanford study.

The new study said that the exit exam, which is first given in 10th grade to help identify students who are struggling academically and need additional instruction to pass the test, has failed to meet one of its primary goals: to significantly improve student achievement.

The study also said the exam is not a fair assessment of the basic skill levels of minority students and girls, because it takes higher skill levels for them to pass the test.”

Quote from article on report from Stanford Institute for Research on Education Policy and Practice: Prof. Sean Reardon lead investigator

Doug McRae 10 years ago10 years ago

The CAHSEE high school graduation requirement was authorized 15 years ago to install a statewide minimum standard for a high school diploma in California, in the context of widely varying standards used by individual schools and districts across the state. It has, by and large, done the job it was intended to do. In the very early 2000's, I recollect a brief exchange at the State Board of Education meeting, when the co-chair of a … Read More

The CAHSEE high school graduation requirement was authorized 15 years ago to install a statewide minimum standard for a high school diploma in California, in the context of widely varying standards used by individual schools and districts across the state. It has, by and large, done the job it was intended to do. In the very early 2000’s, I recollect a brief exchange at the State Board of Education meeting, when the co-chair of a CAHSEE Task Force (the Supt of Glendale Unified at the time) was asked a question on how the new 1997 academic standards were being implemented across the state . . . . his answer was “In elementary schools, implementation was going well; in middle schools, implementation was mixed but there were pockets of real progress; at high schools, it has been hard to move a cemetery!” I think CAHSEE has been one of the major reasons there has been some movement on academic achievement at the high school level in California, not for middle-of-the-pack kids or high flyers, but rather to insure some sort of minimal achievement is associated with a California high school diploma.

As said in the post, the Smarter Balanced tests are not being designed as minimum standards tests but rather as college/career ready tests. I’d agree with the comments from those with experience on this topic that SB grade 11 tests are not likely to replace the CAHSEE minimum standard purpose. Even adaptive testing will not have the range to measure minimum academic skills needed for a high school diploma, that’s just not in the cards. But that’s not to say that Smarter Balanced tests cannot be used to make the CAHSEE function more efficient — Smarter Balanced tests at the middle school grade range [which functionally measure the minimal achievement level needed for a high school diploma, per CAHSEE] can be used to pre-qualify students for the CAHSEE high school graduation requirement, and reduce actual high school graduation testing by 70-80 percent in the high school grades. Actually, the CAHSEE statute from back in 1999 anticipated alternative measures would be utilized rather than a one-size-fits-all 100 percent administration of CAHSEE to grade 10 students, but the previous and current SSPIs and the SBE over time simply haven’t been open to implementing this kind of common sense efficiency for the CAHSEE program.

Michele’s post briefly mentions CAHSEE waivers for students with disabilities. We actually have had two such waivers approved by the SBE, one back in the early 2000’s allowing accommodations and modifications in IEPs to be used without penalizing kids, and a recent waiver using STAR tests instead of CAHSEE that evaporated when STAR was discontinued in 2013. But, a fair number of students with disabilities currently are exempt from the CAHSEE graduation requirement, providing a loophole from the CAHSEE requirement. This loophole really isn’t justified, and SB 267 now on the Governor’s desk continues it indefinitely. AB 267 should be vetoed.

Joe Casarez 10 years ago10 years ago

Another variable to keep in mind is that the new assessment system is only scheduled to assess high school students in their junior year. Although I am concerned about having an assessment like the CAHSEE based on the former ELA and Math standards, I would be even more concerned by creating a system whereby high school students have only one opportunity to pass this high stakes assessment to earn a diploma.

john mockler 10 years ago10 years ago

Michelle Let us be clear. California students did not “pilot” test this year. There was no test of a test. There were 25 items in the math and 25 items in reading that may or may not be used in creating a future test. Smarter Balance did not give the state a test. They gave them items to test out. Much misunderstood and misreported issue.

Replies

Doug McRae 10 years ago10 years ago

I agree with Mockler. The 2014 Smarter Balanced exercise was an "item-tryout" in test development parlance, not a full test of an actual final test. CA kids won't see an actual Smarter Balanced computer-adaptive test until spring 2015. Further, according to Smarter Balanced Ex Dir Joe Willhoft at the State Board meeting early September, Smarter Balanced was not able to generate a full computer-adaptive item bank using federal funds the past four years, and still … Read More

I agree with Mockler. The 2014 Smarter Balanced exercise was an “item-tryout” in test development parlance, not a full test of an actual final test. CA kids won’t see an actual Smarter Balanced computer-adaptive test until spring 2015. Further, according to Smarter Balanced Ex Dir Joe Willhoft at the State Board meeting early September, Smarter Balanced was not able to generate a full computer-adaptive item bank using federal funds the past four years, and still needs to develop additional items to “fill in the holes” using UCLA-SBAC fees paid by states going forward, and will delay availability of their promised interim tests since they do not have enough qualified items to fill the interim testing item banks to release a full interim test package for the entire 2014-15 school year — rather, they hope to release one version of interim tests (complete tests mirroring final summative tests, a version that is controversial since it can be used to directly teach-to-the-test) in December while the other version (block tests focusing on selected content clusters, more useful for instructional purposes) will dribble out as item volumes permit the rest of the 2014-15 school year, and again additional item development for interim tests will be needed via UCLA-SBAC state supported funding going forward. The bottom line is that Smarter Balanced is not delivering all of the test content promised under federal funding, and California will be paying larger test development dollars going forward than has been anticipated. Finally, the item-tryout data from 2014 will not be sufficient to developed valid cut scores in advance of spring 2015 tests — as indicated on the Smarter Balanced website, the cut score setting exercise based on 2014 data will only produce “preliminary” cut scores which then will need to be validated by 2015 data with valid cut scores not available until probably September 2015 at best. This means CA as the choice of producing invalid scores in a timely manner (within a few weeks of administering the tests) summer 2015 and then replacing those scores with valid scores several months later, a plan that has very limited appeal but is the current plan approved by the State Board last July; or, delaying availability of spring 2015 scores until fall 2015 (October or later) until validated cut scores can be used to produce valid scores.

Michelle Maitre 10 years ago10 years ago

Thanks for pointing this out. I re-read the story and realized I inadvertently dropped a sentence that clarifies the issue. I’ve revised the section for clarity. Thanks for your comments.

Frances O'Neill Zimmerman 10 years ago10 years ago

God love you for understanding one word of what you've "explained" here. But let me guess: you must be a testing expert. Could the California high school exit exam be up for grabs? I hope not. Tweaking details to correlate with new curriculum makes sense, but the exam itself should be retained. The high school exit exam that began in 1999 has intrinsic value and now enjoys a high pass-rate. It is a common democratic hurdle for all students; it … Read More

God love you for understanding one word of what you’ve “explained” here.

But let me guess: you must be a testing expert.

Could the California high school exit exam be up for grabs? I hope not.

Tweaking details to correlate with new curriculum makes sense, but the

exam itself should be retained.

The high school exit exam that began in 1999 has intrinsic value and now enjoys

a high pass-rate. It is a common democratic hurdle for all students;

it can be passed as early as 10th grade, so allows time for all students to prepare and

be successful by12th grade graduation; it is a universal rite of passage; passing it is a

benchmark accomplishment for every kid. Finally, the exit exam invests the California

high school diploma with an aura of seriousness and desirability that was distinctly

lacking before the mandate.

I hope the exit exam is retained.

Doug McRae 10 years ago10 years ago

Frances -- Sorry for getting into the test development weeds on you. Yup, I've spent 45 years involved with large scale tests for K-12 education, now retired and working for the AARP [Am Assoc Retired Psychometricians] (grin). Computer-adaptive tests are sexy stuff with lots of glitzy promise, but one weedy aspect of them is they require a whole lot more qualified test questions than tests that just administer the same set of items to … Read More

Frances — Sorry for getting into the test development weeds on you. Yup, I’ve spent 45 years involved with large scale tests for K-12 education, now retired and working for the AARP [Am Assoc Retired Psychometricians] (grin). Computer-adaptive tests are sexy stuff with lots of glitzy promise, but one weedy aspect of them is they require a whole lot more qualified test questions than tests that just administer the same set of items to all kids. What my comment attempted to say was that Smarter Balanced has had difficulty developing a sufficient number of qualified test questions with their 4-year fed funding to fully implement summative and interim tests for their client states in the 2014-15 school year. Mockler ain’t a psychometrician, but he had enough experience with test development as Ex Dir SBE and Sec Educ in the early 00’s to understand the difference between the item-tryout stage of test development when the developer is just accumulating an adequate number of qualified test questions to build a full test, and the scoring rules stage of test development when a full final test is given to generate the appropriate data to established credible scoring rules (or “cut scores”). Smarter Balanced’s spring 2015 tests will be the scoring rules stage of test development, rather than fully operational tests as claimed by SB advocates in California. We won’t be able to generate credible valid scores for spring 2015 SB test administration until fall 2015 . . . . . schools and the public should know this, but thus far CA K-12 education leaders have not acknowledged it. Doug

Barbara Inatsugu 10 years ago10 years ago

Thanks for the clarification, John. A needed one.

FloydThursby1941 10 years ago10 years ago

Let's be real here. Some kids have to fail to make passing the test meaningful in any way. The problem with this test is that everyone gets so upset about anyone failing they try to make it easier. You need a high school diploma to mean you have basic skills, not just that you benefited from social promotion. If no one fails, it's what it was before, an attendance certificate. … Read More

Let’s be real here. Some kids have to fail to make passing the test meaningful in any way. The problem with this test is that everyone gets so upset about anyone failing they try to make it easier. You need a high school diploma to mean you have basic skills, not just that you benefited from social promotion. If no one fails, it’s what it was before, an attendance certificate. Why does everyone feel so sorry for those who fail? They are kids studying 2 hours a week in high school most likely, never reading, and watching TV 40 hours a week. These people need to work harder if they want to pass. Some are immigrants, OK, you need to go to night school and learn fluent English.

I think they should publish your score. It shouldn’t just be pass and fail. For instance, if 70 is passing, some jobs should require 80, or 85, or 90. For instance, police officers are well paid so that should require 80 to eliminate those who slacked off in high school. Well paying jobs should be a reward for doing the moral thing in school, doing your homework, showing up, studying hard. We’ll get better effort in school if we strengthen this test and ask government employers to require higher than just passing scores. This will make a lot of kids work harder and help our standing against other nations by adding a key ingredient, motivation.