Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

The threatened deluge of post-pandemic special education litigation may be averted — or at least minimized— by a new initiative in California encouraging parents and schools to resolve disputes before heading to court.

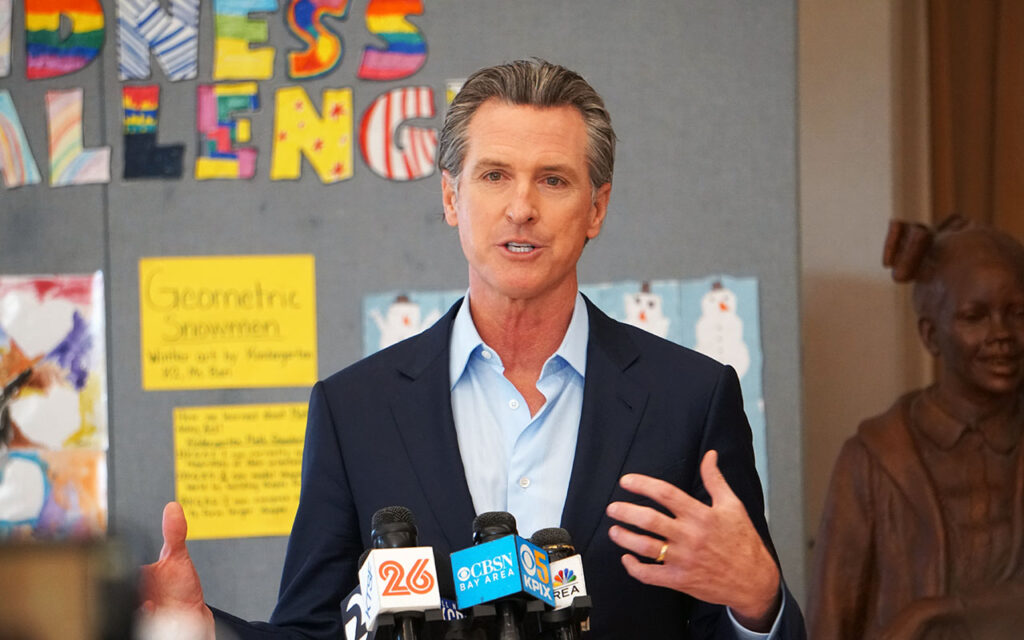

The state budget, signed Friday by Gov. Gavin Newsom, sets aside $100 million for resolving special education conflicts between parents and school districts, which escalated during remote learning.

The money will go toward outreach, such as brochures, meetings and presentations, to help parents and school staff understand the rights outlined in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the federal law that requires districts to educate students of all abilities. The goal is to improve communication and build trust between parents and schools, so conflicts can be resolved quickly and more easily.

None of the money can go to attorney fees.

“I had tears of joy when the governor signed it. We worked so hard to make this happen,” said Veronica Coates, director of Tehama County’s Special Education Local Plan Area, who helped craft the legislation. “We won’t escape all disputes, but this means we can devote more resources to helping kids, not paying lawyers.”

In addition, the state set aside $450 million for extra tutoring, therapy and other services that students with special needs missed during remote learning. It also funded the first steps of a system similar to what other states use to help parents get support from neutral facilitators during special ed meetings. The aim is for parents to better understand the special education process and needs of their children.

Many students in special education fell behind during distance learning because so many services for disabled students — such as speech or physical therapy — were nearly impossible to deliver virtually. Under federal law, parents can sue a school district if they feel their children aren’t receiving services they’re entitled to in their individualized education program, or IEP.

Special education lawsuits can be expensive for school districts. The cost of providing special services might be relatively minimal — say, a few thousand dollars — but if the district loses the case, it often owes parents for their attorney fees, which can top $100,000. The district also has to pay its own attorneys, although those costs are typically lower. In some cases, a judge orders districts to pay for costly services such as boarding school for students with severe challenges.

Schools in California have so far paid more than $5.4 million in attorney fees for Covid-related special education disputes, Coates said, adding that the number is probably far higher because only a quarter of districts responded to a survey on the topic. Less than half that total — $2.3 million — went to providing services to students in those disputes, she said.

Disputes usually center on the number of hours of extra services a student might need. A district might say a student is entitled to two hours a week of speech therapy, for example, but a parent might want eight. If the parties can’t compromise, either side has the option of requesting a hearing with the state Office of Administrative Hearings. The department assigns a mediator to help the parties resolve the matter, and if that fails an administrative law judge will hear the case.

California sees far more special education disputes, on average, than most other states. In 2018-19, parents’ requests for mediation in California represented nearly half of the requests nationwide, according to the Consortium for Appropriate Dispute Resolution in Special Education. California’s rate of mediation requests was four times higher than the national average. The number of cases in California jumped 84% from 2006-07 to 2016-17, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, costing schools millions.

Last year, the number of cases filed with the Office of Administrative Hearings actually fell 16%, according to the department, although that number may increase this fall as schools get caught up with student assessments and evaluations. In 2020-21, when most schools were closed due to Covid-19, the Office of Administrative Hearings received 3,908 cases, 87 of which couldn’t be resolved through mediation and ended up in court. The previous year, the office received 4,650 cases and held 91 hearings.

Many of the cases post-pandemic are centered on “compensatory education” — extra services to help students catch up to the benchmarks in their IEPs. Compensatory education can mean one-on-one tutoring, summer or after-school programs, extra therapy or other specialized assistance.

Matthew Tamel, a Berkeley attorney who represents school districts, said so far his volume of special education cases hasn’t increased since the pandemic, but “the cases are more intense, harder to settle.” They often center on what services a student needs to catch up following campus closures. A parent might want 400 hours of speech therapy for their child, for example, while the district believes the actual estimate of lost time is closer to 100 hours.

State funding to help resolve these disputes before they head to court is a welcome development that will hopefully lead to smoother negotiations and outcomes that are reasonable for both sides and beneficial for students, Tamel said.

“When schools first closed, it was a very difficult time. Everyone thought it would just be a few weeks, and it turned into a year and a half in some districts. Not everything was perfect when schools first closed,” he said. “Most families understand that. … This fund will hopefully help students get the services they need to make up what was missed in 2020 without having to go to court.”

But some say the state’s promotion of out-of-court dispute resolution favors districts, not parents. Without hiring lawyers or professional advocates, parents might be at a disadvantage when negotiating with districts over the services they believe their children need. Lower-income parents are especially vulnerable because the only way they can get reimbursed for attorney fees, which can cost upwards of $400 an hour, is by going to court, said Jim Peters, a Newport Beach advocate who helps parents in special education disputes.

“I support the idea in general of alternative dispute resolution, but in this case it’s disingenuous,” said Peters, who helped organize a class-action special education lawsuit against the state last year. “The money won’t be given out based on a child’s needs, it’ll be given out based on which parents can afford to hire attorneys.”

Angelica Ruiz, a parent in San Bernardino County whose 12-year-old son, Arthur, has moderate-to-severe autism, said she never would have won extra services for her son if she didn’t have a professional like Peters advocating on her son’s behalf.

Courtesy Angelica Ruiz

Angelica Ruiz and her son, Arthur.

During remote learning, Arthur suffered anxiety and behavior meltdowns as the pandemic wore on. He’d often refuse to participate in online classes. He began hitting himself, his personal hygiene declined and he suffered from severe insomnia, Ruiz said.

Peters helped her son get extra therapy and other services, she said. It didn’t solve everything, but it made a big difference for Arthur, she said.

“Sitting in a room with all these people from the school, it can be intimidating,” she said, describing her meetings with her son’s teachers, therapists and school administrators. “Most parents aren’t trained to do this, we don’t always know what we’re entitled to or what we should be asking. … Parents should not have to file (a suit) just to get the services their kids need. We shouldn’t have to fight over it.”

But solving conflicts like Ruiz’s is exactly what the new state fund will do, said Coates, the special education director from Tehama County, and Anjanette Pelletier, special education director for San Mateo County. By minimizing the role of attorneys and advocates, parents of all incomes should have access to fair, free dispute resolution. And disputes will be settled quicker, allowing students to receive services sooner, they said.

Pelletier and Coates began working on the legislation a year ago, when they noticed a sharp uptick in litigation in their counties related to special education during campus closures. The lawsuits not only delayed districts from providing services to students, but they also generated mistrust and antagonism between families and school staff, they said.

“Schools were in a bind,” Coates said. “This was born out of a need to help our students get services faster, and improve relationships with families.”

Another issue is the ongoing shortage of special education teachers, worsened by the pandemic, Coates and Pelletier said. Special ed teachers are already facing high levels of stress trying to help students during Covid; they don’t need the additional stress of litigation, they said.

Working with Assemblyman Jim Frazier, D-Fairfield, and others, the pair helped create the legislation and shepherded it through the budget process. Ideally, the $100 million for outreach will benefit not just families but school administrators as well, they said.

“That’s the dream, that administrators learn to improve communication with all families,” Pelletier said. “We’re not going to get rid of all disputes, but hopefully this will allow us to do what’s best for kids and spread the resources more equitably.”

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (11)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Alan 8 months ago8 months ago

School districts in California defund special education by not hiring teachers and para-educators. They drag their feet and don’t start the process until parents complain. Superintendents often transfer money from special education to their general fund. Keeping special education in a broken state with low salaries and poor district management allows superintendents to fund their pet projects on the backs of the most needy.

Kay 1 year ago1 year ago

My daughter has suffered deliberate willingness to ignore her need for special education support. It’s amazing how Fresno Unified is only willing to assist 2 years while they have neglected a special needs child for 4 years with knowledge of the needs.

Qtips 2 years ago2 years ago

The Special Education system needs reform. There seems to be this notion that schools are out to deny services to students with special needs. I've worked in many different classrooms over the years and can tell you that most every teacher, specialist and administrator has their heart in the right place and wants what's best for their students. However, oftentimes the requests of these families are unwarranted and frankly disrespectful of the opinions of the … Read More

The Special Education system needs reform.

There seems to be this notion that schools are out to deny services to students with special needs. I’ve worked in many different classrooms over the years and can tell you that most every teacher, specialist and administrator has their heart in the right place and wants what’s best for their students. However, oftentimes the requests of these families are unwarranted and frankly disrespectful of the opinions of the specialists.

Let’s say that a student receives an hour of speech therapy in kindergarten. Now let’s say that by third grade, the speech language pathologist (SLP) suggests that the student’s speech is functional and that they no longer require the service. In theory, parents can continue to sign on for this service against the SLP’s recommendations until the child is 22 and the school can take no recourse.

Last week we received an assessment request for a student in all areas of disability – psychological, academic, speech, fine motor and gross motor. However, the only reported area of need by the IEP team was reading. Parents insisted on testing in all areas (a process that takes 8-10 hours per specialist) just to “rule out” despite the fact the professionals insisted that the student should only be tested in areas of suspected disability.

At my district, we receive referrals every day regarding everything from the student having anxiety to the student not liking showering at home to observations made by private doctors who do not see the child regularly and base their findings on a one-time assessment.

I think we tend to think that children with disabilities and their families are always underdogs but the truth is that the system is abused both ways. No, schools do not always demonstrate competence and efficiency (this is mainly a result of high stress-related turnover and a crushing amount of paperwork, particularly in Special Ed). That being said, there are definitely parents who use the system as a means of obtaining free ongoing support for their children without understanding the IEP process or respecting the professional opinions of the staff that is providing education to their child.

Dawn 3 years ago3 years ago

I have a grandson who is is in this very predicament. I am so happy to read that something is being done about it!

Pat 3 years ago3 years ago

I don't know how practical this would be from a financial aspect, but I would like to see an advocate assigned to a family going through this process w/o charge. If they are knowledgeable about what their child needs, then they can decline the advice. This would encourage a family not to go to court, and sounds cheaper in the long run for the school district. It would attain the needed services faster, and … Read More

I don’t know how practical this would be from a financial aspect, but I would like to see an advocate assigned to a family going through this process w/o charge. If they are knowledgeable about what their child needs, then they can decline the advice. This would encourage a family not to go to court, and sounds cheaper in the long run for the school district. It would attain the needed services faster, and give the family something that they currently have to go to court in order to be reimbursed.

Heather Zakson 3 years ago3 years ago

I'm curious to know if you independently checked Ms. Coates' sources. $5.4 million in attorneys fees and $2.3 million in services for kids? It would be helpful to know where those figures came from. A quick search through the Office of Administrative Hearings reveals that Tehama County has not been in court over a special education dispute since 2010 - and in that case, Tehama sued the disabled child's parents, not the other … Read More

I’m curious to know if you independently checked Ms. Coates’ sources. $5.4 million in attorneys fees and $2.3 million in services for kids? It would be helpful to know where those figures came from. A quick search through the Office of Administrative Hearings reveals that Tehama County has not been in court over a special education dispute since 2010 – and in that case, Tehama sued the disabled child’s parents, not the other way around.

There’s nothing wrong with alternative dispute resolution – the vast majority of special education disputes are resolved through some kind of mediation and negotiation process and never reach trial. Special education attorneys know that’s a great way to get children the support they need.

Unfortunately, Ms. Coates might have another agenda.

Frank 3 years ago3 years ago

We have a global pandemic, and we're blaming schools for not providing extra services? No kidding, schools aren't offering the same services to students. They're restricted by the worldwide disaster we're in. Anyone who yells and screams will probably get what they want. But, that doesn't mean they should. They definitely shouldn't during the hell that everyone's been through. Read More

We have a global pandemic, and we’re blaming schools for not providing extra services? No kidding, schools aren’t offering the same services to students. They’re restricted by the worldwide disaster we’re in. Anyone who yells and screams will probably get what they want. But, that doesn’t mean they should. They definitely shouldn’t during the hell that everyone’s been through.

Replies

Christopher A Rosa 3 years ago3 years ago

And what about all the parents and students who were ignored and not addressed by the decision makers in the district? That’s the real reason behind the lawsuits. The districts failed many families. It’s the same story with any patent you speak to. They never called me or emailed me back? I didn’t know what else to do. So I brought or joined a lawsuit.

Frank 3 years ago3 years ago

It's hard for me to imagine employees of a district who are purposely trying to block a student from their services. They might be incompetent, they might not have enough time or other resources, but they don't likely benefit from acting to the detriment of a student. Parents face the same deficiencies, but how many districts use aggressive legal strategies to control the parent? Like everything, relationships matter. If an IEP team has a weak … Read More

It’s hard for me to imagine employees of a district who are purposely trying to block a student from their services. They might be incompetent, they might not have enough time or other resources, but they don’t likely benefit from acting to the detriment of a student. Parents face the same deficiencies, but how many districts use aggressive legal strategies to control the parent? Like everything, relationships matter. If an IEP team has a weak relationship where they don’t communicate, then there is a need for the members to come up with a solution, and I’m not sure lawsuits are the best way in many cases.

For me, it would take a ton to join a lawsuit. There’s too much money involved, and it can destroy the morale of an IEP team.

That being said, if I had your experiences with the particular districts in your life, I might agree with you, and if you’ve decided on pursuing a lawsuit, I hope you win.

Robert D. Skeels, JD, Esq 3 years ago3 years ago

To the extent that this provides families of students with disabilities another avenue to secure their rights, I applaud this. In the rare case that schools are actually operating in good faith, this will speed up access to services for students that need them most. However, for all the charter school corporations and public schools that will use this to deprive students of their educational rights, there's this: Gov. Code § 56845.9(a) "This article shall not be … Read More

To the extent that this provides families of students with disabilities another avenue to secure their rights, I applaud this. In the rare case that schools are actually operating in good faith, this will speed up access to services for students that need them most.

However, for all the charter school corporations and public schools that will use this to deprive students of their educational rights, there’s this:

Gov. Code § 56845.9(a) “This article shall not be construed to… [a]bridge any right granted to a parent under state or federal law, including, but not limited to, the procedural safeguards established pursuant to Section 1415 of Title 20 of the Unites States Code.”

As for Veronica Coates seemingly seething resentment towards attorneys working hard to help children with disabilities obtain their rights, she should consider the fact that if schools would merely follow the law, there’d be no need to file for Due Process.

Robert Bartlett 3 years ago3 years ago

The best response to the increase in litigation would be to get students back to in-person learning. Last year (2020-2021), many parents were shocked by their student's behavior at home during remote learning. They couldn't believe how defiant they were. In addition, many students with learning handicaps struggled to comprehend the delivery methods of online instruction. It was overly visual, with almost no interaction with the teacher. To compensate, students would try to enlist their … Read More

The best response to the increase in litigation would be to get students back to in-person learning. Last year (2020-2021), many parents were shocked by their student’s behavior at home during remote learning. They couldn’t believe how defiant they were. In addition, many students with learning handicaps struggled to comprehend the delivery methods of online instruction. It was overly visual, with almost no interaction with the teacher. To compensate, students would try to enlist their parents as a substitute for the role of teacher.

Parents are trying to shield themselves from their child’s demands. Extra services means extra time with a teacher supervising the child in a one-on-one situation as opposed to the parent providing the one-on-one supervision. Not all the litigation is in good faith. Some of it is parents avoiding the demands of the pandemic. They’re grabbing for resources more than trying to help their child “catch up.” There is very little evidence to support the idea of catching up in tutoring sessions. For instance, what standards and methods will these tutoring sessions follow? “Catching up” is a hackneyed catch phrase for parents who want to stop being a free tutor. Some parents just can’t see the civic duty in it. Bring all special-ed students back to full-time in-person learning immediately, without regard for other precautions.

Spend all the money on hiring whatever staff it takes, especially paraeducators. If that commitment is made, the litigation will cease. Relieve parents of the burden of tutoring their students, at least full-time tutoring. That will minimize regression, which is a better promise than “catching up.” The goal now is it stop regression and to stop it quickly, and the only way to do that is with full-time in-person learning.