Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

California policymakers say they intend to create a different system for reporting results of the upcoming tests on the Common Core standards than parents and schools have become used to in the era of the No Child Left Behind Act.

At this point, they can’t say what it will look like. The reporting system is one of several moving parts that include recalibrating the Academic Performance Index, the current measure of school improvement, of which the results on the Common Core standards would be a big piece. But state leaders can say what the new system won’t be: anything resembling the federal system for measuring schools, which led to most being judged failures.

“States can report however we want and can include anything that we want,” said Michael Kirst, president of the State Board of Education, which is immersed in creating a new accountability system for districts and schools.

California education officials spent several days last month with their counterparts from the 22 member states in the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium deciding how to place students’ scores into bands of achievement on the new Common Core tests they will be giving next year. But state policymakers are distancing themselves from what they agreed to and say they plan to create a better way to present scores to parents and to judge schools’ and districts’ progress.

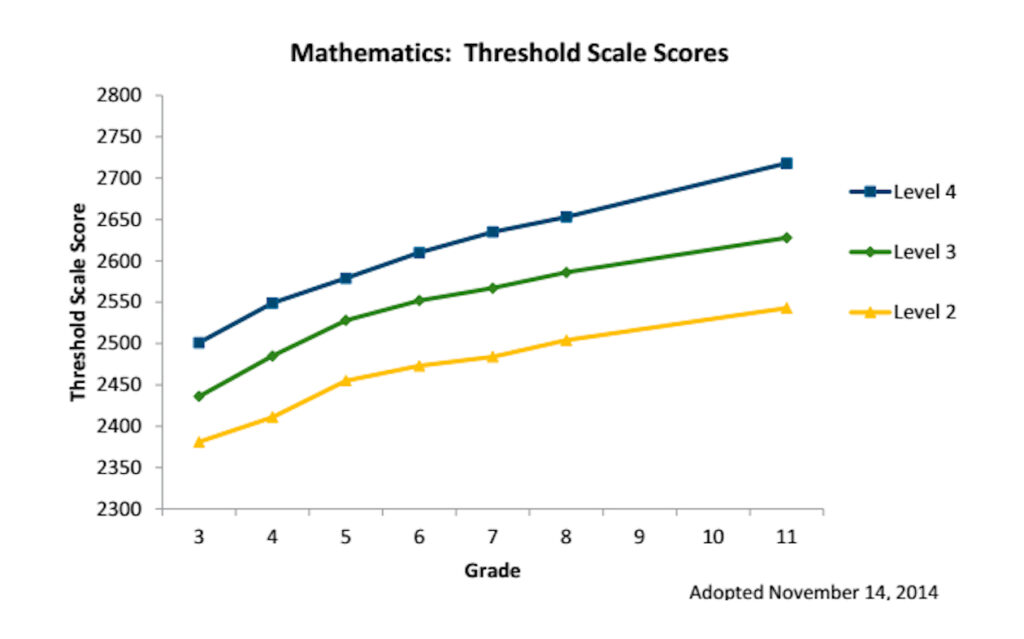

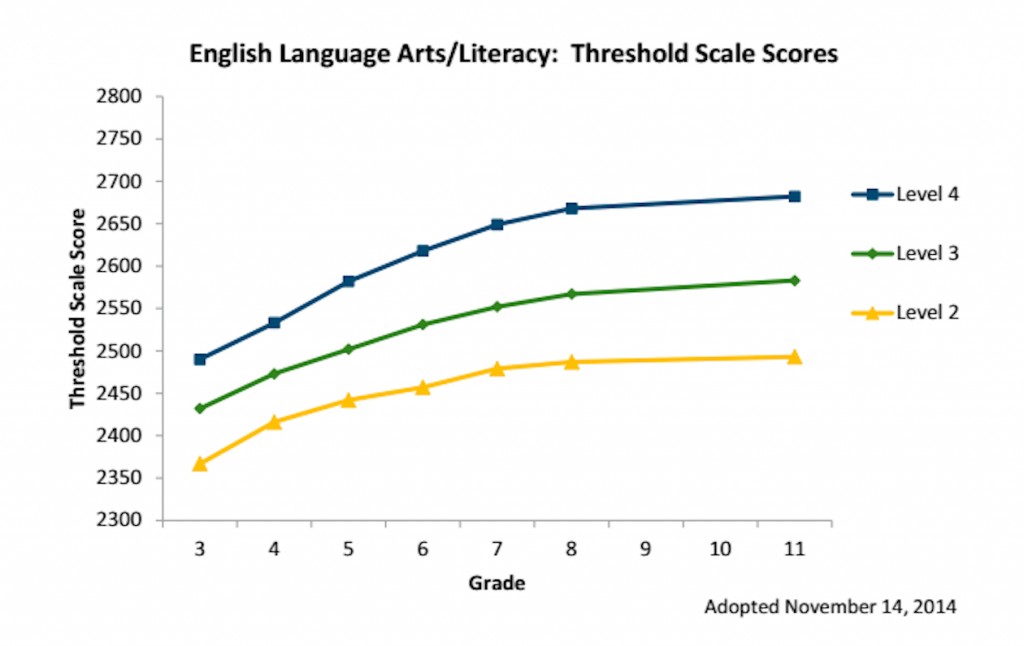

The Smarter Balanced representatives approved “cut scores” for the new tests. The scores are single points that divide the spectrum of test scores into four achievement levels, from the lowest, Level 1, to the highest, Level 4, indicating degrees of mastery of Common Core content. That approach is similar to what California and other states have done in the past and conforms with the requirements of No Child Left Behind, which has mandated that all states report annually how many students’ standardized test results in grades 3 to 8 and grade 11 fall within each level. The federal government has penalized schools whose students failed to score at least at Level 3 – defined in past tests as proficiency – in English language arts and math. Though much criticized and all but discredited, NCLB remains the law of the land.

Source: Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium

The thresholds for achievement levels, known as cut scores, on the Smarter Balanced tests were based on the judgments of teams of educators at each grade, then aligned for inter-grade consistency and adjusted to reflect how well students did on the field tests last spring. Smarter Balanced estimates that less than half of students – closer to a third in some grades – will score at Level 3 next spring, the first administration of the official tests. This graph shows the achievement levels for English language arts.

Some Smarter Balanced states chafed at continuing the NCLB model. Vermont and New Hampshire abstained from the consensus vote to approve the cut scores.

Vermont’s secretary of education, Rebecca Holcombe, wrote a three-page letter that said the use of cut scores “misrepresents the underlying complexity of achievement and contributes to simplistic policies that make it difficult to achieve our public purposes.”

Kirst, who wasn’t at the meeting but participated in discussions with the state’s delegation*, said California leaders share Holcombe’s concern, but since they represent the largest state and are a driving force in the consortium, they didn’t want to abstain. Instead, California pressed member states to adopt a memorandum that was released with the cut scores. It reiterated some of Holcombe’s arguments with the admonition that cut scores and achievement categories “should serve only as a starting point for discussion” about student achievement and “should not be interpreted as infallible predictors of students’ futures.” Californians, including Stanford School of Education professor Linda Darling-Hammond, a technical adviser to the Smarter Balanced consortium, had a major hand in drafting the memo.

Creating categories to designate proficient and basic levels of performance, as NCLB requires, “has a public appeal” because it enables clear comparisons and can highlight achievement gaps among student groups, Holcombe acknowledged in her letter. But using a single point on a standardized test to set the levels, Darling-Hammond argues, is “a crude measure” and arbitrary. “A cut score has had a magic quality, yet is not as precise as numbers would lead you to believe,” she said.

Under NCLB, cut scores “led to dysfunctional behavior” in which school districts focused their attention on “bubble kids” – raising scores of those right below the cut score while ignoring those further below or above the line, she said. Schools would not get credit when students showed growth within achievement levels from year to year or when scores grew significantly but fell short of proficient.

The Common Core standards, most agree, are not only different from but also more challenging than those in most states, including California’s previous standards. As a result, state officials have repeatedly warned against comparing scores and achievement levels on Smarter Balanced tests with past states’ tests. To discourage comparisons, the Smarter Balanced consortium has avoided labeling Levels 1 to 4 as below basic, basic, proficient and advanced.

Kirst also said that technically, Smarter Balanced Level 3 does not designate that a student is performing at grade level. For 11th grade, Level 3 will signal much higher achievement, that a student is on track by the end of high school for coursework at a four-year college without the need for brush-up courses or remediation. California had lobbied for that rigorous definition of Level 3 as a potential replacement for the Early Assessment Program, which the California State University created a decade ago as a supplement to the 11th-grade state standardized tests.**

Since Smarter Balanced’s Level 3 would set a standard higher than proficiency, Kirst said, scoring below it doesn’t mean a student is doing subpar high school work or is not prepared for a two-year associate’s degree or entry into a training program to become, say, an electrician or dental hygienist. California may set separate cut scores for the high school exit exam or readiness for various post-secondary career paths, he said. The Advisory Committee for the Public School Accountability Act, which reports to the state board, will discuss various possibilities, he said.

Students who take the Smarter Balanced tests next spring will receive a four-digit score on a scale of 2,000 to 3,000, a point system intentionally chosen to differentiate it from what other states have used. Unlike the old California Standards Tests, the Smarter Balanced tests are designed to be scored on a continuum from grade to grade. This vertical alignment from 3rd- to 11th-grade tests is critical, because it will make it possible to track the progress of individual students and subgroups of students in mastering the Common Core over time.

Holcombe’s letter encourages states to report students’ scale scores, with attention to gains from year to year, instead of focusing on percentages of students who score within the different achievement levels. Kirst and Darling-Hammond say they favor that as well.

And instead of using single cut scores, they advocate reporting scores in what are called confidence bands, a score range that recognizes that cut scores are approximations of student knowledge. Confidence bands are like the margins of error that pollsters use when reporting voter surveys.

Doug McRae, a retired educational testing company executive who was in charge of designing and developing K-12 standardized tests, agrees with Kirst and Darling-Hammond. McRae has been an outspoken critic of the process that Smarter Balanced used in creating achievement levels (see his EdSource commentary) and the lack of openness in explaining how exactly the cut scores were determined, then modified based on the results of the Smarter Balanced field tests last spring.

“If California’s goal is to go to scale scores and report scores in ranges rather than achievement categories, from a purist perspective, I agree,” he said. “It is better in terms of reducing the overinterpretation of scores. This has also been the goal of K-12 test publishers for the last 40 years, but has never materialized.”

Kirst said that the state board will spend the next 10 months revising the state’s school accountability system. The key date is Oct. 15, 2015, when California law requires the state board to have adopted a set of “rubrics” or rules for measuring state and local goals in district Local Control Accountability Plans. Measures of academic progress are only one of eight requirements in the plans, and state standardized tests are just one indicator within that requirement.

Before then, however, the state board must decide how to present next spring’s Smarter Balanced test results to parents and schools. That message will likely be: Consider the scores a useful first-year indicator but not the preeminent measure of achievement on the new standards or readiness for college.

* Members of the state delegation included Rich Zeiger, chief deputy state superintendent; Karen Stapf Walters, executive director of the State Board of Education, and Diane Hernandez, director of the California Department of Education Assessment Development and Administration Division. Deb Sigman, a former state deputy superintendent who is now a deputy superintendent in Rocklin Unified School District, and Keric Ashley, interim Deputy Superintendent of Public Instruction of the state Department of Education, didn’t attend the achievement-level setting meeting but have represented the state previously. Beverly L. Young, assistant vice chancellor for academic affairs, California State University, is a member of Smarter Balanced’s executive committee.

** An earlier version of the article incorrectly stated that the University of California campuses recognize results of the Early Assessment Program for placement in non-remedial courses. Only CSU and many community colleges do. In the same paragraph, the definition of Level 3 in 11th grade has been clarified.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (11)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Don 9 years ago9 years ago

"That message will likely be: Consider the scores a useful first-year indicator but not the preeminent measure of achievement on the new standards or readiness for college." Can I take this last sentence from John's article to mean that reporting of results will change after the first year? This does not engender public confidence in the reporting process. It looks like spinning the results. If they want to get rid of achievement categories and … Read More

“That message will likely be: Consider the scores a useful first-year indicator but not the preeminent measure of achievement on the new standards or readiness for college.”

Can I take this last sentence from John’s article to mean that reporting of results will change after the first year? This does not engender public confidence in the reporting process. It looks like spinning the results. If they want to get rid of achievement categories and cut scores, do it from the get-go.

People may be accustomed to achievement bands or ABCDF grades that are by definition distinct from one another, but these are results for people who want them “at a glance”. What would be valuable for assessment and instructional purposes would be a breakdown of how students perform in specific content areas – a result which could easily be computer-generated for reporting to families. Since achievement bands are related to overall school performance non-waivered states like California under NCLB could still be used for that purpose but go unreported for individual students. Scale scores should be implemented and SBAC should not lose this opportunity after all these years.

Doug McRae 9 years ago9 years ago

"Ms. Flowers, my daughter's score was 2518 on the new Smarter Balanced math test. What does 2518 mean?" Whether or not a plan to use scale scores and confidence bands to report Smarter Balanced test results will work depends largely on whether teachers can explain the "new" scores to parents and students . . . . Growth scores (or the usual technical term "vertical scale scores") were introduced to K-12 national tests in 1964 via … Read More

“Ms. Flowers, my daughter’s score was 2518 on the new Smarter Balanced math test. What does 2518 mean?”

Whether or not a plan to use scale scores and confidence bands to report Smarter Balanced test results will work depends largely on whether teachers can explain the “new” scores to parents and students . . . .

Growth scores (or the usual technical term “vertical scale scores”) were introduced to K-12 national tests in 1964 via the SRA Achievement Series tests, and were part of the statistical framework for all widely used national normative tests within 5 to 10 years. When the country converted from primarily normative tests to state-by-state standards-based tests in the late 90’s and early 00’s, about half of the states included vertical or growth scores in their statewide testing systems. CA’s STAR CST’s were among the statewide tests that did not have growth or vertical scale scores. But, there have been many efforts to introduce growth scores and confidence bands as commonly accepted lexicon for K-12 tests over the past 50 years, all with limited success due to the communication challenges at the basic teacher/parent/student level . . . .

Quantitative types almost universally agree use of strong growth or vertical scales with confidence bands [note -- whether the new Smarter Balanced growth scores are strong scales or don't hold water is yet to be determined] would improve K-12 large scale testing practices in the US considerably, including reduction of misinterpretations and misuse. Making this happen at the basic communication level involving teachers and parents and students is easier said than done.

The primary large scale testing systems in the US that do use scale scores for reporting are the SAT and ACT college entrance tests. Those systems are not growth or vertical scales, and the public lexicon for these tests typically does not include confidence band reporting. Outside of educational tests, as John notes, use of confidence band reporting for political polling is a primary example of a quantitative success story for introducing more accurate reporting practices for widespread public use; this practice was introduced by national TV networks for the 1968 election. But it took until the 1980’s for it to take root as accepted practice for forecasting election night returns, and then it survived a near meltdown in 2000 with the Bush-Gore premature forecasts on election night.

It’s great that CA K-12 education leaders are forward looking on the score reporting issue . . . . maybe this time around will be the charm.

Replies

FloydThursby1941 9 years ago9 years ago

They really should report Percentiles on every score, even if it is a range. It is valuable to know your child is at the 91st percentile or 9th, or 99th or 50th. You probably need to be in the top 10% to go to a UC with so many of the other 2.5% going to international and out of state residents because they pay more money, so knowing percentiles will spur parents and kids … Read More

They really should report Percentiles on every score, even if it is a range. It is valuable to know your child is at the 91st percentile or 9th, or 99th or 50th. You probably need to be in the top 10% to go to a UC with so many of the other 2.5% going to international and out of state residents because they pay more money, so knowing percentiles will spur parents and kids to work harder. Vague scores make people feel they’re doing well enough and discourage harder work. It’s best to get scores after 2d grade, as if you get tutors and Kumon and prioritize education over all else in a family at that age if they are behind, you can still turn things around. I see all the info about adult education, but really at a certain point it is too late to be a great student. We need testing and adjustments to work ethic made as early as possible and families to put as much emphasis on education as possible.

Kelly 9 years ago9 years ago

How can the Smarter Balance tests be standardized? This is an adaptive test, meaning when you answer the question correctly you then will get a harder question, and when you answer incorrectly, you will get an easier question. It would seem all students take a "different" test, which is not the definition of standardized. Add to this, "cut" scores, which are decided by the states. So, parents will have NO idea … Read More

How can the Smarter Balance tests be standardized? This is an adaptive test, meaning when you answer the question correctly you then will get a harder question, and when you answer incorrectly, you will get an easier question. It would seem all students take a “different” test, which is not the definition of standardized. Add to this, “cut” scores, which are decided by the states. So, parents will have NO idea how their child has actually done because the scores are manipulated from state to state every year. So, initially, the states will raise the cut scores to let parents know how much Common Core is needed, and then after a few years to make the kids look smarter they will lower the cut scores, and wow…common core must work. No thanks, I’ve opted my kids out of the tests and test prep. OPT OUT and have teachers get back to teaching, not test prep!

Replies

Doug McRae 9 years ago9 years ago

Kelly -- Three points: First, "standardized" tests refer to all students taking the same testing exercise, not necessarily exactly the exact same test questions. Smarter Balanced computer-adaptive testing schemes fit the definition of a standardized testing practice. Second, cut scores for the new consortium tests (PARCC as well as Smarter Balanced) are ultimately set by each state, but once they are set they DO NOT change from year-to-year. The goal is to measure change over time, and … Read More

Kelly — Three points:

First, “standardized” tests refer to all students taking the same testing exercise, not necessarily exactly the exact same test questions. Smarter Balanced computer-adaptive testing schemes fit the definition of a standardized testing practice.

Second, cut scores for the new consortium tests (PARCC as well as Smarter Balanced) are ultimately set by each state, but once they are set they DO NOT change from year-to-year. The goal is to measure change over time, and to measure change one cannot change the measure. Changing cut scores would change the measure, which would invalidate the measurement of change over time, just like wholesale changes to the test items that are administered would invalidate the measurement of change over time. [Small adjustments are permitted to accommodate replacement of some items that are retired from the active test item banks used for large scale tests, but these small adjustments are strictly limited by statistical methods (called “equating” studies) that do not involve judgments or manipulations by policymakers.]

Third, on opting-out, as a long-time K-12 test maker I’d DISCOURAGE opting out of large scale statewide tests, but I’d ENCOURAGE opting-out of extensive unwise test prep practices. One of the major flaws in the new Smarter Balanced overall system is a so-called “comprehensive” interim test version that is a clone for their end-of-year summative test, a tool that will promote unwise unethical test prep practices. It was poor judgment by Smarter Balanced to produce such a tool, and really poor public policy for the CDE/SSPI to recommend and the SBE to approve via regulation the availability of such an unethical test prep tool for CA schools. If any parent observes extensive use of the Smarter Balanced “comprehensive” interim test version [to be available January 2015 according to Smarter Balanced and CDE sources] to prep kids for spring 2015 Smarter Balanced summative tests, I’d encourage parents to blow the whistle and opt out of this kind of test prep. But, large scale statewide tests can and should provide good usable information for parents, and I’d discourage parents from opting out of the tests themselves.

Harold Capenter 9 years ago9 years ago

You know I just hate it when writers or commenters don’t check their facts. Actually Fordham rated California Standards Superior to the Common Core Standards. And, since, Fordham has financial backing from Gates, it makes the “superior rating” all the more powerful. Check it out – here is the link: http://edexcellencemedia.net/publications/2010/201007_state_education_standards_common_standards/California.pdf

navigio 9 years ago9 years ago

A few points.. "states can report however we want and can include anything we want." First it's important to recognize this reflects the fact that the SBAC performance bands are not binding. I think there will be pressure to use them, but we should strive for what makes sense, whatever that is. But I'd hope this statement is not an indication that any measures will be largely useless. We have to keep in mind why we want … Read More

A few points..

“states can report however we want and can include anything we want.”

First it’s important to recognize this reflects the fact that the SBAC performance bands are not binding. I think there will be pressure to use them, but we should strive for what makes sense, whatever that is.

But I’d hope this statement is not an indication that any measures will be largely useless. We have to keep in mind why we want a standardized accountability system. If we don’t use it for its intends purpose then we shouldn’t have it.

Cut scores are only magic because we treat them that way. If we continued to remind ourselves how variable results can actually be, we could have cut scores and not treat them as magic. Alas, the simple human wins thus loses..

IMHO, the API calculation intended to counter the ‘bubble kid’ effect. Not sure how well it achieved that.

The idea that we shouldn’t want to compare grade level performance across tests is ludicrous. If it’s invalid it can only be because the definition of grade level has actually changed. If so, that would be, um, like, important to know.

I’m flummoxed by Kirst’s statement on level 3 vs grade level. This seems to gloss over a critical point: that our current expectation is NOT grade level proficiency. And that that proficiency is NOT assumed to reflect a mastery of the minimum competences of the standard. The whole idea of a standard seems to be to define ongoing competency expectations (in a system that uses grades, this would map to grade level expectations). That said, his subsequent sentence seems to indicate that what this would mean is multiple versions of competency, based on multiple post secondary goals. While I agree this is much more beneficial than saying a kid is a success or a failure, I do think this change in approach needs to include what we consider grade level to mean.

The vertical scale score is one of the things Doug me tuned as necessary for evaluating teachers based on standardized tests. The article only mentions students and student subgroups. I really wish we could have a semi-technical discussion about vertical scales. And whether this would more easily allow us to do away with the traditional concept of grade (especially in how it applies to grade level standards).

A suggestion on what to provide: put it all out there and look at how people use it. 🙂

Robert Caveney 9 years ago9 years ago

Hi John, Thank you for this summary about the reporting. There is another report, which will likely continue as before, the internal benchmark tests which are conducted 2-4 times per year. These tests, designed by individual school districts, will continue as before. The heart of the school crisis is caused by this series of benchmark tests and the teaching schedule. Consider: (By they way, no less than John Merrow, education correspondent for … Read More

Hi John,

Thank you for this summary about the reporting.

There is another report, which will likely continue as before, the internal benchmark tests which are conducted 2-4 times per year. These tests, designed by individual school districts, will continue as before.

The heart of the school crisis is caused by this series of benchmark tests and the teaching schedule.

Consider:

(By they way, no less than John Merrow, education correspondent for the PBS NewsHour agrees with the following analysis. See his post on Opting out on his blog, takingnote.learningmatters.tv).

Organizing school districts with testing and the schedule guarantees:

A) some students will be ahead, bored, idle and not working;

B) some will be behind, tending to fall more behind, a problem which only compounds.

A follow-the-schedule method, enforced with tests causes students to fall more behind, relative to grade level, on average, the more years spent in public school. In fact some fall so far behind, and realizing that far from catching up they are falling even more behind, they drop out.

And yet, attempting to get students to keep up with the schedule is attempting to solve the wrong problem.

Why?

Moving away from the schedule requires students get some amount of autonomy. This presents a different problem, the actual challenge of education. Many students, are not _yet_ able to wisely and responsibly use the freedom required to follow their own individual plan. When autonomy is provided to students who are unready for that freedom, the result is chaos.

You see the problem. For students to have their own plan, they need autonomy, autonomy many students are not _yet_ ready for.

It seems like our two choices are guarantee chaos or guarantee idleness.

There is a 3rd way from the Latin origination of education, educere, meaning to lead out the student from within.

IF we could, and we can (we have evidence), by leading students through inner exercises in an “inner gymnasium”, little by little (it takes about a month), students begin to better hear the wise part within, develop the skill of the will, and a deep satisfaction takes hold;

THEN it becomes safe to provide the very autonomy students need to work on challenges just right for each student.

This is real education work – leading out the student from within – done by trained educators. Only students can do the knowledge work, the reading, writing and arithmetic.

Leading out students from within begins to solve the structural problem of ‘the-one’ and ‘the-many’ that is unique to eduction work.

In summary, it is the method that superintendents impose upon teachers, a scheduled teaching and benchmark tests, which is the cause of students falling behind.

A report on how superintendents organize the school district is highly called for.

All the best John,

Bob

Paul Muench 9 years ago9 years ago

Whose the most in most agree that Common Core standards are more challenging than California's previous standards? The Fordham Institute is the only organization I know of that made a systematic comparison of Common Core to state standards. In Fordham's judgement the prior California standards were judged to be on par with Common Core. In our district there's been a lot of talk that Smarter Balanced will be harder as it would have fewer … Read More

Whose the most in most agree that Common Core standards are more challenging than California’s previous standards? The Fordham Institute is the only organization I know of that made a systematic comparison of Common Core to state standards. In Fordham’s judgement the prior California standards were judged to be on par with Common Core.

In our district there’s been a lot of talk that Smarter Balanced will be harder as it would have fewer multiple choice questions and include task oriented questions. After Doug McRae’s answers on SB It seems SB may have more multiple choice questions than I’ve heard. Either way, more challenging tests don’t mean more challenging standards.

Replies

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

Interesting , Paul; however, you should make inquiries into Diane Ravitch's statements on Fordham, as she was a foundation member as I recall. Also, Fordham is known to have a pretty well defined political lens through which it does evaluations of things like state standards. If you share their lens, then their evaluations make sense. If you don't, they don't. Recall that the development and adoption of CCSS was to escape the "laundry list" model … Read More

Interesting , Paul; however, you should make inquiries into Diane Ravitch’s statements on Fordham, as she was a foundation member as I recall. Also, Fordham is known to have a pretty well defined political lens through which it does evaluations of things like state standards.

If you share their lens, then their evaluations make sense. If you don’t, they don’t.

Recall that the development and adoption of CCSS was to escape the “laundry list” model of standards that focused more on students memorizing (relatively) disconnected facts as opposed to a more critical thinking based model of pedagogy.

Paul Muench 9 years ago9 years ago

Gary, I've read both standards and both are presented as lists of items. So I'm not sure what you mean by laundry lists. Here's one standard from the Common Core: CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.7.RP.A.2.A Decide whether two quantities are in a proportional relationship, e.g., by testing for equivalent ratios in a table or graphing on a coordinate plane and observing whether the graph is a straight line through the origin. Here's one form the California stamdards: 4.0 Students solve simple linear … Read More

Gary,

I’ve read both standards and both are presented as lists of items. So I’m not sure what you mean by laundry lists. Here’s one standard from the Common Core:

CCSS.MATH.CONTENT.7.RP.A.2.A

Decide whether two quantities are in a proportional relationship, e.g., by testing for equivalent ratios in a table or graphing on a coordinate plane and observing whether the graph is a straight line through the origin.

Here’s one form the California stamdards:

4.0 Students solve simple linear equations and inequalities over the rational numbers:

4.1 Solve two-step linear equations and inequalities in one variable over the rational numbers, interpret the solution or solutions in the context from which they arose, and verify the reasonableness of the results.

4.2 Solve multistep problems involving rate, average speed, distance, and time or a direct variation.

I think these examples are representative of the standards as a whole. I don’t see anything in either of these standards that require a teacher or prevent a teacher from teaching the material critically. Can you explain further?