Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

California is just weeks away from learning whether its test of the test will pass or fail.

For nearly 12 weeks, beginning March 25, more than 3 million students in grades 3 through 8 and 11 will take the computer-based Smarter Balanced field, or practice, test aligned to the Common Core State Standards in math and English. But instead of assessing students’ skills, this year only, the exam – which was delayed a week from its previous March 18 start date – will be used to help officials evaluate the quality of the test questions to ensure that they’re valid and fair for all students, and it will assess the adequacy of computers and technology linking the state’s 10,000-plus schools to the Internet.

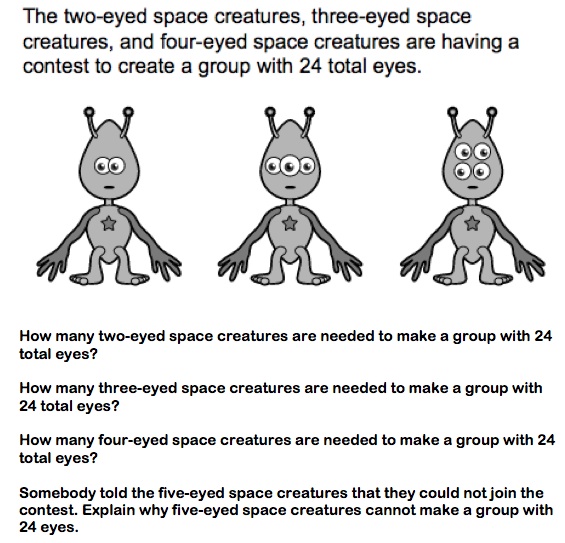

A grade 4 math practice question tests how well students understand factoring, divisibility and remainders. (Click to enlarge) Credit: Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium.

Student scores won’t matter until next spring, when the online tests officially replace the California Standards Tests and other assessments that formed the state’s Standardized Testing and Reporting program, known as STAR, for the past 15 years. Instead of the bubble-in, multiple-choice tests that have been the hallmark of standardized testing in the state, the online assessments will require students to demonstrate a deeper level of knowledge through persuasive writing, problem solving and explaining how they found their answers.

Judging by the numbers, California appears to have at least the minimum technology needed for the test. The latest figures from a survey conducted by the Department of Education show that 88 percent of school districts and 83 percent of schools are connected to the K-12 High Speed Network, a high-speed Internet connection for schools funded by the state Department of Education.

Behind the connectivity numbers, the standard of readiness is imprecise and inconsistent.

“What does ‘ready’ mean? That’s what we’re about to find out,” said David Plank, executive director of Policy Analysis for California Education, a nonpartisan, nonprofit research center. “I think we’re all flying blind on this and we’re going to find out what we’re able to do.”

(See companion piece on the skills students need for the new test.)

What is certain is that just being connected to the K-12 High Speed Network isn’t enough. Hundreds of schools don’t have sufficient computers, keyboards and headphones for all their students, or have sufficient bandwidth to run the data-heavy test that uses videos, animated graphics and interactive graphs in the questions. Some children will be bused to other schools in their district that have better computer access. Some campuses are leasing mobile computer labs. Still others are testing a few students at a time to avoid a network crash.

“People are finding ways to have their students tested,” said Deb Sigman, deputy superintendent of the California Department of Education. “We’re not hearing horror stories from folks.”

During this last mile before the field test, Sigman said the Educational Testing Service, ETS, a state contractor helping districts prepare for the field test, “has a team of people doing site visits and helping schools find creative solutions” to technological challenges.

California had the opportunity to take part in a free evaluation offered by the nonprofit EducationSuperHighway that would have identified schools without the necessary bandwidth to handle the Smarter Balanced field test, but decided against it. Completing the assessment would have taken each school a couple of minutes to log into the organization’s speed test site and run the program. Founded by entrepreneur Evan Marwell, the organization received $9 million from the Gates and Zuckerberg foundations for its initiative to connect every school in the country to high-speed Internet.

California Department of Education spokesperson Tina Jung said the department opted out because it was focused on getting schools to complete the department’s tech readiness survey, a self-reported inventory to determine if schools meet the minimum requirements for bandwidth, operating systems and available computers and other equipment.

“We were heavily promoting that, at the same time that the EducationSuperHighway came out. So we didn’t want to overburden or confuse our schools during this critical time,” Jung said.

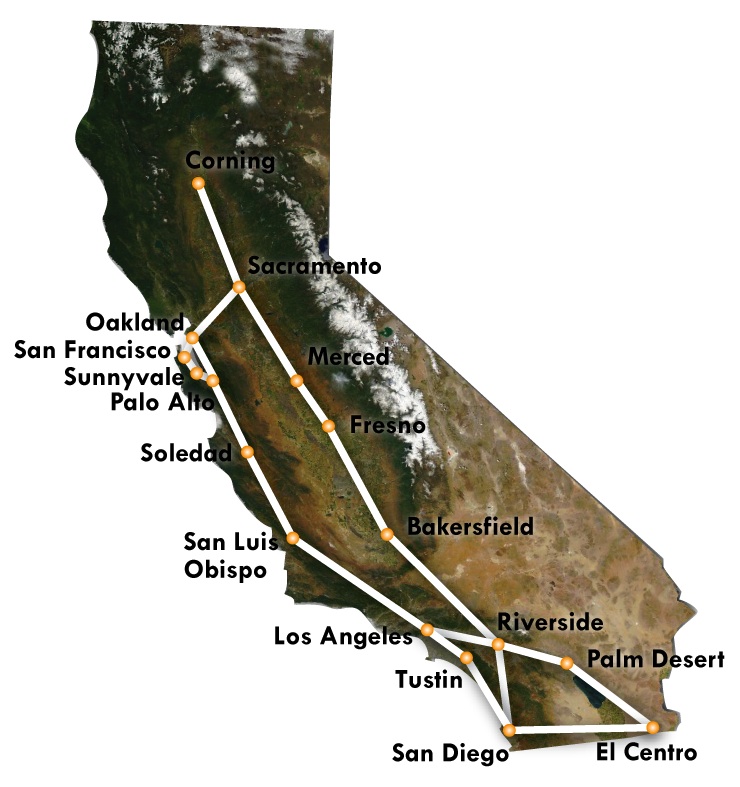

California’s K-12 high-speed network uses the 3,800-mile California Research and Education Network, an Internet just for schools, state colleges and universities and a few private colleges. Credit: The California Research and Education Network

In San Mateo County, 23 districts took the speed test and found the results helped pinpoint their connectivity needs. The County Office of Education asked the districts to participate as part of a larger project to develop models of teaching using technology. Overall, the county’s schools are in better shape than those in most of the country, although only about a third of schools have adequate bandwidth for the field test, according to the EducationSuperHighway.

As a direct consequence of the speed test, San Mateo County districts on the borderline of readiness had time to improve their technology, said Brian Simmons, director of accountability, innovation and results for the County Office of Education.

“The good thing about this fire drill is that the system has responded,” Simmons said. “I was in one district that had just gotten a bunch of Chromebooks, so I think that (the speed test) has had that impact.”

There are still a few outliers. Simmons said some 5 to 10 percent of the districts will need support during testing, such as using portable computer labs and bringing in mobile hotspots to expand bandwidth.

A number of California districts are making do with MacGyver-like resourcefulness.

Cuyama Joint Unified School District serves about 240 students in a remote farming community surrounded by mountains in Santa Barbara County. As the crow flies, it’s midway between Bakersfield, 64 miles to the east, and Santa Maria, 60 miles to the west, which is also the nearest link to the K-12 High Speed Network. As network cables lie, well, fuggedaboutit.

When testing begins, the 101 students in grades 3-8 at Cuyama Elementary School will be bused to the high school over several days to take the field test in Cuyama Valley High’s computer lab.

Death Valley Unified School District, which covers 6,000 square miles of the Mojave Desert and has skimpy cell phone service, is going to test its 20 students one at a time, said Cindy Kazanis, director of educational data management at the California Department of Education. The math and English sections are each expected to take three to four hours to complete and districts say they’ll spread that out over several days. Fortunately, at nearly 12 weeks, the window for the field test is long enough to do this.

Suburban Sacramento’s Natomas Unified School District has limited bandwidth, said Kazanis, and found that it couldn’t test classrooms next to each other without crashing the computers, so the district scheduled testing for every other classroom.

Matt Kinzie, chief technology officer for the nearly 57,000-student San Francisco Unified School District, said the district “is feeling pretty confident about the field test.” About 15 schools don’t have enough computers, so the district ordered laptops that can easily be moved from school to school during the testing period.

One potential pitfall is that San Francisco schools run at least three different operating systems: Apple, Windows and Google Chromebooks. The latter poses the biggest challenge because Chromebooks only operate in the cloud on Google’s browser.

“I’m hoping we don’t have the same experience as Obamacare,” Kinzie joked, a reference to website woes that plagued the roll-out of the health care program.

Kazanis is also advising districts with minimum bandwidth to try to keep the network as open as possible during testing by holding off on some administrative tasks.

“Keep in mind that the networks are already being utilized to a certain capacity and this takes it above and beyond that, so part of the guidance that we’ve been giving is don’t do your payroll Monday morning when getting ready to take the big test,” Kazanis said.

The state does have emergency plans for the testing period in the event that a student presses a key and his or her screen goes blank, or the network freezes and there’s no tech expert on site. ETS specialists will be on hand through a toll-free number on the California Technical Assistance website.

A common thread linking districts with technology gaps is money; more specifically, not enough of it.

San Francisco Unified has spent $836,000 this year for new computers, keyboards and headsets for testing, and has plans to buy 5,300 Apple computers next year to start standardizing the district on a single operating system.

Cuyama Joint Unified bought 28 new computers this year for the high school lab. Superintendent Roland Maier said he wants to add a lab at the elementary school and make other system upgrades, at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars.

Both districts used their portion of funds from the $1.25 billion one-time Common Core implementation grant that Gov. Jerry Brown put into the May budget revision last spring. That money, about $200 per student, could be used for technology, professional development and textbooks or other instructional materials.

“What I’m hoping more than anything is that the governor will decide to put another $1.25 or $2 billion into (implementation),” Maier said, “because we need a lot more and I know most schools do need a lot more.”

Assemblywoman Susan Bonilla, D-Concord, who advocated for the funding last year, said she’s heard that appeal from many superintendents, principals and teachers. Earlier this month, she introduced legislation seeking another one-time round of transition funds to implement Common Core State Standards. Assembly Bill 2319 doesn’t list a specific dollar amount, but in an interview, Bonilla said she’d like an additional $1.5 billion, which is what she had hoped for last year.

That will only cover half of what schools need to prepare for Common Core, contends Wes Smith, executive director of the Association of California School Administrators. ACSA is calling for two set-asides: $1.5 billion for technology and $1.25 billion for professional development, curriculum development and instructional materials.

He said superintendents told him they’re worried that without adequate preparation California will “suffer the same fate as other states” – New York in particular, which caused a backlash against Common Core by testing students before they were ready.

Smith’s fundamental concern, however, is the consequences of an unequal distribution of technology for the state’s poorest students, and not just on the field test, but also having access to the full potential of the new standards. Technology skills, from basic keyboarding to research, are embedded throughout Common Core.

“We believe at the heart of all this is opportunity. We’re at a crossroads where we can provide opportunity for all children and really invest in a real transition,” Smith said. “We’re really concerned here that we have a civil rights issue brewing that some of our wealthiest communities have access to technology and have for some time.”

Low-income students and their schools could feel that deficit next spring when the Smarter Balanced assessment is graded. During the first three years of the actual exam, schools can give a traditional paper-and-pencil version, but those students will miss out on familiarizing themselves with the online version, which will be required in 2018, and they’ll lose opportunities for personalized learning. The computerized version of the test is adaptive; it adjusts the difficulty of questions based on students’ answers. That gives teachers more information about where their students need help.

“We don’t see any world where that’s equitable,” Smith said.

State officials point out that the purpose of the field test is to get an accurate accounting of each school’s technological capabilities before the exam has consequences so there’s time to address the glitches.

“For the most part districts see this as a great opportunity,” said CDE’s Kazanis. “If something is going to fail, this is the year for that to occur. Mistakes are going to happen and we want to make them when the stakes are low.”

Contact senior reporter Kathryn Baron and follow her on Twitter @TchersPet. Sign up here for a no-cost online subscription to EdSource Today for reports from the largest education reporting team in California.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (5)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Jack Titchener 7 years ago7 years ago

Thank you for addressing the capacities of schools in providing up-to-date equipment for students. I remember my old elementary school not having the high quality computer tech, which made running online assessments difficult to operate. Thanks to your article maybe come more schools will be subsidized to buy newer computer equipment enabling kids everywhere to learn in the virtual classroom.

aprender ingles 10 years ago10 years ago

Applied arts is gaining greater popularity every day. E-learning has therefore, enabled a range of approaches towards getting

more employers to recognise the benefits of studying Internet

Marketing in a web-based environment, with functionality, course content and

interaction with staff the key to successful learning.

Now, however, they are in danger of being the norm, and insufficient

for the new breed of employer for whom paper qualifications mean more than experience.

Avi Black 10 years ago10 years ago

A key factual error at the very beginning of the second paragraph (apologies if someone has already commented): student test scores will NOT matter next spring any more than this year, as the API will not be reinstated (incorporating SBAC data) until Spring 2016. Source: EdSource itself! See http://edsource.org/2014/state-board-makes-it-official-no-api-scores-for-next-two-years/59387?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+EdsourceToday+%28EdSource+Today%29#.UznZi6hdW7w

Lennox 10 years ago10 years ago

El,

You are so right. Schools, or establishments on the whole, need to have budgeted or committed some money every year, so that every three to four years they can replace a certain percentage of their hardware. Software needs to be upgraded at every major upgrade, for example from Office 2007 to Office 2010 etc. If that does not happen the institution will be locked into a time-space warp, and end up being like Dinny the Dinosaur before too long

el 10 years ago10 years ago

We are kidding ourselves with this "one time" money. Computers aren't one time purchases - they're a permanent commitment. The typical lifespan of a laptop computer is around 3 years, and the way they are being used, I would expect each to need a new $100 battery annually on average. No one would try to run a private company of 250 computer users without a couple of full time IT staffers on site, but there's no … Read More

We are kidding ourselves with this “one time” money. Computers aren’t one time purchases – they’re a permanent commitment. The typical lifespan of a laptop computer is around 3 years, and the way they are being used, I would expect each to need a new $100 battery annually on average.

No one would try to run a private company of 250 computer users without a couple of full time IT staffers on site, but there’s no new money to hire IT staff to support kids and teachers.

I appreciate that Ms. Baron went literally off the beaten path to query some of these off-the-network districts. Frankly, there’s no excuse for the US to have any schools still lacking broadband access. It’s a need not just for testing, but also for everyday operations of the district and for getting those kids as much access to the world as possible. Those districts already are likely doing without rich libraries and local subject matter experts; the least we can do is open a line of communication to places that do have them.