While the leadership turmoil in the Los Angeles Unified School District has attracted widespread attention in recent months, the state’s largest district is far from the only one in California that is coping with superintendent turnover.

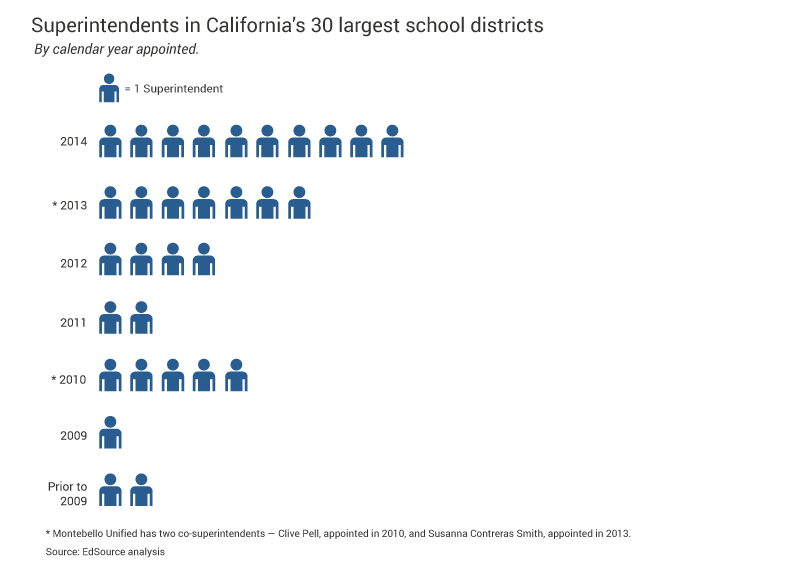

Two-thirds of the superintendents of the state’s 30 largest districts have been in their posts for three or fewer years, according to an EdSource review. Ten have been in their posts for less than a year. Only three – Long Beach Unified’s Chris Steinhauser, Fresno Unified’s Michael Hanson and Chino Valley Unified’s Wayne Joseph – have been on the job for more than five years.

The most recent appointment is former schools chief Ramon Cortines, who was named interim superintendent of L.A. Unified in October after John Deasy resigned in the wake of a series of conflicts with the elected board of education. Deasy was on the job 3½ years.

Short tenure is a prominent feature of urban districts where superintendents typically face intense pressures to raise low test scores, cope with periodic budget shortfalls that may require layoffs and school closings, as well as manage the often high-wire politics of elected school boards.

“Turnover is endemic to the position of superintendent,” said Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution in Washington D.C.

In California, the turnover comes at a time when district finances are improving but superintendents have the added charge of implementing some of the most significant reforms in decades, most notably the Common Core standards and the Local Control Funding Formula.

“In general, the job is grueling, is incredibly difficult,” said Becca Bracy Knight, executive director of the Broad Center for the Management of School Systems in Los Angeles, in a previous interview with EdSource. “It takes a personal and professional toll on people who are in it. This is a job where you have thousands of bosses, and that is very hard. Getting a governance and leadership team that works well together to serve teachers, students and families is very difficult, and rarer than it should be.”

A fall survey from the Council of the Great City Schools found that the average length of tenure for current superintendents in the nation’s largest urban school districts was 3.18 years, down from 3.64 years in its 2010 survey. It was 4.5 years for immediate past superintendents, down from 5.1 years in 2010. A 2012 study of 100 randomly selected California school districts indicated that 43 percent of superintendents stayed in their posts for three or fewer years. But 71 percent of those in districts with more than 29,000 student also left within that time frame.

“Turnover is endemic to the position of superintendent,” said Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution in Washington D.C.

Marshall Smith, the former dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Education and U.S. undersecretary of education in the Clinton administration, said that it takes far longer than the average length of tenure for superintendents to make reforms stick.

“Unless you are there for eight to nine years, you can’t expect to make big changes,” Smith said. Nor, he said, “can you expect to make changes during a fiscal crisis” – precisely the conditions that every superintendent in California experienced during the past five years.

It may be no accident that the only two California school districts that won the prestigious Broad Prize for Urban Education – Long Beach in 2003 and Garden Grove in 2004 – have been marked by unusual stability in leadership. In Long Beach, current superintendent Steinhauser, who assumed his post in 2002, succeeded Carl Cohn, who had been there for 10 years. At Garden Grove, Laura Schwalm stepped down last year after 14 years in her post – and was succeeded by Gabriela Mafi, herself a former principal and assistant superintendent in the district.

In some cases, the transition to a new superintendent can be a smooth one – when a departing superintendent left not because of conflict but because he or she is retiring or finds a job elsewhere after a relatively long tenure.

The changeover can be especially painless if the incoming superintendent is a current employee in the district. That is what occurred in the Poway Unified School District, where John Collins, a longtime administrator, replaced the highly regarded Don Phillips, who retired in 2010 after nine years on the job. In August of this year in the Kern Union High School District Byron Schaefer, who had been in the district for a quarter century, replaced Don Carter, who retired after 10 years in the post — and 38 years in the district.

But in other cases leadership changes have occurred abruptly – leaving districts scrambling to find replacements with short notice, or to come up with a temporary solution by appointing an interim superintendent.

- In April 2013, Oakland schools chief Tony Smith announced he would leave the 46,000-student district in June of that year – too soon to find a permanent replacement – and he was succeeded by interim superintendent Gary Yee. Oakland appointed a permanent replacement, Antwan Wilson, in July of this year.

- Also in April 2013, Thelma Melendez announced her resignation after just two years at the helm of the 57,000-student Santa Ana Unified School District, effective at the end of the school year. She was succeeded by former Riverside Unified Superintendent Rick Miller, who assumed his post last November – well into the school year.

- In October 2013, Sacramento City Unified Superintendent Jonathan Raymond, after 4½ years on the job, announced he would leave the district by the end of the year. He was succeeded by interim superintendent Sara Noguchi, who in turn was replaced by former Seattle Public Schools Superintendent Jose Banda in July.

These resignations were in part a fallout of the budget battles over the last five years that have resulted in bruising conflicts with teachers unions or parent and community organizations.

Both Smith and Raymond closed down schools with low enrollments as budget savings measures. School closures are arguably the most stressful transformations any school district can experience, because they inevitably trigger resistance from parents and the communities the schools serve, as well as the staff in those schools who will either lose their jobs or be forced to transfer to other schools.

In contrast, Deasy’s resignation came at a time when the district’s financial outlook had improved dramatically as a result of the state’s improving economy and the new school financing law that provides nearly additional funds to districts based on their enrollment of low-income children, foster youth and English learners.

In an interview with NPR, Deasy said a major reason he left the district was because of a clash between his advocacy on behalf of “students’ rights” vs. “adult and political agendas.” That appeared to be code for Deasy’s support of a range of reforms opposed by teachers’ unions, including the Vergara lawsuit, which seeks changes in teacher tenure and other job protection laws. At the same time, he said, “I could have developed and adjusted my style to have worked with my bosses better. Maybe my pace and way I went about it is open to critique.”

Deasy’s supporters noted that under his leadership, graduation rates and test scores had improved. But it is not clear just how much of these improvements could be attributed directly to Deasy, how much to changes that were in place when he arrived, and how much to the work of teachers and other personnel at the local level.

There has been surprisingly little research about what impact superintendent turnover has on student academic outcomes. As Jason Grissom and Stephanie Andersen noted in their paper, “Why Superintendents Turn Over,” published in 2012 in the American Educational Research Journal, “lamentably superintendent turnover lacks a well-developed research base.”

In September of this year, the Brookings Institution published one of the few quantitative studies on the subject, with the provocative title, “School Superintendents: Vital or Irrelevant?”

Co-authored by Matthew Chingos, Whitehurst and Matharein Lindquist, the study looked at superintendent turnover in Florida and North Carolina between 2000 and 2010. It found that the average tenure was between three and four years – but how long a superintendent was in a district was not correlated with the academic outcomes of its students.

In fact, said Whitehurst in an interview, “we find that which teacher students have makes the most difference, and after that what school and what district they’re in. There is little effect from what superintendent is serving in the district.”

One reason that it made little difference is that superintendents may not have been in their posts long enough to effect significant change.

“I’ve talked to some thoughtful superintendents,” Whitehurst said. “Their view is that they really don’t have control over the levers of change, they don’t have the ability to change the nature of their district’s workforce, like providing them with differential pay. They are constrained by school boards who often have advocates within the district itself, especially teachers.”

Whitehurst said superintendents “find it difficult to get things done, and frustrations build on both sides, and they leave.”

Stanford education professor emeritus Larry Cuban said part of the problem is that school boards often look for a “Superman or Wonder Woman.” While these rare superstars may succeed in one district, Cuban noted, they might not in another.

In an October post, Cuban wrote:

To lessen the inevitable disappointment that follows the appointment of a savior school chief, mayors and school boards would do well to downsize expectations, display more patience, seek leaders who believe in incremental changes toward fundamental ends, and pay far more attention to sniffing out better matches between the person and the city than betting on a super-star bearing a tin-plated reputation.

It is possible that with the easing of the Great Recession, and the infusion of funds into urban school districts as a result of the state’s reform of its school funding system that California’s crop of recently appointed superintendents will face fewer pressures than some of their predecessors. That could result in them staying longer on the job – and allow them to oversee the full implementation of the Common Core and other reforms underway in their districts.

Regardless of how long they stay, there is widespread agreement that these are exceptionally tough jobs.

“It is not magic, it is not angel dust,” said Marshall Smith, currently a visiting scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for the Advancement of Teaching. “It is just hard work.”

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.