The State Board of Education this week could revise the process that districts use to create their funding and accountability plans. At a hearing in Sacramento on Thursday, critics will argue that the proposed changes don’t go far enough.

In response to hundreds of public comments, the state board will consider explicitly requiring districts to consult with students as they write their Local Control and Accountability Plans, which lay out budget and student achievement priorities. The plans are a critical component of the community and parent participation that the state’s new school funding system mandates. The board will also review a redesign of the LCAP template and may add a requirement that makes it clear that extra money for “high-needs” students must be used “principally” to benefit them. Civil rights groups lobbied heavily for the new wording.

“We all know so much more than we did in March and [are now] seeing issues that we didn’t see coming,” said David Sapp, education director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

While responsive to many of the public’s suggestions, the state board’s proposals fall short of satisfying a coalition of civil rights and children’s advocacy groups. They had sought more specific language in the LCAP to track how money is spent on high-needs students – low-income pupils, English learners and foster youth. They also want to be able to compare expenditures across districts through uniform accounting codes. And they asked the board to give explicit directions to county offices of education, which are charged with monitoring the plans, so they know what constitutes an unsatisfactory LCAP.

Brooks Allen, the state board’s deputy policy director and assistant legal counsel, said that board staff incorporated at least partially the “vast majority” of suggestions. “Most folks were not suggesting radical overhauls” of the regulations, he said.

David Sapp, the education director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, agreed that staff did include some key recommendations, though he and others will push for more at the July 10 board meeting. What the revisions don’t respond to, he said, is “experience” – what he and others have observed over the past few months. The period for public comments ended in March, when only a few districts had begun to write their first LCAPs, which school boards were required to approve by the end of June.

“We all know so much more than we did in March and [are now] seeing issues that we didn’t see coming,” Sapp said.

Out of misunderstanding or haste, some districts didn’t incorporate basic information or lay out all required levels of spending, sometimes on the bad advice of county offices of education, he said. He said a coalition of civil rights and parents’ groups will propose changes during a 15-day comment period after the meeting.

The new Local Control Funding Formula governs most district funding and allocates supplemental dollars to districts for their high-needs students. The Legislature mandated that each district’s funding plan address eight academic and school priorities and document progress through the use of common metrics. The priorities fall into three categories: student achievement (standardized test scores and college readiness measures), engagement (student suspension rates and parent involvement) and conditions of learning (access to materials, courses and qualified teachers, adequate facilities, and implementation of Common Core state standards).

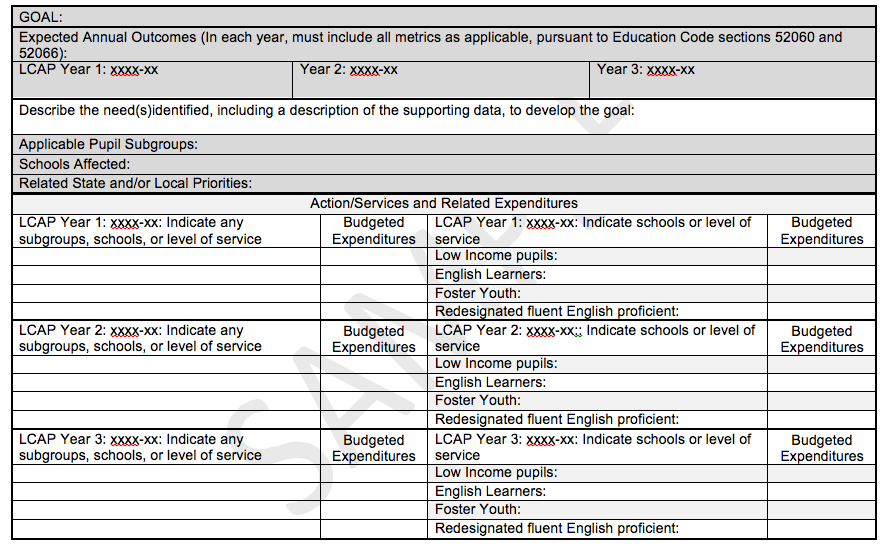

The current template puts goals for student achievement in one section of the LCAP and actions and expenditures to achieve them in another section, making the LCAP difficult to follow.

In writing their LCAPs, districts must document how they involved the public – including parents and teachers – in creating goals and action plans for students, and high-needs students in particular. The funding regulations permit using additional dollars targeted for high-needs students for schoolwide and districtwide purposes benefiting all students. However, the programs must be the most effective choice for improving or expanding services for high-needs students.

Districts are supposed to explain how spending will help achieve all eight priorities, but some districts have skipped priorities or included only the new money under the formula they received this year, not the base funding they’ve also been getting.

The new format should make the process easier and the requirements more logical, Allen said. Under the current template, the goals and objectives are in one section of the plan, and the corresponding list of expenditures and actions are in another. That requires flipping pages back and forth in a complex document often dozens of pages long, with no clear connections.

The new template combines them in one place (Section 2), to make it clear which goal applies to which priority. It elaborates on which metrics, like suspension and graduation rates, must be used as a baseline measure, and ties spending and programs to goals for each of the three years covered by the LCAP.

“We thought we had clear instructions” in the current template, Allen said, “but we heard a lot of questions and confusion.”

The proposed template also would add a lengthy section for annual updates.

Sapp agreed that the new format will be an improvement. Some superintendents had already decided how to spend money and then worked backward to come up with a rationale instead of starting with an assessment of needs. “This format will make it harder not to honor the intent of the LCAP and start with goals, not programs,” he said.

Other proposed fixes

More student participation: State law requires districts to consult with several school groups, including students, on developing the LCAP, but student groups have complained to the state board that they’ve been ignored.

Credit: John Fensterwald/EdSource Today

Taryn Ishida

The proposed regulations elaborate on the consultation process with examples of what it might entail: surveys, forums, meetings with student governments or other groups representing pupils.

Taryn Ishida, executive director of the nonprofit student advocacy group Californians for Justice, said she’s appreciative that the staff recognized the need for a formal role for students, but the proposal doesn’t go far enough. More than 150 students will head to Sacramento this week to reinforce that point. Groups in the Student Voice Coalition asked that regulations require a student advisory committee, just as they mandate a parent advisory committee, though Allen said that would require a change in state law. And Ishida would like the board to require districts to solicit views of low-income students. Sapp called this omission in the current regulations a “glaring oversight.”

More parent participation: The proposed regulations would restate what the law requires: Parent advisory committees must be made up primarily of parents. Some districts have ignored this requirement, relying on district-level committees made up of teachers, administrators and parents.

Spending supplemental dollars: Proposed regulations state that supplemental dollars for high-needs students must be spent in ways that not only are “effective in meeting the district’s goals” for those students but also “principally directed” toward them. Advocates for low-income children, such as Children Now, the Education Trust-West and EdVoice, and civil rights groups, including the ACLU and Public Advocates, pushed hard for what Sapp called a “modest” change in wording. He said it would force districts to further explain the rationale for school-wide or district-wide uses of money for targeted students. Under the proposed wording, districts might not be able to justify, say, money spent on laptops for all students, even though high-needs students also would benefit.

Not taking no for an answer

At this week’s meeting, a coalition of groups is expected to press for two changes to the LCAP that the state board staff rejected: more direction to the county offices of education and more details on how districts spend dollars they receive for high-needs students.

Civil rights groups want the state board to require county superintendents to hold a hearing on each district’s LCAP. Allen said that the state board lacks the authority to impose this. The groups also asked that the regulations list basic elements of an LCAP that must be satisfied before a county superintendent can sign off on it, such as including metrics required by state law and setting goals for all academic priorities.

Because regulations don’t require that each expenditure be broken out by funding source in the LCAP, Sapp said it has not been possible to determine in most districts’ LCAPs how much money generated by high-needs students was actually spent on them.

That would not change under the staff proposal. Allen said that the state board’s position is that services must be expanded or improved for high-needs students in proportion to the extra dollars that the districts receive for them – but every dollar doesn’t have to be distinguished. “Shifting the focus to how each dollar is spent would steer the discussion away from providing services and measuring how students benefited from them,” Allen said.

Sapp dismissed that argument as “a bogeyman” and said the issue is transparency.

The state board could pass permanent regulations as drafted at its September meeting. But if the board agrees to further changes – Allen said it’s fair to predict it would – then there will be another hearing in September, with approval in November. The changes would apply to 2015-16, the second year of the LCAP that districts have adopted.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.