The pension reforms passed in June, paring back the benefits for new teachers and administrators, will knock off $189 million per year from the additional payments taxpayers must make to keep the California State Teachers’ Retirement System solvent over the next 30 years.

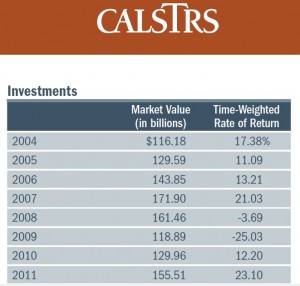

The market value of CalSTRS’ assets remains below the high in 2007. Retirement benefits for members assume a rate of return on CalSTRS’ investments of 7.5 percent annually. Because the defined benefit plan has fallen behind, without growth from compounded interest, the unfunded liability – required to keep the system solvent for the next 30 years – is now $65 billion. (Click to enlarge).

That’s the good news. The bad news is that this represents only about 6 percent of the extra $3.25 billion annually that CalSTRS actuaries are saying is needed to erase the system’s current $65 billion unfunded liability. That liability is the debt that taxpayers owe to future pensioners to compensate for shortfalls in CalSTRS’ income on investments following the Wall Street implosion in 2008. CalSTRS is still recovering from that with $152 billion in assets in July, still $20 billion below a high of $172 billion in 2007.

The Legislature hasn’t yet started paying down that liability, and it isn’t expected to until 2016 at the earliest, given the precarious state of the budget. But when it does start making a dent in the $65 billion, it will be diverting money that otherwise could go to restore funding for K-12 and community college programs.

Legislators had only a crude estimate of the financial impact of the pension reforms they passed in the final day of the session last month. The deal that legislative leaders and Gov. Jerry Brown cut didn’t leave enough time for the state’s two largest pension system – CalSTRS and CalPERS, the California Public Employee Retirement System – to do the math in time; they barely knew what was in it.

CalSTRS completed its analysis last week. It showed that the changes, in lowered benefits and higher employee contributions, will ease the pressure on the system. But it will take decades for the full impact to take effect, because the reforms will apply only to employees hired after Jan. 1, 2013. Courts have ruled that pension benefits for public employees are a vested right that can’t be undone unless employees are given something of comparable value in return, like a raise. Legislative leaders and Brown didn’t challenge that assumption in coming up with a pension deal.

Through concerted effort and rising values on Wall Street, CalSTRS’ defined benefit program became more than fully funded by 2000. A combination of new benefits followed by a plunge in investment values in 2007-08 has left it only about 70 percent funded; anything below 80 percent is a serious problem. Source: 2011 Actuarial Evaluation by the firm Milliman for CalSTRS. (Click to enlarge)

The CalSTRS analysis concluded that CalSTRS will save $22.7 billion over the next 30 years (about $12 billion if adjusted for inflation) through paying out lower benefits, though most of the savings will years from now when new employees retire.

Most of that will be achieved by raising the retirement age by two years for the same level of benefits. CalSTRS’ 430,000 active members are currently retiring on average at age 62, with 25 years of experience, for which they’re entitled to receive a benefit equal to 56 percent of their highest-year salary, about $4,000 a month on average. Future employees who retire at the same age will get 6 percentage points less: 50 percent of the average salary.

The reforms also restrict double-dipping (turning around and returning to work as a teacher or principal after retiring), and they ban pension spiking (getting a big raise in the final year of work to build up a big pension). Pensions will be determined on the average of three consecutive years of the highest pay, not the final year. And there will be an inflation-adjusted maximum income – $136,440 in 2013 – on which pensions will be based; those who earn more than that – superintendents, some administrators, and principals in a few districts – won’t get a higher pension. CalSTRS says that provision will affect only 3,400 employees, less than 1 percent of active members.

Teachers and administrators, their school districts, and the state (through the General Fund) pay into CalSTRS. The combined contribution rate is currently 18.51 percent of each employee’s pay, with the employee contributing 8 percent, the district paying 8.25 percent, and the state paying 2.26 percent. The reduced payout in benefits will eventually reduce the “normal” costs to 15.9 percent of payroll, with the savings going to the state and districts (how the savings will be split between the two isn’t clear under the new law). Employees will continue to contribute 8 percent of their pay into CalSTRS.

Last April, actuaries estimated that paying off CalSTRS’ $65 billion in unfunded liability would require raising the level of contribution an additional 12.9 percentage points, to nearly a third of an employee’s pay. That would require $3.25 billion more from the General Fund for CalSTRS alone. As a result of the passage of AB 430, the pension reform bill, the reduced benefits will offset three-quarters of 1 percentage point of the increase: $188.5 million less from taxpayers.

Cold comfort, perhaps, but still a savings.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.