Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

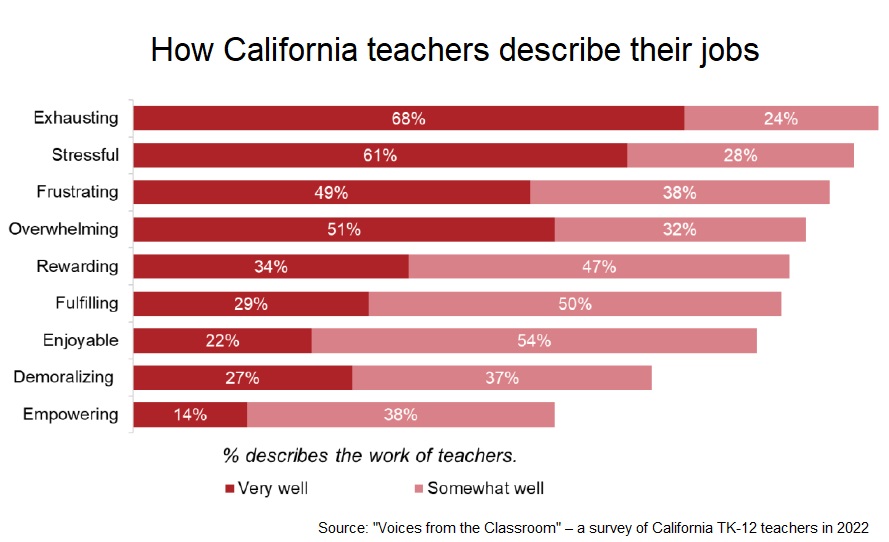

A large-scale survey this past summer of California teachers confirms what has emerged as a byproduct of two-plus years of a pandemic: Large numbers of teachers characterize their work as “stressful” and “exhausting.” And nearly twice as many teachers than in the past say that job conditions have changed for the worse.

The results of the survey of 4,632 teachers, commissioned by the California Teachers Association and UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools, was released on Tuesday. Hart Research Associates administered the survey; all the teachers are CTA members.

The survey points to multiple reasons for unhappiness, and those teachers who are considering leaving the profession cited burnout from stress (57%) and political attacks on teachers (40%), followed by a heavy workload compounded by staff shortages. A low salary, a lack of respect from parents and a lack of a work-life balance also were high on the list.

The survey found that 1 in 5 teachers say they will likely leave the profession in the next three years, including 1 in 7 who say they will definitely leave. An additional 22% say there is a 50-50 chance they will leave.

However, national data of recent teacher resignations call into question what the survey called California’s “crisis of retention.” Research and a review of surveys by Education Week concluded that the rate of teacher attrition did rise in 2021-22, but only by a few percentage points, to 7% nationally and to 10% in large urban and low-income districts.

Dan Goldhaber, vice president at the American Institutes of Research, whose study of teacher turnover in Washington state also found a slight uptick in attrition in 2021-22, said “data definitely do not support the idea that anywhere near the number of teachers who suggest they may leave actually leave.” But he added, in his Washington state analysis, “That does not mean we should be unconcerned; we should take reports of teacher burnout and dissatisfaction seriously, even if they do not lead to attrition.”

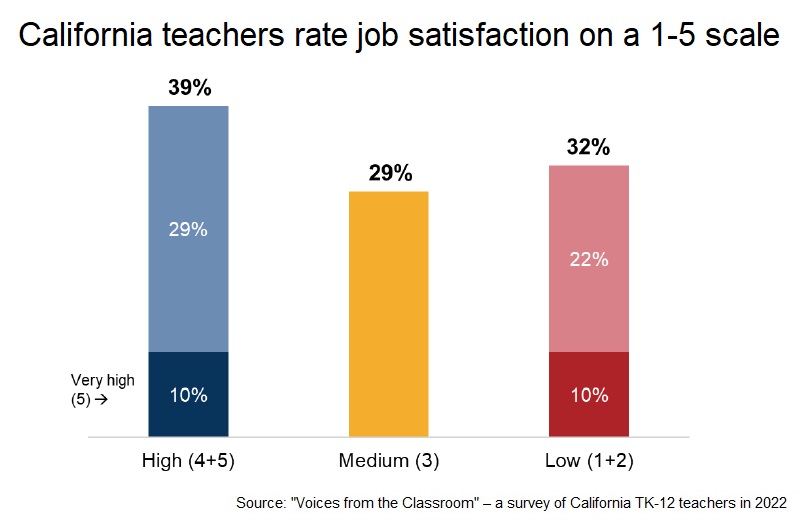

The California survey paints a nuanced portrait: While many teachers think about exiting teaching, most said they continue to like it; more than two-thirds said that they are very satisfied (39%) or moderately satisfied (29%) with their positions. That leaves 32% with low satisfaction. Older and high school teachers were more likely than younger and elementary school teachers to say they are highly satisfied. Slightly more Black and Asian American teachers indicated they will likely leave the profession than white and Latino teachers.

“There are teachers who feel satisfied with their jobs and pay structure, but it’s incumbent upon us to address why 30% say they’re not,” said Kai Monet Mathews, research director of UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools. “The changes brought about by the pandemic will have a lasting impact. Teachers are more overwhelmed than before. We should be proactive — hear the voices of teachers and listen to their concerns.”

Teachers said the primary motivation for entering and staying in the profession is to help students and make a positive difference in their lives. Schedules with summers off, job security and good pension and health benefits were secondary reasons.

But teaching has proven to have positives and negatives. Asked what they like most about their current position, current teachers cited connecting with their students (42%) and helping their students grow and develop (43%).

Yet when asked what they like least about their position, teachers pointed to student apathy, discipline and behavioral problems (32%). In two-dozen in-depth interviews, teachers said inadequate training in classroom management and a lack of support from administrators and parents compounded the behavior problems. Teachers who said they planned to leave the profession cited strengthening discipline for disruptive behaviors and raising pay as two top ways to retain teachers.

The National Education Association projected that the average teacher in California would earn $87,275 in 2020-21, the third-highest salary among teachers in the nation. Three-quarters of the teachers surveyed reported annual household incomes of more than $100,000, with 36% more than $150,000. But California is also one of the least affordable states, exacerbated by escalating housing costs in the Bay Area and Southern California.

Most of the teachers surveyed said they are experiencing financial stress: 80% said it is difficult to find affordable housing near where they teach; 75% said it was difficult to save for long-term goals, to keep up with basic expenses (68%), to save for retirement (68%), and to live comfortably and maintain the lifestyle they want (64%).

Asked for four changes to improve retention, teachers cited better pay as the top priority, followed by smaller class sizes, a more manageable workload and more support services for students.

Two dozen aspiring teachers also cited the financial burden of tuition and qualifying tests. They expressed positive views of teacher residencies, internships and clinical practice but not the cost.

“I was and am willing to do whatever it takes to be a teacher. However, the cost of tuition, compared to how much teachers make, is very sad. The cost of student-teaching was 10 grand and has been a huge challenge for me,” said one interviewee, a 23-year-old woman.

Fulfilling 600 hours of practice in a classroom to become a full-time teacher in California requires taking a semester off, Mathews said. Access to becoming a teacher is limited if you don’t have a partner or a family to support you during that time. Most affected are low-income, aspiring teachers of color, she said.

“It’s time to have a broad, creative conversation about compensation with the community,” Mathews said, and consider benefits that aren’t necessarily in the form of a monthly paycheck, like providing housing stipends, covering student loans, universal paid teacher residencies — “a GI bill for teachers,” Mathews said. “Teachers need to be seen as part of the social fabric, compensated and taken care of.”

The success of retaining and recruiting teachers in an increasingly diverse state will depend on creating school environments that support diversity. The survey indicates teachers see a need for significant improvement, although how much depends on subtle differences in perception.

More than 80% of teachers said they feel comfortable being their “authentic” selves at their schools and that their schools support different cultures; 77% said they felt a sense of belonging in school. But they were divided over whether they “strongly” or “somewhat” hold these views. Nearly two-thirds of teachers said their school leadership demonstrates a genuine commitment to cultivate diversity. But only 32% said they strongly believe that their leaders are fully committed.

The report says there are significant differences between whether white teachers and teachers of color strongly feel a sense of belonging at their school. But the data shows identical proportions — 41% — of white and Latino teachers feel that way. The data also shows, however, that Black and Asian teachers feel much less comfortable being themselves in school. A key difference, former teachers of color said, was working at a school where some or all of the population was from a similar background as their own.

Only 38% of Black teachers reported never experiencing discrimination in their current positions; 31% reported experiencing it a few times; 19% said occasionally, and 12% —1 in 8 Black teachers — said it happened very often.

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

Comments (8)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Jim 2 years ago2 years ago

Is the data available by district? I strongly suspect districts like Manhattan Beach that have high parent involvement and students that finish homework have much higher job satisfaction rates. My wife taught at a title 1 school and will never return. Students were disruptive, administration apathetic, and parents unresponsive or defensive. It was a terrible way to spend a life.

Millie O'Donnell 2 years ago2 years ago

Teaching is a 9 month job that pays better than the median worker’s wage in the US.

What relationship does this publication have with the CTA and the other teacher’s union?

Replies

John Fensterwald 2 years ago2 years ago

Millie, a more appropriate comparison is with other workers with a college education. Teachers nationwide earned 23.5% less in 2021, according to the Education Policy Institute, which has been tracking the differential for two decades. When benefits and pensions are included, the difference shrinks to 14.2% in total compensation. California does pay well above the national average, but is also one of the most expensive states to live in. Our relationship with the California Teachers … Read More

Millie, a more appropriate comparison is with other workers with a college education. Teachers nationwide earned 23.5% less in 2021, according to the Education Policy Institute, which has been tracking the differential for two decades. When benefits and pensions are included, the difference shrinks to 14.2% in total compensation. California does pay well above the national average, but is also one of the most expensive states to live in.

Our relationship with the California Teachers Association and the California Federation of Teachers is the same as with other school groups – school administrators, school boards and advocacy groups. We maintain our independence and strive for fairness and objectivity.

Jay 2 years ago2 years ago

Teaching is hardly a nine month job. The most effective teachers work without pay to always improve their lessons during the school year, weekends, and on breaks. Just because students are not in class does not mean the "side job" of a teacher is not taking place, which is curriculum development. Teachers need to be valued like other members of professional society and, yes, this starts with increased pay. The money has been provided by the … Read More

Teaching is hardly a nine month job. The most effective teachers work without pay to always improve their lessons during the school year, weekends, and on breaks. Just because students are not in class does not mean the “side job” of a teacher is not taking place, which is curriculum development.

Teachers need to be valued like other members of professional society and, yes, this starts with increased pay. The money has been provided by the legislature, but it never reaches classrooms; otherwise, you would hear of 12.5% wage increases in 2022 equal to the same 12.5% increase in funding to schools by the government (LCAP, LCFF).

Todd Maddison 2 years ago2 years ago

"The most effective teachers work without pay to always improve their lessons during the school year, weekends, and on breaks." Not true. Teaching is a salaried job, not an hourly job. Like all salaried workers, teachers are paid to get the job done, not based on a time clock. Median total compensation of a CA teacher in 2020 was $119,422. Contracted hours in most districts are about 5-600 hours less than … Read More

“The most effective teachers work without pay to always improve their lessons during the school year, weekends, and on breaks.”

Not true. Teaching is a salaried job, not an hourly job. Like all salaried workers, teachers are paid to get the job done, not based on a time clock.

Median total compensation of a CA teacher in 2020 was $119,422. Contracted hours in most districts are about 5-600 hours less than private workers consider “full time”.

Teachers are most certainly paid for their work, there is no question about that.

“Teachers need to be valued like other members of professional society and, yes, this starts with increased pay.”

In 2020 the median private employee with educational attainment comparable to a CA teacher (per US Census Bureau and CDE numbers) made about $11,000 less than teachers. If one counts the benefit advantage (contributions to retirement that private employees don’t get) that increases to about $26,000.

Is making $26K/year more than they would make using the same education in private industry for a job that requires several hundred hours less work than private employees not “being paid fairly for their work”?

If that’s not, what do you suggest is?

Since 2012 teacher pay in most districts has gone up at rates multiple times that of inflation. Overall state funding per student is up almost 3x inflation.

Neither has resulted in any measurable improvement in education.

Given actual facts and data from a decade long experiment show that “giving the same people more money” does nothing, why would anyone think that is a viable solution now?

Sue Sheridan 2 years ago2 years ago

I am just glad I am retired. Husband said, ” Do you want to be married to me or that classroom? ” I taught 28 +yrs. The last 18 in Sp. Ed. Also building rep. and on State Council. Retired N E and CTA member.

Todd Maddison 2 years ago2 years ago

The survey presents interesting information on the state of teacher job satisfaction right now, but without any historical context or comparative data is somewhat useless. Has this survey been done before, and if so what were the result then? Are comparable surveys done among non-teachers? The article opens with “And nearly twice as many teachers than in the past say that job conditions have changed for the worse” but provides no data from … Read More

The survey presents interesting information on the state of teacher job satisfaction right now, but without any historical context or comparative data is somewhat useless. Has this survey been done before, and if so what were the result then? Are comparable surveys done among non-teachers?

The article opens with “And nearly twice as many teachers than in the past say that job conditions have changed for the worse” but provides no data from those past surveys. What do those surveys say about the other measures here? Are all measures “worse”, or just this one?

And how does this compare with other non-teaching jobs? 68% of teachers describe their jobs as “exhausting”, but how does thot compare to the general population? What if 70% of everyone describes their job that way, meaning teaching is less exhausting then everyone else’s jobs? We don’t know that.

We once again see the canard of “low pay” without use of real data. “The National Education Association projected that the average teacher in California would earn $87,275 in 2020-21”, however we don’t need to project that number. We have real data, at least for one year prior (2020.)

The Transparent California database has records on over 250,000 teachers for 2020. Data that comes directly from the actual pay records of school districts, obtained through legal public records requests. That data says the median total compensation of a teacher in 2020 in our state was $119,422. That’s not a projection, that’s just math done using actual data.

Total compensation is, of course, not pay. But a teacher’s compensation includes about 17% more in contributions to retirement than private employees receive. That 17% is worth $15,000/year. If it were invested in a private 401k it would likely be worth over $2 million at retirement.

Is that not worthwhile? If you think not, suggest you ask a private employee nearing retirement how they would feel about having another $2M in their account. If we include that as part of a “comparable pay” number, a teacher in CA makes about $106,000/year. Not “riches” in some parts of CA, but certainly not “low pay” by any means.

Everyone has worked with people who repeatedly tell you how unhappy they are in their job (and with their pay) and how “someday” they’re going to just walk out the door. Most of us have likely worked with people who say that year after year without leaving. To some degree that is simply human nature – “work” is “work” because sometimes it’s not what we’d really like to be doing.

As the article points out, that’s not actually happening in teaching. At least not to any significant degree. Which doesn’t mean teachers are not less happy with their job than they have been before, but does mean they aren’t so unhappy they’re leaving.

And of course how much of the issues that are making teachers unhappy are their own doing – or, at least, their union’s doing. Parents are unhappy because the teacher’s union locked their kids out of school, which resulted in well documented increases in mental health issues and well documented declines in academic performance (which we are about to see reported by the state, finally…)

Where were teachers when parents were protesting this? Very rarely were they on the front lines, and we heard almost nothing about them lobbying their union for a change in direction.

Given the teachers union did such damage to our kids, can anyone blame parents for being unhappy with them? Who wouldn’t?

Dayle Ross 2 years ago2 years ago

I retired in 2020. I probably would have stayed longer, but I could no longer tolerate the bullying from the principal, her favorites, and other staff members. Loved being with the kids, & teaching the kids, but when others are telling parents “stories” about me, it makes it very uncomfortable. Ironically, the district mandates watching videos about bullying, but would never act when it was principal on teacher. The Union tried … Read More

I retired in 2020. I probably would have stayed longer, but I could no longer tolerate the bullying from the principal, her favorites, and other staff members. Loved being with the kids, & teaching the kids, but when others are telling parents “stories” about me, it makes it very uncomfortable. Ironically, the district mandates watching videos about bullying, but would never act when it was principal on teacher. The Union tried to help, but principal was “drinking” buddies with Superintendent!