Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

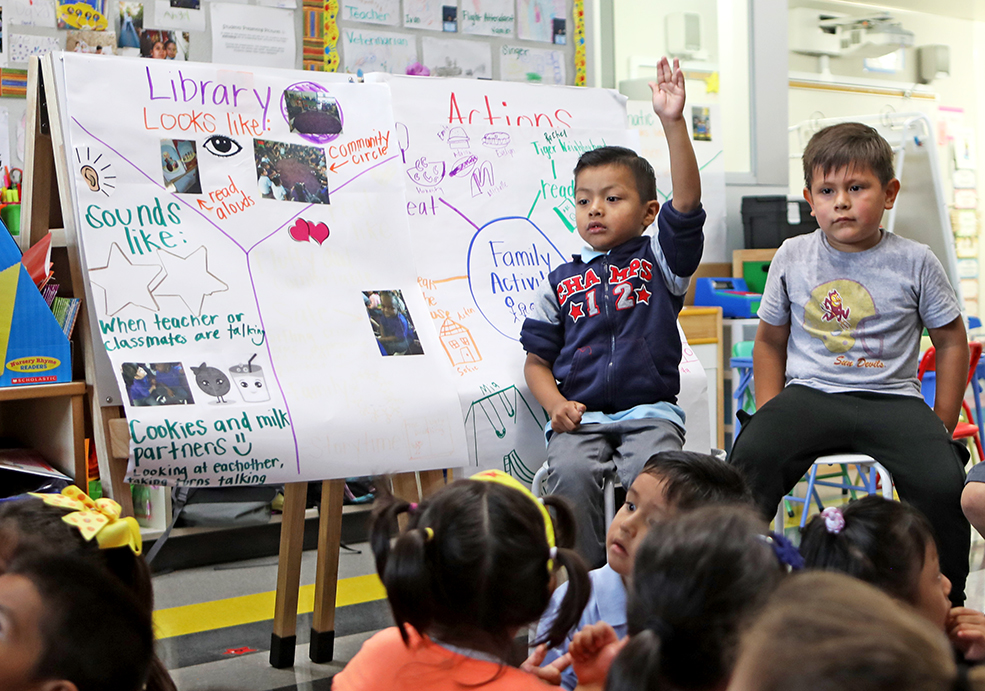

A state guide for teaching English learners is sparking innovation in school districts in Los Angeles County: classes that help students learn English and prepare students for college at the same time, parents telling stories and leading art projects in their home language in the classroom, and even journalism clubs where English learners write their own newsletter.

The English Learner Roadmap was approved in 2017 by the California State Board of Education to help school districts and education agencies better support the nearly 1.2 million English learners who attend public schools in California.

A new report from the Los Angeles County Office of Education details how nine districts and charter schools in the county have begun to implement the English Learner Roadmap. The report is based on interviews with principals, assistant superintendents and other district leaders in Centinela Valley Union High School District, Compton Unified, Downtown Value Charter School, El Rancho Unified, Green Dot Public Schools, Los Angeles Unified, Monrovia Unified, Rowland Unified and one district that chose to remain anonymous.

The county office learned that districts and charter schools have found it challenging to understand and begin to implement the road map, but that it has also both reaffirmed some existing practices for districts and paved the way for innovative changes in how they serve English learners.

Many of the districts consulted have changed some of their English language development classes to make them more engaging and, at the high school level, made them meet A-G requirements, so that students who are learning English are not shut out from opportunities to take electives and courses that prepare them for college.

For example, Green Dot Public Schools, a network of charter schools in Los Angeles, is offering African American/Latinx Literature for English learners. El Rancho Unified is also offering AP Spanish and AP Spanish Literature to new students who have recently arrived from other countries.

Compton Unified offers journalism clubs for English learners in fourth through eighth grade who have struggled with literacy. Students write a newsletter together.

“I think it’s about making it fun and empowering for children and exposing them to opportunities where they do not feel stigmatized,” said Debra Duardo, superintendent of schools for Los Angeles County.

Another program that stood out to Duardo is in Rowland Unified, where English learners are helping write curricula for their teachers.

“It was just so empowering. I have a background in social work, and for me, it’s always about how can we lift children up, how can we empower our community, how can we celebrate their contributions,” Duardo said.

District leaders said the road map has helped them differentiate between different groups of English learners and tailor classes to their needs. For example, students who recently arrived in this country have different needs from those who have been enrolled in U.S. schools for six years or more.

The road map has also inspired some districts, such as Rowland Unified, to expand their dual-language programs.

A challenge that many districts identified is overcoming the stigma that many parents and teachers associate with speaking a language other than English, especially if they were discouraged from speaking another language when they were in school. Several districts are actively encouraging parents to maintain their home language so that their children can become bilingual, and working to show parents that they see home languages as assets. Downtown Value Charter School is inviting parents to tell stories and lead art projects in their native language. Many schools are holding parent workshops about the English Learner Roadmap so that parents can understand the concepts as well.

Still, the Los Angeles County Office of Education found many obstacles that make it hard for districts to fully implement the road map. One challenge is just its sheer size and detail.

“The road map itself is so visionary, big and overwhelming. It’s hard for people to envision it in action,” said Margarita Gonzalez-Amador in the report. González-Amador is project administrator for EL RISE, one of two groups that received grants from the California Department of Education to help educate districts about the road map.

The pandemic also created a huge obstacle for districts, diverting energy and time toward shifting to online learning and conducting English language proficiency tests online. Most districts said they are worried about how to help students who are struggling after a year of online learning.

“We need to think about long-term planning, beyond recovering from this pandemic. We need to ensure that those resources are in place for the long haul,” Duardo said.

The most significant challenge found by the report is that teachers need more training about how to integrate English language development into every class and how to teach English learners to read, especially at the middle school level.

The report recommends more professional development for teachers about how to serve English learners, and that districts should hire more staff who speak the same languages or are from the same ethnic backgrounds as English learners. According to the report, the California Department of Education should integrate the road map more deeply into other efforts for all students and uplift good examples of how districts are implementing the road map that other districts can replicate.

In addition, it recommends that county offices of education create online dashboards monitoring the academic progress of different groups of English learners, assign a staff member to each district or charter school to help with implementation, and request more specific explanations in Local Contral Accountability Plans about how districts plan to serve English learners better.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments (3)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Les T. 2 years ago2 years ago

A comment on the 2 comments. In public education we have this, “we’re great but need to get better” correctness that has the effect of dulling the demand for change. I don’t really understand it, but it is so nice to see that the fire still burns out there!

Jim 2 years ago2 years ago

“LA schools make headway with English learners” Really? Then why does the article cite nothing but anecdotes from self-interested parties?

Zeev Wurman 2 years ago2 years ago

"LA Schools make headway with English learners" chirps the title of this piece, full of optimism. Headway? Sure. In he wrong direction, perhaps? The piece is silent about that. Essentially it seems this a a road back to the disastrous and discredited "bilingual education" of the 1980s and 1990s that was repealed by proposition 227 in 1998, and foolishly restored in 2016 by proposition 58. Do we see in this article any hard evidence that this … Read More

“LA Schools make headway with English learners” chirps the title of this piece, full of optimism. Headway? Sure. In he wrong direction, perhaps? The piece is silent about that.

Essentially it seems this a a road back to the disastrous and discredited “bilingual education” of the 1980s and 1990s that was repealed by proposition 227 in 1998, and foolishly restored in 2016 by proposition 58.

Do we see in this article any hard evidence that this is actually improving children ‘s language acquisition? Naah, no such thing is deemed necessary. Instead we are treated to chirpy quotes by administrators such as “it’s about making it fun and empowering for children and exposing them to opportunities where they do not feel stigmatized.”

But this excerpt is revealing: “District leaders said the road map has helped them differentiate between different groups of English learners and tailor classes to their needs. For example, students who recently arrived in this country have different needs from those who have been enrolled in U.S. schools for six years or more.”

In other words, we now expect English Language Learners to remain n this status for five years. I doubt there is anything more wrong-headed and cruel than sentence non-English speakers to five years of linguistic ghetto in California schools, yet that is what out “new and improved” system expects.

For comparison, I emigrated to Israel to a second grade and easily half of my class were newcomers like me. Within a year most of us spoke and read fluent Hebrew and within two years you’d be hard pressed to identify natives from immigrants by their language skills.