Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Alice Campbell is only 7 years old but already has definite opinions about books. Her favorite is “Cat in the Hat,” followed closely by “One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish” and “Fox in Socks.”

“I love reading and I’m very, very good at it,” she said during a recent break at her first grade classroom at Lockeford Elementary, amid the vineyards, almond orchards and horse ranches northeast of Lodi in the Central Valley. “It’s super-duper fun.”

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

Alice Campbell finds reading “super-duper fun.”

Alice is not an outlier. Thanks to federal Covid relief funds, she and many of her classmates are now participating in a reading program first introduced in the district in 2014.

Many of the students are reading at grade level or beyond, even after a year of distance learning that saw children throughout California fall behind academically.

Every day, Alice and her classmates learn new words, practice letter sounds and work their way through simple books.

With $131 million in federal and state Covid relief funds, Lodi Unified chose to prioritize literacy and social-emotional learning in its plan to help students recover from the pandemic.

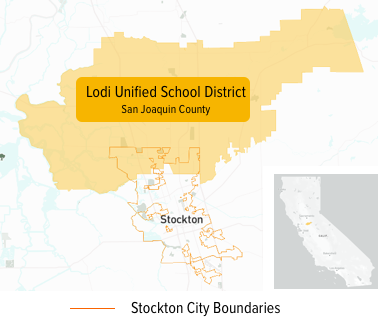

So far, the district has spent nearly $500,000 on teacher training and materials for a reading program called Systemic Instruction in Phenome Awareness, Phonics and Sight Words, or SIPPS, which initially was only used at two of the district’s 32 elementary schools in Lodi, northern Stockton and surrounding areas.

SIPPS had shown great success in boosting literacy test scores at those two schools. At Leroy Nichols Elementary, the percentage of third graders who met or exceeded the state standard doubled from 2014, when SIPPS was introduced, until 2019.

At Borchardt Elementary, the percentage jumped dramatically, as well. In 2019, just before schools closed due to Covid, nearly 53% of district third graders met or exceeded the state standard for English language arts, 4 points higher than the state average.

Covid funds allowed Lodi to expand the program to every elementary school. It was an easy choice, said Susan Petersen, the district’s director of elementary education.

“In order to have a healthy, thriving community, our schools’ No. 1 priority is to send every child into the world knowing how to read. If you can read, then you can access everything else out there,” Petersen said. “It’s amazing what’s happened. Its positive impact has spread like wildflowers.”

Lockeford Elementary, a 500-student K-8 school, spent $40,000 in Covid funds for SIPPS books, flashcards and other materials, as well as training for teachers. It’s now used in all kindergarten through third grade classrooms as well as after-school programs.

Principal Michael Rogers said the impact was almost immediate.

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

Lockeford Elementary principal Michael Rogers helps a first grade student with sight words on the computer.

Reading scores soared – in the beginning of the year, only 18% of first graders were proficient or advanced in reading, but by midyear, 44% were. Among kindergartners, the percentage of students who were proficient or advanced nearly doubled.

But the benefits stretched far beyond academic, he said. Campus climate improved, and students started to do well in other subjects, as well.

“We just saw a boost in confidence across the board,” Rogers said. “How do you know when a student is successful? When they’re happy. You can just see the stress lifting from their shoulders.”

The pandemic was tough for many students in the tight-knit community of Lockeford, where many are from low-income families who work on the surrounding farms and ranches. Some students were left on their own to navigate distance learning while their parents worked, and others had close relatives fall seriously ill from Covid. Everyone had to grapple with inconsistent and unreliable internet service.

Rogers was eager to invest in something that would bring students some joy and make them want to come to school every day. Created by the nonprofit Collaborative Classroom, SIPPS focuses on repetition and patterns, with students learning a few new words each day – either by memorizing the sight of the word or by sounding it out phonetically – that appear in simple, entertaining stories they’re able to read. The idea is that students know what to expect due to the repetition and gain confidence by mastering words at a level they can understand.

“It’s unified the kids. I see them looking out for each other, encouraging each other,” Rogers said. “It’s like they have a common goal. They’re being successful, and they’re being rewarded, which makes them feel good about themselves. It’s great to see. … I feel like a rock star every day.”

In Alice Campbell’s first grade class, teacher Melissa Ramirez divides the class into two groups based on their reading level for 30 minutes of SIPPS instruction every morning. One group sits at their desks and reads quietly while listening to headphones, while the other group gathers around Ramirez while she introduces them to new words and sounds using flashcards and a whiteboard.

On a recent morning, she taught them words that have a soft “a” sound, such as “water,” “talk,” “want” and “father.” She showed them a word on a flashcard, they recited it together, spelled it, then recited it again.

“I was leery at first because it’s a little complicated; there are a lot of steps,” Ramirez said. “But it’s repetitive, so it stays the same, and the kids like that because they know what to expect. Now they ask, ‘When can we do SIPPS?’”

As the year has worn on, Ramirez has noticed significant improvements in students’ behavior. They seem happier and calmer, she said, and so-called “problem” students have not posed difficulties at all.

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

Melissa Ramirez, a first grade teacher at Lockeford Elementary, gathers her students in a circle to practice letter sounds in a group setting.

Ramirez teared up when she described a girl who started the year not knowing her ABCs, but now she’s reading stories on her own.

“When you can read, it opens up the entire world,” Ramirez said. “If you can read, there’s nothing you can’t do. It’s like having a solid foundation on a house – you need that before anything else.”

Alice Campbell and her friend Scarlett Shates, 6, said reading is the best part of the school day. They love learning new things about the world and laughing along with Dr. Seuss. They also like how reading gets easier the more you do it. Scarlett’s favorite book is “Green Eggs and Ham,” she said, because of the surprise ending.

“Last year we couldn’t read that well,” Scarlett said. “But this year we’re learning new words and sounds. … It feels like it’s good for your brain and all that stuff.”

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments (7)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Debbie 10 months ago10 months ago

I retired from Lodi Unified. Many years ago the school I taught used SIPPS until we were told not to in favor of another approach. I am glad to see they are now using it again.

Norma 2 years ago2 years ago

I am glad they used the money wisely, I live to here that some districts are thinking about helping the teachers have better tools to help the students. Wondering how Antioch school district spend their funds. Lovely story ❤️

Gale Morrison 2 years ago2 years ago

Great story! Access to literacy is social justice for all.

Maria 2 years ago2 years ago

Beautiful story! Great job from the teachers and students. I wonder if there are other schools in CA doing the same?

Susan Rosa 2 years ago2 years ago

Striving for excellence will always bring good results. Getting rid of AP classes and not challenging students will prove disastrous for our country and future.

Donna Thayer 2 years ago2 years ago

I proudly worked as a brand-new site administrator in Lodi USD for nearly four years. It is a phenomenal district that promotes excellent teaching and high achievement. I am forever grateful for my years there, as they provided the foundation upon which my career as an administrator was built. So I am not at all surprised at these achievements.

Jim 2 years ago2 years ago

Congratulations to Lodi Unified. Reading comprehension is the most fundamental skill taught in school.