Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

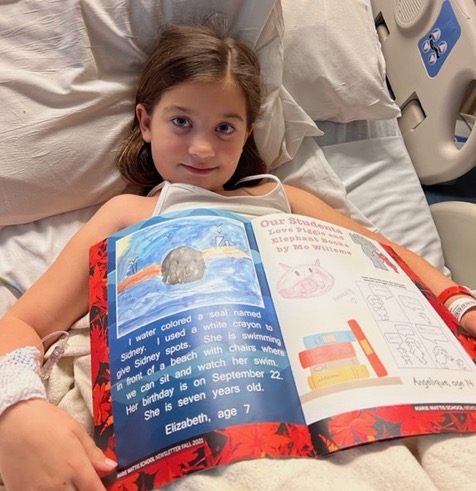

Elizabeth Madole, 8, is a regular at UC San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco. At least once a month, she and her family trek from Redding so she can get transfusions to treat a rare neuromuscular disorder.

It can be a painful, difficult time. But amid the IV tubes and machines, there is one bright spot: Miss Erika.

“We read ‘Narwhal and Jelly’ books. We do art. I like doing math, too,” Elizabeth said. “She’s just a fun teacher. … What I like best is that she loves me.”

Miss Erika — also known as Erika Shue — teaches in one of California’s most unusual public schools: the Marie Wattis School, a TK-12 school that exists within the walls of UCSF.

With an enrollment of about 80 students, the Wattis School serves children from throughout California and beyond who are grappling with serious health conditions such as cancer, spina bifida or cystic fibrosis — but who also want a “normal” school experience. Students learn geometry and history, do poetry slams and celebrate graduations, and even have a prom.

In a world where almost nothing resembles a normal childhood, the Wattis School provides structure, a connection to peers both in and out of the hospital, and perhaps most important, hope.

“The message that students get is: School is important, we think you’re going to get better, your life will go on and you will need to learn algebra,” said Julie Pollman, the school’s head teacher and one of its founders. “In that way, school becomes part of the healing process.”

Many large children’s hospitals offer education services, but UCSF’s, founded in 1992, was among the first and has served as a model for other in-patient facilities. It’s unique in that it’s part of San Francisco Unified. Of the school’s 11 teachers, four work for the district and seven are funded by private donors.

Courtesy Stephanie Madole

Elizabeth Madole, 8, shows her artwork that was published in a UCSF magazine.

As medical technology improves and more children are surviving conditions that once might have been fatal, more children’s hospitals are offering or expanding education services — an effort to make children’s transitions back to regular school as seamless as possible.

But there’s a broad range of what hospitals offer. Some children’s hospitals, like UCSF, are affiliated with school districts. They have classrooms, 1-to-1 bedside instruction, visits from science museums, room for siblings and close contact with the children’s regular teachers. Others have more informal arrangements, such as tutors who help with homework assigned by the regular school. And some, especially those that are underfunded or in remote locations, offer little or no education for their patients.

The Hospital Educator and Academic Liaison Association, a nonprofit organization representing hospital-based teachers, is advocating for more hospitals to invest in school services for children, and for credential programs to train teachers in the special art of educating children with serious health conditions.

And it is an art. Only about 35% of the children at UCSF have individualized education plans or 504s, meaning that they’re enrolled in special education, but they might tire easily, or become frustrated or depressed, or just have off days. A good teacher knows when to push the child and when to put the textbook down for a while.

Teachers at the Wattis School study children’s medical charts and talk to doctors and families, making an effort to understand what specific challenges a child might be facing on a particular day.

“Our teachers are part surrogate parent, chaplain, confidante. They know how to be good listeners, how to read body language and take the long view,” Pollman said. “You never know what kind of day your student is having, what news they just received. It might be time to celebrate, or it might be time to exert some sensitivity and put the algebra away for now.”

In some cases, schoolwork and time with teachers might actually help children recover, said Jodi Krause, a board member of the association and brain injury education coordinator at Children’s Hospital Colorado. With brain injuries, for example, academic challenges and 1-on-1 time with teachers can play a role in rehabilitation. And the social benefits of school can improve a child’s mental health overall, leading to easier hospital stays.

“A kid’s job is to be in school,” Krause said. “And we haven’t done our job if we haven’t prepared them for how they’re going to be spending their time after they’re discharged.”

Schools within hospitals have another benefit: they reduce absenteeism. Students who are learning even when they can’t physically attend their regular school have higher attendance rates overall and do better academically in the long run, Krause said.

At UCSF, students can be enrolled for just a few days for one-time procedures or, if they have chronic conditions, for years. Some even graduate from the Wattis School and go on to college. They come from throughout California and overseas, drawn to the hospital’s cutting-edge trials and research.

Elizabeth, who’ll start third grade this fall, has been a regular visitor to UCSF for years. Diagnosed with a neuromuscular disease called generalized myasthenia gravis as well as an autoimmune inflammatory disorder, Elizabeth visits UCSF at least once a month for infusions of antibodies and other treatments.

Her mother, Stephanie Madole, said that Elizabeth loves her teacher so much she actually looks forward to the long drive from Redding and the days hooked to IV drips.

“The school is phenomenal,” Madole said. “It allows her not just to continue her education, but it gives her a sense that the hospital is a home-away-from-home. The teachers care so deeply about the kids. … I don’t have the words to describe the positive impact it’s had on Elizabeth.”

Thanks to the attention she gets from Shue, Elizabeth is even a little ahead of her peers at her regular school. For children who are in and out of hospitals, that’s not usually the case. Shue allows Elizabeth’s younger sister, Charlotte, as well as Gracie, one of Elizabeth’s friends from home, to join in the lessons virtually.

“The gratitude we feel is immense,” Madole said. “Elizabeth truly feels loved.”

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Comments (3)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Thomas Edwards 2 years ago2 years ago

Elizabeth is my granddaughter as is Charlotte Grace. Stephanie is my daughter. I was extremely pleased to see how much Elizabeth has got from her in hospital schooling. It’s awesome that she looks up and respects her teacher so much. She is well above any school that she could attend up at home. Thank you for being there for the entire Madole Family

Larry Wiener 2 years ago2 years ago

I am a home and hospital teacher for a school district in California. I fully agree with the premise that a proper education contributes to recovery. I have been doing this for 19 years and have taught everything from kindergarten to 12th grade. Most of my students are serviced at their home. Many are out of school because of mental health and behavioral issues. While most of my students do not have IEPs, I make … Read More

I am a home and hospital teacher for a school district in California. I fully agree with the premise that a proper education contributes to recovery. I have been doing this for 19 years and have taught everything from kindergarten to 12th grade.

Most of my students are serviced at their home. Many are out of school because of mental health and behavioral issues. While most of my students do not have IEPs, I make it a point of adjusting the curriculum so that that students will thrive once he or she is finished with Home Hospital teaching.

Thank you for the article.

JAMES C HOCH 2 years ago2 years ago

Great article. Education is hope for the future.