Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

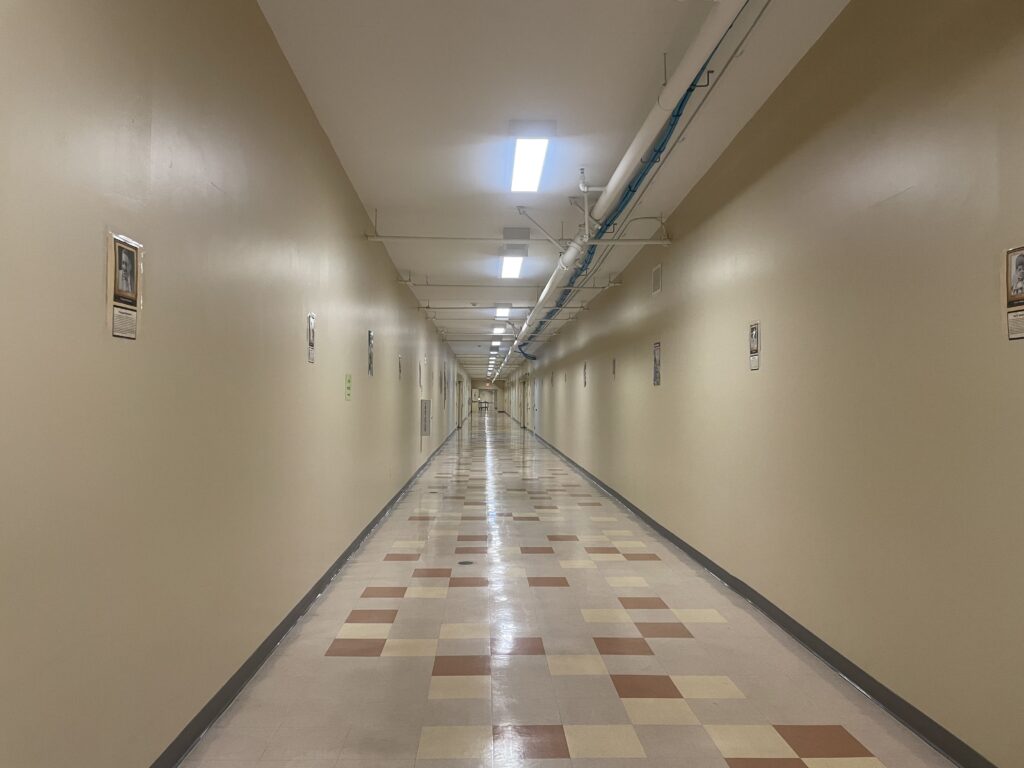

Through four heavy, locked doors, down a long beige hallway lit by bright artificial lighting, and past several locked rooms filled mostly with middle and high school students sits a room that feels far more inviting: a superhero-themed library with colorful furniture and enlarged, vibrant, culturally-inclusive artwork on the walls.

On a recent Tuesday morning, seven students were escorted to the library from room two, each of them dressed in khaki-colored pants, black shoes, bright green tees, and dark gray sweatshirts that all read the same stamped text: Alameda County Juvenile Probation.

Photo: Betty Márquez Rosales/EdSource

The hallway that connects each room inside the Alameda County juvenile hall.

The library staff waiting for them work for the Alameda County Library. They’re part of an innovative partnership between the county’s library, probation department, and office of education, which is in charge of the education of students inside juvenile halls.

What began as a volunteer program for UC Berkeley students to read with and mentor youth during the school year has since flourished into a year-round collaboration with permanent staff trained to teach literacy. It is unclear how many juvenile halls offer such resources, but at least two other counties in the San Francisco Bay Area now have similar partnerships with their local libraries.

At the Alameda County facility, called the Juvenile Justice Center, where youth reside while awaiting a court appearance or after being adjudicated, the program offers a library room, hundreds of books that are updated regularly, designated staff, and one-on-one literacy support to a population of students that has historically had low literacy rates.

“We try to make it a welcoming space that for the hour each week these kids spend in the library, they forget that basically, for all intents and purposes, they’re in jail,” said Lisa Harris, who is in charge of the library program at the juvenile hall.

Harris and her staff achieve this with a focus on connecting with the students first, reading second. Many of the students they meet are several grade levels behind in reading, and some have left school altogether. This means that the library might be one of the few spaces at the juvenile hall where they can learn to enjoy reading and educational conversation without the pressure of tests, grade scores, and credits that they would need to graduate from high school.

In short, the goal is to get the students to fall in love with reading and learn to connect with others in a healthy manner, so they may remain open to it long after they’ve left the juvenile hall.

County juvenile halls in California temporarily house young people ages 12 to 18 who are either awaiting their court date after being arrested or who have been adjudicated. Some youth spend only a few days inside, years for others.

Youth are divided up into groups and placed in rooms called units, where they have a classroom, their sleeping area, and a section for eating and hanging out. Their grouping depends on a few factors: age, what they have been adjudicated for, potential gang affiliations, etc. Due to these factors, there could be 12-year-old and a 16-year-old learning side by side, for example.

Photo: Betty Márquez Rosales/EdSource

Alameda County Library staff covers over any writing that students make on the books they check out of the juvenile hall library.

Alameda County’s hall is called the Juvenile Justice Center, and there are typically between 50 and 70 students inside, mostly boys, according to Monica Vaughan, the chief of schools for the county office of education.

In recent years, 100% of students at the hall have been considered “socioeconomically disadvantaged,” the majority have been Black boys, and over 30% have had learning disabilities, according to a 2020 independent inspection report conducted by the Alameda County Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention Commission. There are often English learners as well, which is why the library staff includes Raul Rodriguez, who has worked in the literacy world for decades and connects with the Spanish speakers in their native language.

The same report shows that 66% of students did not return to their school upon their release, though this number includes students who had dropped out prior to their arrest.

After being greeted with fist-bumps by three library staff, the students dispersed across the small room. The first few walked directly toward the closest bookshelf to flip through books in the “African American Fiction” section, others went to the opposite side toward the poetry section, and two sat across from each other at a table with a chess set in between them.

What happened next during the game of chess is perhaps the best example of why this library matters.

One of the students knew how to play chess while the other didn’t. The student who seemed to be no older than 13 grew increasingly frustrated with the game. He was hurried at times by his opponent, and a library staff person offered a printed guide to the game.

That seemed to exacerbate the issue. This group of students had been at the hall for less than 10 days, so the staff didn’t know each student well enough yet. The student began raising his voice and cursing, frustrated by the lack of knowledge with the game. The library staff and the three probation staff in the room — they remain with students at all times — asked him each time not to use curse words.

Not long after, he rose abruptly and loudly from the table, causing the staff in the room to turn their attention to them. A quick rise in emotions has led to fights in the past, staff later shared.

Photo: Betty Márquez Rosales / EdSource

Students enjoy playing chess when visiting the library.

Instead, he walked toward a chair in the back of the library, with Harris, who comes from the Alameda County Library, closely behind.

“Alright, talk to me,” Harris said to the student, crouching down to be at eye level with him.

“I don’t even know how to read, I don’t know why I even came here,” he exclaimed, still upset as he asked for permission to return to his unit.

A student outright saying they can’t read is rare, Harris later said.

Typically, they look for indicators: a student who consistently rejects reading material regardless of topic; requests specific books but can’t remember titles; flipping through books with few words and very large font size.

Some students are avid readers. One recently requested a book on quantum physics while another regularly goes through nearly ten books per week.

But for the students like the one who told Harris he can’t read, one-on-one support is required to catch them up to their grade level and age. Typically, that would mean bringing in Cyrus Armajani, a literacy specialist and Alameda County Library employee who divides his time between the juvenile hall, the county’s juvenile camp, an Oakland continuation school, and a local church that offers literacy support.

For each youth who joins, Armajani conducts a series of assessments ranging from phonetics to oral reading decoding to reading comprehension. If the student has an Individualized Education Program, which outlines the special services needed based on the student’s ability, Armajani would then join the meetings meant to keep the student on track. Perhaps, one of the county office of education paraeducators, education staff who are assigned specific students to work with, would also assist with one-on-one support.

But there’s a challenge: this specific student was recently arrested, and the library staff has no way of knowing how long he will remain at the juvenile hall, or if he’ll stay at all. It depends on the outcome of his court date, which they also don’t know exactly when it’s scheduled.

Such interruptions are persistent, according to staff. Sometimes they happen during library hours, like a student having just entered the library when he’s called away for an appointment elsewhere.

Or it may happen right when they feel they’re making progress in connecting with a student. Armajani tries assessing students’ reading ability when they are first referred to him and right before they’re about to leave. But the probation aspect of the student’s life is outside of his purview.

Abrupt endings to academic time at juvenile halls are common, according to staff and administrators across the state.

“That is one of the biggest challenges of teaching at a court school,” said Vaughan, referring to the schools for students in the justice system. “Knowing in advance would be advantageous for us to know, but we don’t always know. Sometimes we get a student for a week, and they are gone. And so what you wouldn’t be able to do during such a short period of time like that is really measure academic growth in any kind of real way, so that is a challenge.”

Photo: Betty Márquez Rosales / EdSource

Library staffers emphasize the importance of culturally relevant reading material.

The average student at the Alameda County hall is 16 or 17 years old, but their reading skills tend to be around the sixth and seventh grade level, she added.

And Armajani, who has a master’s degree in education with a reading specialist credential, has found that most of his students are at a 10th through 12th grade level in terms of oral reading, but anywhere from upper elementary to middle school with reading comprehension.

“What I do see is, despite everything they’re going through, traumas both caused and experienced, there is a desire to learn on the students’ part,” he said. “They want opportunities to express themselves and they’re intellectually curious.”

The second group of students on that recent Tuesday arrived at 1:20 pm. Just two of them, they knew to wait for some chips, their treat for the day, and sit for a movie they’d been promised during their previous visit. A movie about the death penalty, “Dead Man Walking,” began playing on the projector screen at the front of the library. One student was invested in the plot and answering comprehension questions that Harris posed.

The second student wandered toward the section with books in Spanish, flipping through several. The Spanish-speaking literacy staff, Rodriguez, walked over to help him choose one, and they soon landed on one titled, “Quien es Martin Luther King Jr.?”

Meanwhile, a faulty internet connection had paused the movie. Harris takes this moment to suggest a book for the student who’d been watching — “The Four Agreements: A Practical Guide to Personal Freedom (A Toltec Wisdom Book)” by Mexican author Don Miguel Rodriguez.

Eventually, the movie played again.

“Don’t let this stop you from reading the book,” said Harris to the student watching it.

“I still will,” the student responded. “The book is always better.”

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.