Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

“[Libraries] are cathedrals of the mind; hospitals of the soul; theme parks of the imagination,” writes Caitlin Moran, implying that literacy is more than just an academic skill, that access to books is critical.

Indeed, we know that two-thirds of children from low-income households have no books in their home, that their neighborhoods have such poor access to bookstores and libraries that they have become book deserts.

On the other hand, children with at least 500 books in their home complete three additional years of education beyond their peers. It would be costly to place 500 books in each home; libraries are great alternatives.

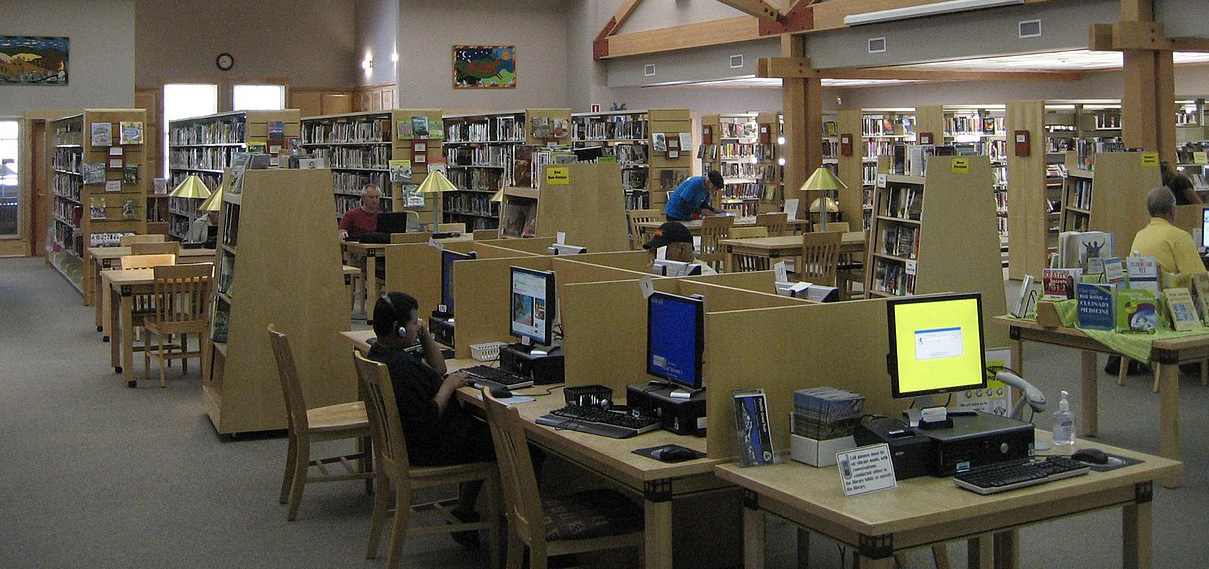

While classroom libraries offer the best access and public libraries offer the greatest variety, school libraries offer the best of both worlds: convenient access to a wide range of materials for both pleasure reading and curriculum support.

School libraries are now so much more than books. They offer board games and video games, podcasting equipment and green screens, yoga mats and exercise bikes. They have evolved into learning labs —complex, innovative spaces that leverage student engagement, peer relationships and community partnerships to create progressively immersive learning experiences that also feed the mind, soul, and imagination. Nobody says it better than Ta-Nehisi Coates: “The classroom was a jail of other people’s interests. The library was open, unending, free.”

Indeed, no other site-based program can so adeptly facilitate and synthesize such a wide range of district initiatives: career technical education, community schools, culturally relevant teaching, expanded learning, social-emotional learning, universal design for learning — and more.

This symbiotic relationship between physical space, library resources and innovative programming cannot happen without a dedicated team of library staff, a certificated teacher-librarian and a classified library technician. The former regularly collaborate with classroom teachers to design research units, infusing the curriculum with choice and relevance. The latter provide an array of highly specialized skills that keep the library running. Increasingly, both positions are subject to budget cuts. After all, classified staff are cheaper than certificated staff, especially if hired part time without benefits.

The California Education Code requires school districts to provide school library services, mandates that some library services can only be provided by a teacher-librarian and allows districts to contract with county offices of education to provide those services. To provide additional guidance, the State Board of Education adopted model school library standards in 2010 that prescribe both curricular grade-level standards for information literacy and recommend minimum levels of staffing, access and resources.

In 2016, the California state auditor presented a report on the status of school library services. The report examined statewide data and case studies in three districts and their respective county offices of education. The findings were discouraging. The library standards, for example, recommend one teacher-librarian for every 785 students; the national average was one for every 1,109 students, but the California average was one teacher-librarian for every 8,091 students—easily the worst in the nation.

The legislative response to the audit was Senate Bill 390, a bill that required districts to explicitly address library standards in their accountability plans. Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed the bill in 2017, claiming it was unnecessary, and yet here we are at the end of 2021 with new data that reveals California’s library staffing continues to drop precipitously; it may now be as low as one teacher librarian for every 23,570 students. Clearly, local control is not working for school libraries.

In retrospect, SB 390 was not an ideal remedy. The most troubling aspect of the audit was that two of the three county offices of education not only lacked the capacity to support their districts but lacked a fundamental understanding of the value of school libraries, teacher-librarians and information literacy.

The California State System of Support guides schools, districts and county offices of education as they strive to continuously improve equitable outcomes for students. Lead agencies are often designated to provide technical expertise in a variety of areas such as English learners, special education, literacy, equity and more. Would it make sense to establish a school library lead?

A school library lead could build statewide capacity by addressing the following priorities:

With a historic budget surplus on the horizon, an investment in school libraries can transform them into the cathedrals, hospitals and theme parks our students need — and deserve.

•••

Jonathan Hunt is a coordinator of library media services at the San Diego County Office of Education.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Richard Moore 7 months ago7 months ago

Accreditation. WASC asks, do you feel good about your school? 49 other states tell the school, if you don't have certificated school librarian, we will shut you down. Your four suggestions will have no effect on CA. Look me up online -- lots of info is there. Read it. Ask Krashen. Ask Rebecca Constantino. Read 30 years of my writings. Read the Rafferty Report. Read the Honig Report. But … Read More

Accreditation. WASC asks, do you feel good about your school? 49 other states tell the school, if you don’t have certificated school librarian, we will shut you down. Your four suggestions will have no effect on CA.

Look me up online — lots of info is there. Read it. Ask Krashen. Ask Rebecca Constantino. Read 30 years of my writings. Read the Rafferty Report. Read the Honig Report. But don’t think you can write one article and effect change.

Cynthia Torres 2 years ago2 years ago

A decade of budget cuts in California have left our school library services in tatters. Even districts that prize music and performing arts have been willing to cut credentialed teacher-librarians. Classroom teachers should not be expected to act as librarians, and clerks should not be saddled with the responsibility of running the school's library. Instead, teacher-librarians should be brought back to our schools to do what they do best: encourage a love of reading and … Read More

A decade of budget cuts in California have left our school library services in tatters. Even districts that prize music and performing arts have been willing to cut credentialed teacher-librarians. Classroom teachers should not be expected to act as librarians, and clerks should not be saddled with the responsibility of running the school’s library.

Instead, teacher-librarians should be brought back to our schools to do what they do best: encourage a love of reading and literature in our students. In our information age, it is critically important that our students are educated in how to use and access information.

To attain the goal of college and career readiness for our students, school libraries can serve as the center of teaching and learning. Students should be able to evaluate and integrate information, rather than simply know it. Strong school library programs are the key to assisting students to become knowledgeable users of information and technology, and to prepare them with enhanced critical thinking and research skills.