Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Students across California who speak another language at home are starting to take tests this month to see how well they are learning English. For many students it will be the first time they’ve been tested in two years.

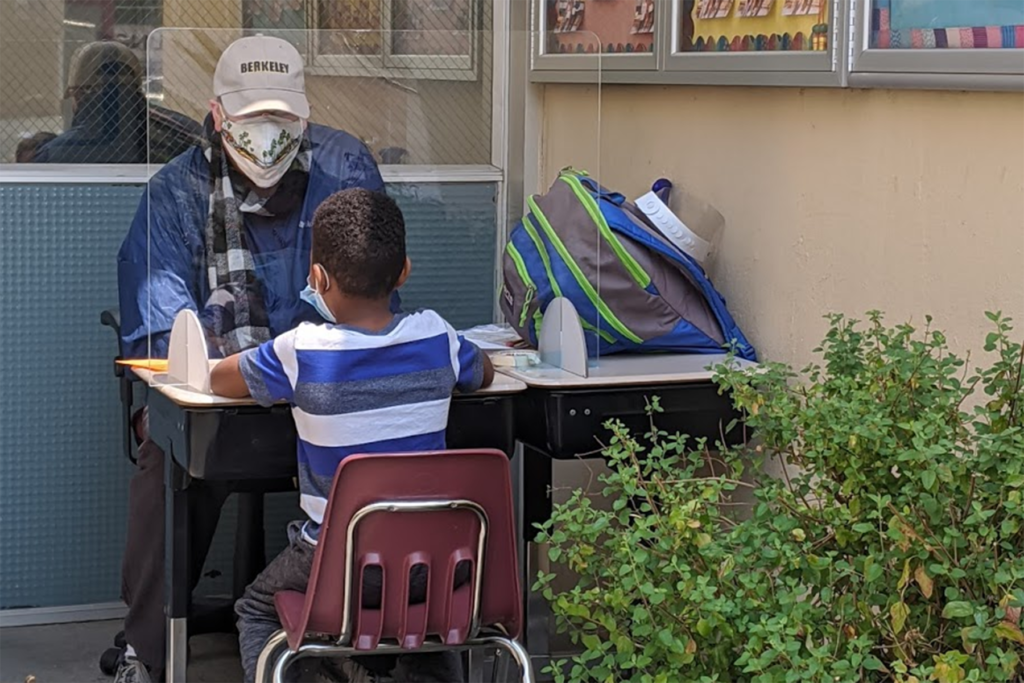

Due to the pandemic, last year the federal government did not require states to test and report English learners’ language skills. But this year, the federal and state governments are proceeding with the test, even though the pandemic is far from over.

If some students are not tested for the second year in a row, teachers and district officials worry they may not know how much English learner students have progressed over the last two school years. That could affect schools’ ability to give students the classes or other language help they need, and it could affect districts’ ability to evaluate how well different programs teach students English.

“It means we’re really not clear on how we’re serving those students and what kinds of language services they might need,” said Nicole Knight, executive director of English Language Learner and Multilingual Achievement at the Oakland Unified School District.

Close to 1 in 5 students in California public schools — about 1.1 million — are considered English learners. Schools are required by state and federal law to test students on their level of English proficiency, if they speak a language other than English at home. The test is given to English learners every year, until they achieve a high enough score to be considered fluent in English. English learners also take other standardized tests that all students take, such as the Smarter Balanced assessments in math and English.

The English Language Proficiency Assessment for California has four parts, used to test students’ ability to speak, listen, read and write in English. It can take from one to three hours to take the test, depending on grade level.

When the Covid-19 pandemic forced most schools to close their doors for in-person learning last March, almost three-quarters of English learners in California had either not yet taken the test or not yet finished all portions of the test, and the test was waived for them for the rest of the school year.

In the fall schools usually only test new, entering students for English proficiency. But this year schools also had the option to test students who had missed the opportunity to take the test in the spring. Less than 4% of continuing English learners in the state took the test in the fall.

This spring, parents can choose between having their children take an online test or an in-person test. But as school staff throughout the state begin to test students again this month and through May, there is some concern among district and county education officials that obstacles will remain.

“For me it was a civil rights issue,” said Lydia Acosta Stephens, executive director of the Multilingual Multicultural Education Department at Los Angeles Unified School District, who pushed for a remote testing option. “A lot of kids were going to be left behind, or not in the appropriate coursework they needed to be.”

Mireya Pacheco’s daughter was one of the students who was affected. Pacheco, who lives in Pacoima in Los Angeles County’s San Fernando Valley, speaks Spanish at home. Her daughter was on track to be reclassified as fluent in English last year, when she was in fifth grade, but because tests were canceled during the pandemic, she continues to be classified as an English learner. Pacheco felt her daughter was not getting enough help in English when campuses closed last spring. She is eager for her to be reclassified as fluent in English, so that she does not have the stress of having to take the test every year.

“I worry because every year the test is harder, and she has to read longer, more difficult texts,” Pacheco said in Spanish.

Her daughter now switched to a different school and is attending tutoring in person to help her prepare for the test, Pacheco said.

One of the biggest obstacles to testing students during the pandemic is scheduling, whether the test is done at home or online. When school is in-person, teachers and staff schedule tests during the school day and pull children out of class to take them. The test is federally mandated and parents cannot opt out. But with most students taking classes from home, staff have to schedule tests with parents and guardians, many of whom are unfamiliar with the English test or why it is important. Some parents have also been afraid their children might be infected with Covid-19 during in-person testing.

“There is not a day that goes by that I don’t hear from a teacher that has heard from a student about how Covid has affected them — a death in the family, a caretaker hospitalized. That has to be taken into account when scheduling an assessment. That absolutely impacts testing. It impacts everything we do as educators,” said Ruth Baskett, project director for the Multilingual Academic Support Unit at the Los Angeles County Office of Education.

School officials said it is critical to talk with students and families, answer families’ questions, explain how test results can help schools serve students better and go over Covid-19 protocols.

“The challenges that we’re faced with have really surfaced the importance of that relationship — investing in working with your parents, getting them familiar with what’s happening,” said Ruth Baskett, project director for the Multilingual Academic Support Unit at the Los Angeles County Office of Education.

The conversation with parents has to go beyond the test, Baskett said, because staff who are scheduling or giving the test need to take into account families’ specific circumstances. For example, she said, the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on low-income immigrant communities has made it harder for many students to participate in classes and tests.

“There is not a day that goes by that I don’t hear from a teacher that has heard from a student about how Covid has affected them — a death in the family, a caretaker hospitalized. That has to be taken into account when scheduling an assessment. That absolutely impacts testing. It impacts everything we do as educators,” Baskett said.

Some district officials worry that if staff who are trained to administer the test are infected with the virus, it will make it harder to finish testing all students.

“One district official I spoke to said, ‘This is what the plan is today, but at noon it could be different. We have one person testing, and we don’t know if that person might get sick,’” said Alesha Moreno Ramirez, staff development and curriculum specialist for language development at the Tulare County Office of Education, in the Central Valley.

Many district and county education officials praised California Department of Education staff, who they said have listened to concerns and made changes in how the test is administered when students take it remotely. For example, originally the test could not be taken on an iPad, yet many districts have distributed iPads to younger students. Now, iPads can be used. In the fall, younger students were expected to complete the written portion of the test in a paper booklet and return it to the school. Now, the education department is allowing students to write responses on a whiteboard or a piece of paper and hold them up to the screen to show the person giving the test.

Technology and internet issues have presented the biggest hurdles for remote testing of English learners. Many families did not have high-speed internet in the fall. Others did not have computers. Most districts have made an effort to get students computers and Wi-Fi hot spots, so they can access the internet from home. Still, some district officials are worried internet glitches will still be a problem, because not all families have high-speed internet with enough bandwidth to accommodate multiple students in one household.

The technology is a particularly steep hurdle for kindergartners and others who may have never used a computer or another digital device.

“When we think about newcomers, many are coming from the highlands of Guatemala, and they have come from areas without internet, or they may be using computers for the first time,” Knight said. In addition, she said there has been some misinformation that feeds into immigrant families’ fears about detention and deportation. “There’s this whole landscape of anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric, of what families are understanding when they’re told they have to come in to take an English test.” Knight said in one school, a false rumor circulated that families should not respond to messages from the school about an English exam, because it was supposedly a scam.

The technology is not only new to many students, but also to many teachers. This spring will be the first time most older students will be taking the test entirely on a computer, whether they do so in a school setting or remotely.

“Not only do educators have to learn a new way of administering the assessment through the computer, they also have to learn how to potentially administer it remotely. This has many educators along with family members concerned with how students will respond to the assessment as well as with the validity of the results,” said Robert Meszaros, a spokesman for the Kern County Superintendent of Schools.

Some education officials are hopeful that with the challenges administering the English language test this year, schools will pay more attention to other ways they can measure students’ progress in English. And district officials are proud of how teachers, families and students have come up with ways to clear the hurdles that have come up. In Los Angeles Unified, for example, some older students, eager to take the test, asked if staff could test them at night, so they could have a quiet time after school, work or taking care of younger siblings.

“There was an advocacy from kids themselves, which I was really thrilled to see,” Acosta Stephens said.

Panelists discussed dual admission as a solution for easing the longstanding challenges in California’s transfer system.

A grassroots campaign recalled two members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Nancy 3 years ago3 years ago

As a teacher of first grade students in a low SES community that has been ravaged with death, homelessness, and even deeper poverty levels, administering a high stakes test to 5 and 6 years is a cruel and unusual punishment during a pandemic! I know the English level of each of my ELL students and how much progress they have made this school year. If you want to know, just ask me!!

Renae Bryant 3 years ago3 years ago

Absolutely ridiculous! It’s not a “civil rights” issue to suspend high stakes standardized testing for another year. It’s a human rights issue to force students suffering social-emotionally to take high stakes standardized assessments as they have family losing jobs and family members hospitalized and dying from COVID. ETS was so strict about the testing atmosphere in classrooms for high stakes standardized tests. Now somehow it’s appropriate to allow students to take these tests from hotel … Read More

Absolutely ridiculous! It’s not a “civil rights” issue to suspend high stakes standardized testing for another year. It’s a human rights issue to force students suffering social-emotionally to take high stakes standardized assessments as they have family losing jobs and family members hospitalized and dying from COVID.

ETS was so strict about the testing atmosphere in classrooms for high stakes standardized tests. Now somehow it’s appropriate to allow students to take these tests from hotel rooms, or while providing childcare while their parents are working or while suffering during a pandemic!?! Is it fair to make students take this test with shoddy internet and multiple students in one room using one hotspot? How can we consider any of these high stakes standardized test results to be either fair or valid in these circumstances? This is ludicrous!

Why don’t we spend the time we would have spent testing to teach social emotional and mental health lessons?

Anyone prioritizing high stakes standardized testing right now needs to check their privilege!