Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Instead of $3 billion more in funding next year, officials from Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration are now projecting possibly $18 billion less over two years for K-12 and community colleges. That amount — a historic decline of more than 20 percent in the constitutionally guaranteed minimum level of funding — would have a devastating impact on education, unless Newsom and the Legislature take other actions to reduce the cut or lessen the impact.

The California Department of Finance released revenue and funding forecast on Thursday, a week before Newsom is expected to release his revised state budget. Financial data reveal the shattering and immediate impact of the coronavirus on the state’s economy. With more than 4 million Californians out of work and applying for unemployment insurance, forecasts project a drop in sales and incomes tax receipts by more than 25 percent next year.

With health and human services caseloads and COVID-19 expenses to cost $13 billion and state revenues to fall $41 billion, the state will face a $54 billion budget deficit for 2019-20 and 2020-21, according to the forecast. The General Fund would plunge to under $100 billion, the level it was in 2011-12, the tail end of the Great Recession.

Education officials are not expecting Newsom to force an $18 billion cut on school budgets. That would be the impact if Newsom funded only the minimum level required under Proposition 98, the formula that determines the portion of the General Fund that goes to K-12 and community colleges.

In his March 13 executive order, Newsom promised to fully fund districts and charter schools for 2019-20, holding them harmless at the Prop. 98 level that the Legislature passed last June, as long as they provide distance learning, meals for low-income students and child care for essential workers. He hasn’t indicated he’d renege on that promise. Next year’s funding, when the full brunt of the recession will be felt, is what is endangered. (Go here for the fiscal update and here for the PowerPoint from the Department of Finance. The Proposition 98 forecast is on page 8 of the PowerPoint.)

In addition, there are other ways to mitigate the impact of a funding cut: through deferrals, which are late payments from the state, relief from increases in districts’ employee pension payments and funding schools beyond the minimum — an argument school officials will make, pointing to the effects of campus closures on district expenses and children’s learning.

“The governor understands that districts and community colleges cannot absorb a cut of that magnitude, which will eviscerate schools,” said Kevin Gordon, a Sacramento-based school consultant. “The notion of cutting schools deeper than any reduction in school history doesn’t seem reasonable in an election year.”

“These cuts would undo the last six years of progress we have made on school funding. Our schools cannot endure another blow following this Coronavirus crisis,” California Teachers Association President E. Toby Boyd said in a statement. “We are painfully aware that the state and county are facing a recession, but for years California students, schools and educators have had to do more with less and we can’t let our students fall further behind.”

California Community Colleges Chancellor Eloy Ortiz Oakley promised to work with Newsom, the Legislature and others in the college system to get through the crisis while warning that the state must not allow a repeat of what happened during the Great Recession.

“Severe budget cuts to higher education at the time forced community colleges to turn away 500,000 students, allowing California to fall further behind in the production of college-educated workers and hindering economic recovery,” he said in a statement. “California needs to continue to invest in community colleges, which are educating nurses and first-responders battling this pandemic and which will educate workers for the state’s economic rebound.”

A grassroots campaign recalled two conservative members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Comments (13)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Hans 4 years ago4 years ago

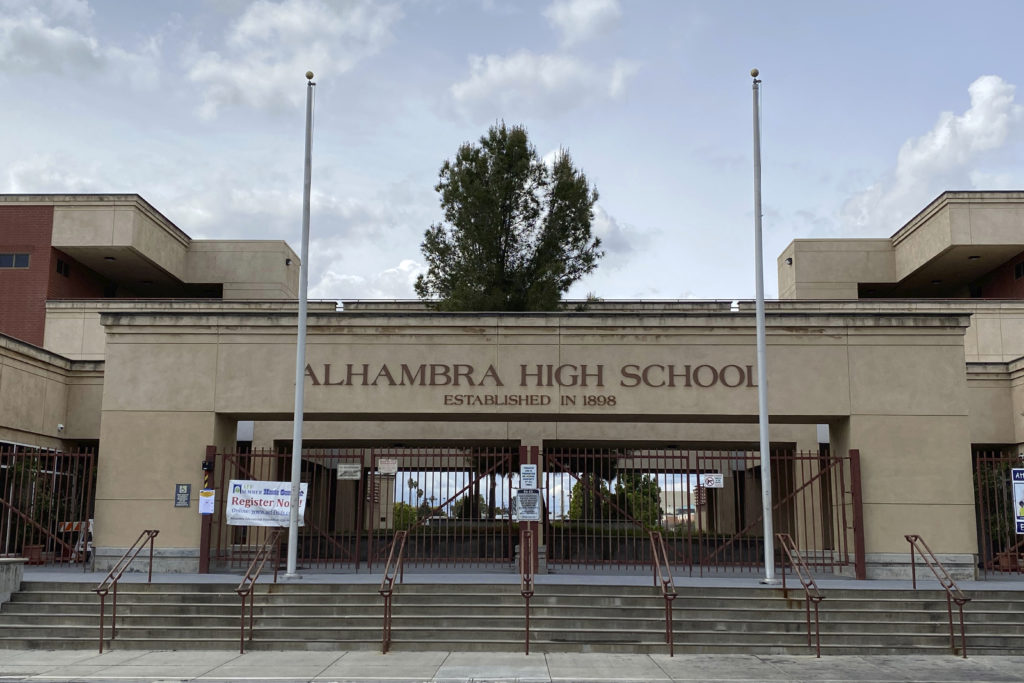

The photo in the article is my high school!

Mary Jane Dumais 4 years ago4 years ago

I’d like to hear that if teachers have to take a hit on salary that we hear our elected officials also take a hit. Teachers are clearly underpaid considering the education they have to have which is on-going even after they start work. Not to mention the preparation and expenses they make outside of work. It’s my understanding that some public officials have health benefits even after they are no longer in office; they … Read More

I’d like to hear that if teachers have to take a hit on salary that we hear our elected officials also take a hit. Teachers are clearly underpaid considering the education they have to have which is on-going even after they start work. Not to mention the preparation and expenses they make outside of work. It’s my understanding that some public officials have health benefits even after they are no longer in office; they have retirement benefits that we are paying for while we have to set up an IRA account or something like that.

It must be nice to be able to establish a system where they can set these things up for themselves. Then spend our tax money on their pet projects whether we like it or not. I’ve lost respect for almost all of the politicians in our country. Very sad!

Todd Maddison 4 years ago4 years ago

So…. In your podcast interview with John Gray, the very first suggestion he makes in dealing with this shortfall is to cut from the education of our kids – by reducing the amount of time in the school year, furloughing teachers. Given the average school year is only 180 days, one would think that “sharing the burden” of this crisis among everyone might suggest perhaps simply making that reduction in cost without cutting from our kids … Read More

So…. In your podcast interview with John Gray, the very first suggestion he makes in dealing with this shortfall is to cut from the education of our kids – by reducing the amount of time in the school year, furloughing teachers.

Given the average school year is only 180 days, one would think that “sharing the burden” of this crisis among everyone might suggest perhaps simply making that reduction in cost without cutting from our kids education would be a good idea, but nope – not even suggested.

He goes on to list other things – every single one of which involves (as he admits later) – cutting from the education of our kids, not from anything that involves the adults in the industry.

Laying off teachers in August? Yup, more cuts that would affect our kids.

Increasing class sizes? Surprise – more cuts that affect our kids.

Asking school employees to simply accept slightly lower pay and therefore save the jobs of teachers that would be laid off and provide our kids with a full school year?

Barely mentioned. And only in the context of “it can’t be done.”

Even though doing that will “disillusion thousands and thousands of new teachers” and damage the pipeline going forward as well.

Asking school employees to perhaps shoulder a more reasonable part of their healthcare expenses – as is normal in every industry outside government?

Nope. Not mentioned.

How about even doing something to finally reform the pension system to allow it to be better funded without increasing contributions?

Nada. Zip. Even though we’ve seen plenty of mention in EdSource and other places that those contributions have huge impact.

How about a serious conversation with someone on how to deal with the revenue shortfalls, including ways it could be done without cutting from our kids?

Or is that just so far from what anyone in education wants to do that it’s not even worth discussing?

Perhaps EdSource might want to be a productive part of the conversation ahead and have some discussions on how we can deal with revenue reductions in ways that do not hurt the education of our kids.

Replies

John Fensterwald 4 years ago4 years ago

Todd, it’s more accurate to say that John Gray listed options, not recommendations. As he noted, changes in pay and benefits would have to be negotiated with unions at the district level; they cannot be imposed by the Legislature. As for pensions, yes, the Legislature could change the pension benefits for new teachers; courts or voters, through an initiative, would have to weigh in on changing pension contributions for existing teachers.

Dan Plonsey 4 years ago4 years ago

We teachers are already contributing much more to healthcare and our pensions! My monthly contribution to healthcare went from $0 to $900/month over the past 15 years. My contributions to my pension went from 8% to 10% of my salary. And teachers' salaries have not kept up with cost of living. Why is it that EdSource and most of its readers would much rather bash away at greedy teachers than consider taxing the wealthiest Californians, … Read More

We teachers are already contributing much more to healthcare and our pensions! My monthly contribution to healthcare went from $0 to $900/month over the past 15 years. My contributions to my pension went from 8% to 10% of my salary. And teachers’ salaries have not kept up with cost of living. Why is it that EdSource and most of its readers would much rather bash away at greedy teachers than consider taxing the wealthiest Californians, who for decades have been the reliable recipients of pretty much all new wealth?

The rate of growth in wealth of CA billionaires has been a reliable $50 billion/year for 10 years. Meanwhile, new teachers are no longer able to buy a house. The way I see it, EdSource and many of its commenters are asking teachers and indeed all of the middle class to agree to finance the billionaires’ obscene increase. Why?

Pamela Kelly 4 years ago4 years ago

Not enough money for schools but $1 billion for masks. This doesn’t make sense.

Mary Ann 4 years ago4 years ago

Pensions are always to blame, when COLA raises for us have been 1-2% cost of living, rent, gas, etc. is way above 1% a year. School employees get a bad rap. We don’t get bonuses or Christmas bonuses, etc that normal workplaces get. Stop pointing the finger at pensions. And then cut SS too! California is outrageous with prices on everything. Mismanagement is higher up. Stop threatening the school system and workers.

Replies

Jennifer Bestor 4 years ago4 years ago

Understanding the financial fundamentals of the pension problem is critical, both for today’s teachers and tomorrow’s students. History is busily repeating itself. There will be great temptation to dial back increased pension contributions (at least those made by districts and the state) and let the unfunded pension balance grow. For the state, this growth is a form of off-the-books deficit spending. Sadly, however, the deficit doesn’t disappear when things get better. … Read More

Understanding the financial fundamentals of the pension problem is critical, both for today’s teachers and tomorrow’s students. History is busily repeating itself. There will be great temptation to dial back increased pension contributions (at least those made by districts and the state) and let the unfunded pension balance grow. For the state, this growth is a form of off-the-books deficit spending.

Sadly, however, the deficit doesn’t disappear when things get better. Someone ends up paying: either (a) tomorrow’s students and teachers (via ever-larger paycheck and district contributions, which you are experiencing now if you are a current teacher) — or (b) tomorrow’s state residents generally (in the case of a CalSTRS bankruptcy). Grimly, whoever pays is not only paying for the actual benefit, but also the lack of compound investment return that would have mitigated its cost. (If you are a teacher now, looking at your current contribution rate, you may well be galled to see people questioning pensions. You are not only covering the cost of your own benefits in the future, but helping to defray unfunded commitments to people who taught 20 years ago and contributed 25% less — teacher contributions were 8% historically vs. 10.3% now.)

An EdSource article last year (“New data detail soaring costs of California school pensions”, March 21, 2019) details how we got here — and also points out that the State General Fund is left on the hook if pension contributions fall short. Perhaps this why the teachers’ unions have allowed the pension overhang to grow, while Governor Brown and Governor Newsom have made a top priority to pay it down. In any case, the current pension fund is forecast to run out in about 25 years … leaving the state directly paying retired teachers for service now, decades earlier, rather than funding roads, education of their own young people, parks, health and welfare, etc.

How does history calibrate the temptation? Twenty years ago, the roaring stock market of the dot-com boom made it look like CalSTRS, the teacher pension fund, had enough assets to fully fund its future payout obligations. This allowed the Legislature to reduce the State’s contribution to CalSTRS while improving program benefits. Within a couple of years, the dot.com crash flipped the picture, leaving CalSTRS $20B short of its required funding. However, that crash (coupled with the Enron debacle) meant dramatic belt-tightening across all state programs. Rather than further cutting school or other programs in order to reinstate its prior contribution level — or reversing the benefit increase — the Legislature essentially ignored the situation and let the unfunded commitment grow, in a form of invisible deficit spending. By 2011, the difference between CalSTRS current assets (including their compound growth potential) and its future payout liabilities to teachers was $70B. (One could argue, by the way, that the state ‘spent’ $6B/year more on education through those years than was shown on the books — raising our ranking significantly among states in per-pupil spending.) This led to the dramatic increases in pension payments, by teachers via paycheck, by districts and by the state, but the momentum of such deficits meant that the shortfall $107B by 2017. To put this in context, the state spent less than half that — $52B — in General Fund revenue on K-12 education that year.

So here we are again. The forecast statewide deficit is horrific and the options are limited. In 2018-19, school districts contributed $8B to CalSTRS — $6B a year more than when the pension contribution increases began. The temptation to dial back some of that $6B to mitigate the $18B drop in the Prop 98 obligation will be substantial. That said, increasing contributions when the state can ‘afford it’ means paying in only at the top of the investment market … and missing any benefit from payments made before its rise.

SD Parent 4 years ago4 years ago

The funding cuts would be devastating, but so would spending money on "distance learning" or "blended learning" with zero metrics or accountability for student outcomes--which is what we're doing now and planning for the future. If CTA is worried about students falling behind, then I challenge it to do more to actually ensure student learning instead of lobbying for "guidelines" that allow school districts to negotiate MOUs that suspend teacher lesson plans and evaluation … Read More

The funding cuts would be devastating, but so would spending money on “distance learning” or “blended learning” with zero metrics or accountability for student outcomes–which is what we’re doing now and planning for the future.

If CTA is worried about students falling behind, then I challenge it to do more to actually ensure student learning instead of lobbying for “guidelines” that allow school districts to negotiate MOUs that suspend teacher lesson plans and evaluation (which allow a teacher to just hand out homework packets or post a single video a week), suspend all standardized assessments, and suspend any accountability on student outcomes (including the suspension of LCAP and School Dashboard metrics and the development of a new LCAP).

Christopher Chiang 4 years ago4 years ago

Any predictions on the impact on basic aid districts?

Replies

John Fensterwald 4 years ago4 years ago

Jennifer Bestor has offered insights on this issue, Christopher.

Jennifer Bestor 4 years ago4 years ago

Christopher, please look at the comment section of the earlier article, "The coming storm: big budget cuts, rising costs for California schools," for my detailed answer on basic-aids to your question. Also there you will find a very thoughtful and accurate comment from Amoree Cole about the "new" basic-aids that were created by the school funding cuts. (Amoree, you will have noted that I began my analysis saying that the effect on "current" … Read More

Christopher, please look at the comment section of the earlier article, “The coming storm: big budget cuts, rising costs for California schools,” for my detailed answer on basic-aids to your question.

Also there you will find a very thoughtful and accurate comment from Amoree Cole about the “new” basic-aids that were created by the school funding cuts. (Amoree, you will have noted that I began my analysis saying that the effect on “current” basic-aids … 😉 …) Property tax has historically been the most stable and reliable form of local revenue. As state income tax crashes and burns, reducing the Prop 98 obligation, the value of the property tax component of school funding becomes absolutely evident. Not only do property tax receipts arrive on time (unlike deferred state payments), they remain relatively stable, which is why districts flip to basic-aid status in downturns.

Jennifer Bestor 4 years ago4 years ago

The other shoe – declines in property tax revenue – has yet to drop. In the Governor's January budget, $1.1B of the $1.2B of K-12 COLA increase (92%) was to be covered by property tax increases. In recent years, these increases have been fueling a large proportion of the increase in school funding. If property taxes revenues recede, Prop 98 and/or stable school funding may demand an even larger share of the … Read More

The other shoe – declines in property tax revenue – has yet to drop. In the Governor’s January budget, $1.1B of the $1.2B of K-12 COLA increase (92%) was to be covered by property tax increases. In recent years, these increases have been fueling a large proportion of the increase in school funding. If property taxes revenues recede, Prop 98 and/or stable school funding may demand an even larger share of the General Fund than the 34.7% shown in the Department of Finance documents.

In a recent comment section, I noted that property tax receipts in basic-aid districts were fairly stable through the 2008 recession. Declines-in-value (reducing the assessed value and property tax bills on recently sold properties) were offset by the sales of properties that had been carrying low assessed values due to their early Prop 13 base years.

That dynamic was less evident in most LCFF-funded (revenue-limit) districts since they did not have the inducement of adequate schools to offer residential buyers. Thus, on top of the decreases in income and other tax receipts we’ll see at the state level, we could expect a $3-6 billion contraction in K-14 property tax receipts that will place additional pressure on the Prop 98 “guarantee” and/or the General Fund and/or districts. (Who it hits will be determined by whether Prop 98 is suspended, deferrals are introduced, etc.)