Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Merriam-Webster’s word of the year is pandemic, with malarkey a distant runner-up. What else could it be? Like a strangler fig, Covid-19 enveloped all aspects of life and education in California. It uprooted families, turned bedrooms into classrooms, put friendships on ice. The comforting, daily rhythms of school interrupted are now measured in learning loss and screen time. There was other big news, too — monumental protests, election defeats, new college leaders. But most of 2020, we concentrated on and tried to make sense of a virus that disrupted and transformed California schools and colleges. Here are the highlights of what we wrote.

By: John Fensterwald

Credit: Kirby Lee/AP

Overall view of the closed Arthur E. Wright Middle School sign in the Las Virgenes Unified School District amid the global coronavirus Covid-19 pandemic outbreak in Calabasas on March 30, 2020.

On March 5, a day after Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a Covid-19 state of emergency, a handful of schools in California had closed. Ten days later, after Newsom assured school districts their funding would continue, districts with nearly all the state’s students announced shut-downs, and Newsom said they should expect to stay that way through summer. Since then, there have been disappointments — Newsom predicted summer school and an early restart in the fall — dashed hopes and missed opportunities (see timeline).

In mid-July, Newsom announced that schools with 5 million students, in 32 counties with high infection rates, would likely open in distance learning. Protracted labor negotiations in large districts during a pandemic lull delayed plans. Yet on Oct. 30, EdSource reported “a clear momentum” in rural districts and in much of Orange and San Diego counties for returning to school in some fashion. Then came Thanksgiving and cold weather, and Californians let down their guard. The “momentum” to return to school buildings, with “the health system reaching a breaking point,” EdSource reported on Dec. 24, has “largely come to a halt.”

By: Louis Freedberg and Sydney Johnson

Credit: Christina House/Los Angeles Times/Polaris

Cal State University Fullerton student Linh Trinh, 21, right, and her boyfriend Tan Nguyen, 21, walk around a deserted CSUF campus on Tuesday, April 21.

On May 12, the 38-campus California State University announced it would switch to distance learning in the fall, with a few notable exceptions, a decision later extended for the year. Also affected were the 116-campus California Community Colleges system. Among the UC campuses, where some held in-person classes, UC San Diego employed aggressive testing strategies to keep students safe. CSU Chancellor Timothy White’s unwavering position to switch nearly all classes to virtual until fall 2021 gave campuses time to reach out to coax first year students to attend and prepare for the transition. It paid off: More than half of the campuses saw enrollment gains, bucking a national trend. But worries continue about incoming freshmen, many of whom had to work to help their families, described in an EdSource project: “Freshman Year Disrupted.”

By: Michael Burke, Ashley A. Smith, Larry Gordon and Betty Márquez Rosales

Credit: Del Norte Unified

Staff at Del Norte Unified deliver paper packets to students during the coronavirus pandemic.

The sudden closure of schools last spring exposed a huge digital divide that left predominately rural students and low-income children without computers and internet connections needed for distance learning. The Legislature mandated that school districts must provide them, and many districts, with corporate donations and federal funding, rushed to buy them, but by Oct. 15, the state calculated it was still shy by 1 million computers and hot spots. The law firm Public Counsel cited that failing among the claims in a lawsuit against the state on behalf of low-income children.

By: Sydney Johnson, Michael Burke and John Fensterwald

Credit: The White family

The White children study in the classroom of their Auburn home.

Learning pods became a phenomenon for the affluent, but working parents who couldn’t afford private schools in their living rooms, sought other alternatives to their districts’ remote learning. San Juan Unified saw demand for its home schooling program soar, as did Anaheim Union High School District, which created a separate virtual academy with its own staff (a topic of an EdSource webinar). Organizations like the Bay Area Parent Leadership Action Network trained parents to help one another, and Oakland REACH created a “virtual city-wide hub” for summer learning that expanded in the fall.

By: Zaidee Stavely, Diana Lambert and Theresa Harrington

Credit: AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli

Gov. Gavin Newsom gestures toward a chart showing the growth of the state’s rainy day fund as he discusses his proposed 2020-2021 state budget during a news conference in Sacramento, on Jan. 10, 2020.

The year that began with Gov. Gavin Newsom’s rosy revenue projections turned to bust by June, with billions in budget cuts to higher ed and state funding deferrals for K-12. But soaring tax revenues from a booming stock market has tempered the gloom; the Legislative Analyst’s Office is predicting a huge windfall will wipe out this year’s budget deficit for K-12 and community colleges. In March and then again in December, Congress passed billions of dollars in Covid relief, leaving school districts better off heading into the new year than observers thought possible.

By: John Fensterwald

Credit: UC/CSU

UC’s Michael Drake and CSU’s Joseph I. Castro

Two new leaders are taking charge of the state’s university systems in the middle of a pandemic and a recession. In July, the regents named Michael V. Drake, the former chancellor of UC Irvine and president of The Ohio State University, to succeed Janet Napolitano as president of the University of California. In September, the California State University trustees selected Fresno State President Joseph Castro to replace retiring system Chancellor Timothy White. Together with Eloy Ortiz Oakley, chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and state Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, for the first time, all four of the California’s public education systems will be led by people of color.

By: Michael Burke, Ashley A. Smith, Louis Freedberg

Credit: UC Davis/Twitter

The UC Davis Veterinary Emergency Response Team treated animals in August in Solano and Sonoma counties to provide veterinary care to animals evacuated by the fires.

With names like the Creek Fire and the August Complex, wildfires burned a record 4% of the state’s 100 million acres in 2020. The fresh smell of smoke was traumatic for children in Butte and Sonoma counties who had fled their homes and suffered losses before. Schools became community centers; principals, teachers and counselors, wizened by devastation, shared advice in an 84-page guide to help districts navigate natural disasters.

By: Carolyn Jones

Credit: Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times/Polaris

Billie Montague, 2, puts a vote sticker on her nose while watching her mom, Ashley Montague, vote at Marina Park Community Center on election day Nov. 3, 2020 in Newport Beach.

Polls predicted a close vote on a grass-roots initiative to raise taxes on commercial property, and it was. The “Yes” and “No” campaigns for Prop. 15 spent $140 million; it lost 48% to 52%. A ballot measure the Legislature put before voters in November to repeal a ban on affirmative action had the support of UC regents and the CSU trustees — but not voters. Backers argued, to no avail, that it would undo a wrong imposed 24 years ago. By year’s end, the focus had shifted to other ways to close the equity gaps in college admissions, such as factoring in household wealth, offering A-G courses for all and diversifying college faculty.

By: Thomas Peele, Daniel J. Willis, Larry Gordon, John Fensterwald,

Credit: Sydney Johnson/EdSource

Two juniors at Oakland School of the Arts attended the youth-led march in Oakland on June 1.

On June 1, days after a Minneapolis policeman suffocated George Floyd, 15,000 high school students and others marched through downtown Oakland — one of many protests under the banner Black Lives Matter. The movement precipitated calls for action. The Legislature agreed to evaluate the role of police on school campuses and study alternatives. Oakland’s school board voted to replace its 67-member police department with more counselors and restorative justice coordinators. San Diego State became the first CSU campus to require all criminal justice students — the major for future police officers — to take a course in race relations.

By: Sydney Johnson, Carolyn Jones, Theresa Harrington

Photo: Yalonda M. James/San Francisco Chronicle/Polaris

Alexandra Lozano watches preschooler Ivy Gold, 3, as she plays at Rockridge Little School on July 21 in Oakland.

The pandemic created a crisis for child care centers. Already operating on thin margins, with underpaid staff, thousands of family day care and child care centers closed by mid-March. Other owners racked up credit card debt to stay open with fewer socially distanced children. They were eligible for the $100 million that the state funded schools for PPE and safety expenses and for the oversubscribed small business grants under the federal CARES Act. Congress added about $1 billion for California in the latest Covid relief package to subsidize child-care costs for low-income families and children of essential workers. But the first challenge of Gov. Newsom’s Master Plan for Early Learning and Care will be to rebuild a sector that the pandemic has ravaged.

By: Zaidee Stavely and Karen D’Souza

Credit: Andrew Reed/EdSource

Ann Hoeffer (right) and her daughter Amber Scroggins (left) stand in the kitchen with three of Scroggins’ children.

“This has been like a bomb going off,” said Rashida Dunn-Nasr of Sacramento, describing the shock and chaos of the first weeks of distance learning with 4 school-age children at home. Parents overall found the early days as teacher aides disconcerting and frustrating. Since schools resumed in the fall, EdSource has reported the experiences of 16 families in a year-long project from mountain towns in Northern California to the urban hubs of San Diego and Los Angeles to the farm fields of the Central Valley. Some students have adjusted to distance learning, a few have thrived with Zoom, but many are struggling, technologically, academically and emotionally. One sixth-grader in Los Angeles with technical glitches missed six weeks of school before the district noticed. All are hoping they can return to schools and friends sometime in the spring.

By: EdSource Staff

Credit: Cindy Evans

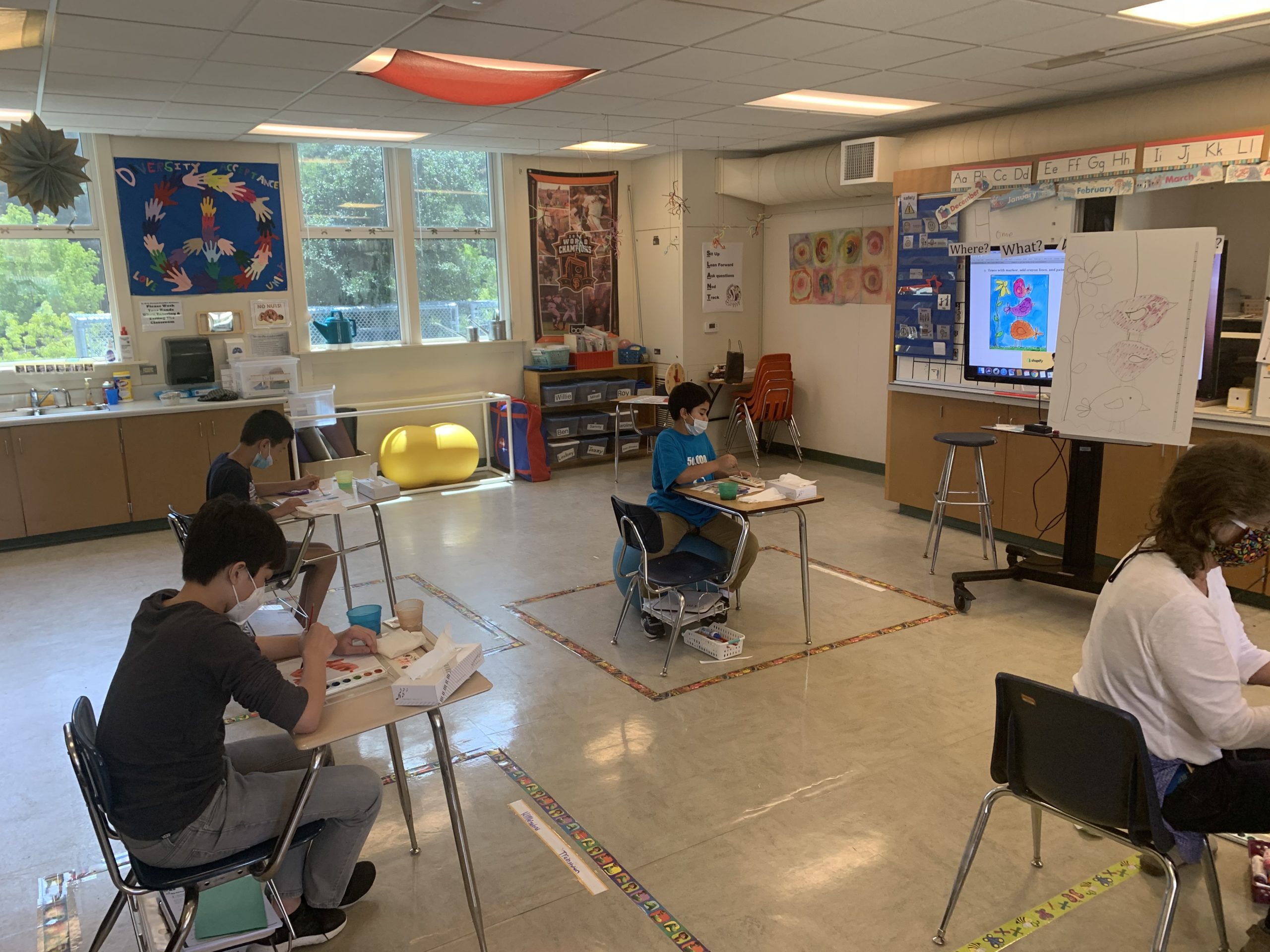

Students in a special day class at San Jose Middle School in Novato in Marin County have returned to school and are practicing social distancing

They are the students with the greatest needs, the ones identified by federal and state laws as entitled to extra services. Yet the state’s homeless and foster children, English learners and students with disabilities are often the students hardest to reach and to serve. Every day is a challenge for homeless students, who struggle for internet connections, a place to study, a bed to sleep on; and their numbers are growing. Many English learners, who make up a fifth of the state’s students, are feeling lost and isolated on Zoom, without language supports and translations for their parents. Parents and teachers of students with special needs are frustrated by challenges of remote learning. Most students with severe handicaps aren’t getting in-person therapy; many students with learning difficulties can’t cope on Zoom. Some districts were trying to improve, but parents are worried their children are fast losing ground.

By: Carolyn Jones and Zaidee Stavely

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.