Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

As California’s K-12 system ramps up to expand and diversify student access to computer science, we are drawing attention to a critical pipeline concern.

Trish Boyd Williams

California’s public higher education systems do not have the capacity now to adequately meet the existing surging student demand for Computer Science majors, a problem which will only escalate further as more K-12 students get access to computer science.

In the past 14 months alone:

Sathya Narayanan

Each of these aligned state policy levers will build K-12 momentum for bringing computer science into the curricula, which will have the effect — along with the attractiveness of computer science careers and salaries — of further increasing student interest in a computer science major in college.

But in 2017 the national Computing Research Association released Generation CS, a report documenting the surging demand by students for computer science majors in both public and private universities across the country.

Our initial look at data for California indicates this is true as well for all three of California’s public systems of higher education.

An in-depth analysis for the California State University system found that over the past decade, especially the past five to six years, there has been a dramatic surge in student interest in pursuing computer science at CSU.

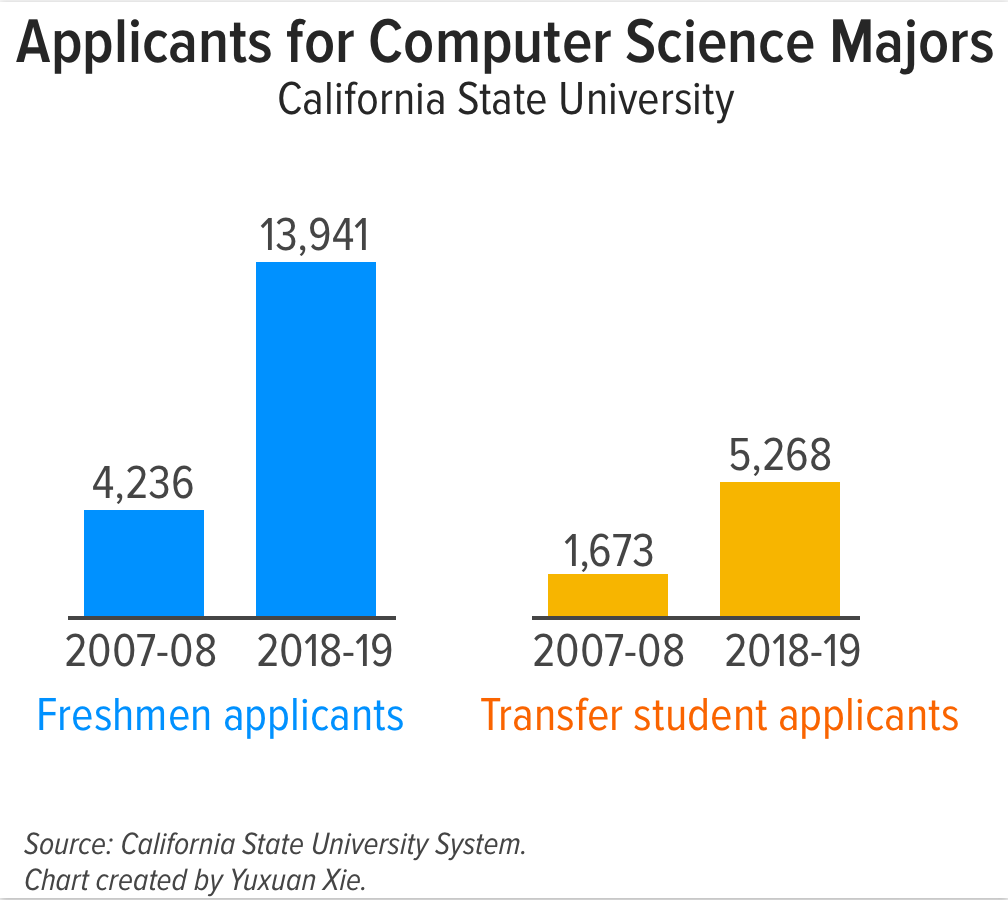

From 2007-08 to 2018-19, the CSU system as a whole has seen a 229 percent increase (from 4,236 to 13,941) in the number of first-time freshman students applying for a computer science major and a 214 percent increase (from 1,673 to 5,268) from undergraduate transfer students.

During this same decade, the CSU system has seen its total applications for a computer science major, which includes duplicate applications submitted by students to multiple CSU campuses, increase from 8,931 in 2007-08 to 44,452 (397 percent) in 2018-19.

These astounding increases in the numbers of applications reflects an increase in numbers of students wanting a computer science major as well as an increase by students submitting duplicate applications to multiple campuses because of the increased competitiveness of admission to the major.

In the CSU system in 2018-19, roughly two thirds of students applying for a computer science major were granted admission to that major, leaving more than one-third of students admitted to CSU but denied the computer science major they wanted.

Adding to the computer science capacity strain, more students from other majors are taking computing courses past the introductory level and more students are minoring in computer science.

This has the effect of making it more difficult for students in a computer science major to get the courses they need when they need them. Also, this disproportionately impacts lower income students who may be less well-prepared, preventing them from getting into and succeeding in upper division computer science courses.

In response to inadequate capacity to respond to surging student demand, criteria for admission into a computer science major at the UC and CSU have necessarily become increasingly selective. Every UC campus, and 9 of the 23 CSU campuses, has now declared computer science departments as “impacted” — restricting their admissions.

As UC and CSU increase selectivity for admissions to a computer science major (which might include requiring higher test scores, higher grade point average, more rigorous high school math courses or prior programming experience), this may further disadvantage low-income students with less access to rigorous high school curricula and computer science-related extracurricular programs.

California’s public college and university computer science capacity challenges are big, growing and complex. State funding is a contributor: between 1976-77 and 2016-17, higher education funding for all three systems combined fell from 18 percent of the state’s total budget to 12 percent.

Departments also have the challenge of being able to recruit and retain Ph.D. faculty in computer science: more than 60 percent of computer scientists with Ph.Ds. or master’s degrees go into industry where the pay is significantly higher.

Computer science capacity challenges in California’s public colleges are a state workforce and economy concern. California currently has nearly 70,000 open computing jobs across the state.

Our workforce needs both more computing talent and more diverse talent in terms of ethnicity and gender — and our low-income students and those who are first in their families to attend college need access to these jobs and the social mobility opportunities they offer.

These challenges are also a state public education pipeline concern. State political and educational policy leaders, as well as public higher education institutional and campus leaders, need to ensure that all students with an interest in studying computer science in college have access to viable pathways to get such an education and be prepared to compete for opportunities in California’s growing tech economy irrespective of their geographical location or socioeconomic status.

Otherwise we run the risk of generating enthusiasm for computer science among our K-12 public school students without expanding the ability of our colleges to admit and graduate more computer science majors — which will only heighten the existing capacity crisis.

•••

Trish Boyd Williams is a former member and computer science lead of the California State Board of Education. Sathya Narayanan is a professor of computer science at California State University Monterey Bay and member of the state board’s computer science strategic implementation plan advisory panel.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

Comments (5)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Dan Jen 2 years ago2 years ago

Getting admitted this year has been extraordinarily difficult. My son applied to computer science programs at 5 UC's and 5 Cal State schools with a 4.2 weighted GPA and was admitted to only one school (the lowest of the low of the CSUs). Completely demoralizing. He's now thinking of taking a year off and reassessing his career path; maybe computer science isn't right for him. It's been tough on him, especially after being … Read More

Getting admitted this year has been extraordinarily difficult. My son applied to computer science programs at 5 UC’s and 5 Cal State schools with a 4.2 weighted GPA and was admitted to only one school (the lowest of the low of the CSUs).

Completely demoralizing. He’s now thinking of taking a year off and reassessing his career path; maybe computer science isn’t right for him. It’s been tough on him, especially after being applauded for his academic success for the past 12 years and getting test scores in the top 1% that aren’t being factored into the admission decision.

SD Parent 4 years ago4 years ago

There is much talk in industry for more CS majors to fill the demand, but as noted, capacity in California's undergraduate programs in CS is the bottleneck for filling that demand. Another factor that wasn't addressed in this piece is that a significant portion of students in undergraduate (and to an even greater extent for graduate) CS programs are not California residents. For example, in 2018, 6% (1,965) of undergraduate students attending a UC … Read More

There is much talk in industry for more CS majors to fill the demand, but as noted, capacity in California’s undergraduate programs in CS is the bottleneck for filling that demand. Another factor that wasn’t addressed in this piece is that a significant portion of students in undergraduate (and to an even greater extent for graduate) CS programs are not California residents. For example, in 2018, 6% (1,965) of undergraduate students attending a UC in any engineering program are from out of state and 13% (4,378) are international students. And the total number of non-resident undergraduate students in these UC engineering programs is higher than the total number of LatinX students (5,901) in these programs. (Statistics specific to CS majors and for CSUs by major are not readily available.)

California’s universities like to admit non-California residents because they pay much higher tuition, which helps with their bottom line. However, if as a state we’re serious about meeting the demand in the CS and want to give opportunities for California students – particularly students of color – to meet this demand, then California’s publicly funded colleges and universities need to expand California students’ access to CS programs by increasing the size of these programs, limiting non-resident enrollment in these programs, or both.

el 4 years ago4 years ago

I think it's really important to build capacity at the university level to accommodate more CS students. In addition, I think the way these departments were built needs to be revamped to be more like the math department, where they not only support their own majors, but students in every department as part of a general education. Some sort of basic programming tools course should probably be available to every major. At its heart, writing a … Read More

I think it’s really important to build capacity at the university level to accommodate more CS students.

In addition, I think the way these departments were built needs to be revamped to be more like the math department, where they not only support their own majors, but students in every department as part of a general education. Some sort of basic programming tools course should probably be available to every major.

At its heart, writing a computer program is just about writing very clear instructions that cover every possible circumstance, that will be interpreted mechanically. (I like to think of it as “will be interpreted as wrongly as possible.”) This skill is essential beyond STEM and deeply into law or any kind of human communication. This is a skill you need to write a good disaster plan or a mission critical checklist. It’s a great leadership skill.

The ability to know that the likely or hopeful or preferred path isn’t the only path, and the ability to find and document the others, is the most important skill I have as a computer professional.

At the moment, these courses aren’t really set up to be accessible, available, or useful to people who don’t plan to be computer technicians or full on computer professionals. The field changes quickly and self-education is a strong part of the landscape, so specific languages or tasks aren’t necessarily what I’m suggesting. We could do a lot to build a base about how to learn about computers, so that it’s easier for our graduates to guide their own next steps.

Replies

Bo Loney 4 years ago4 years ago

Thank you El for your insight on the beneficial leadership skills CS students develop and the many ways they can benefit society beyond programming.

Bo Loney 4 years ago4 years ago

It appears that more room is needed in general for every field of study when even going undeclared is now an impacted program. Gen Z is set to be the most educated in the history of America. It’s time to scoot over and make more room.