Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

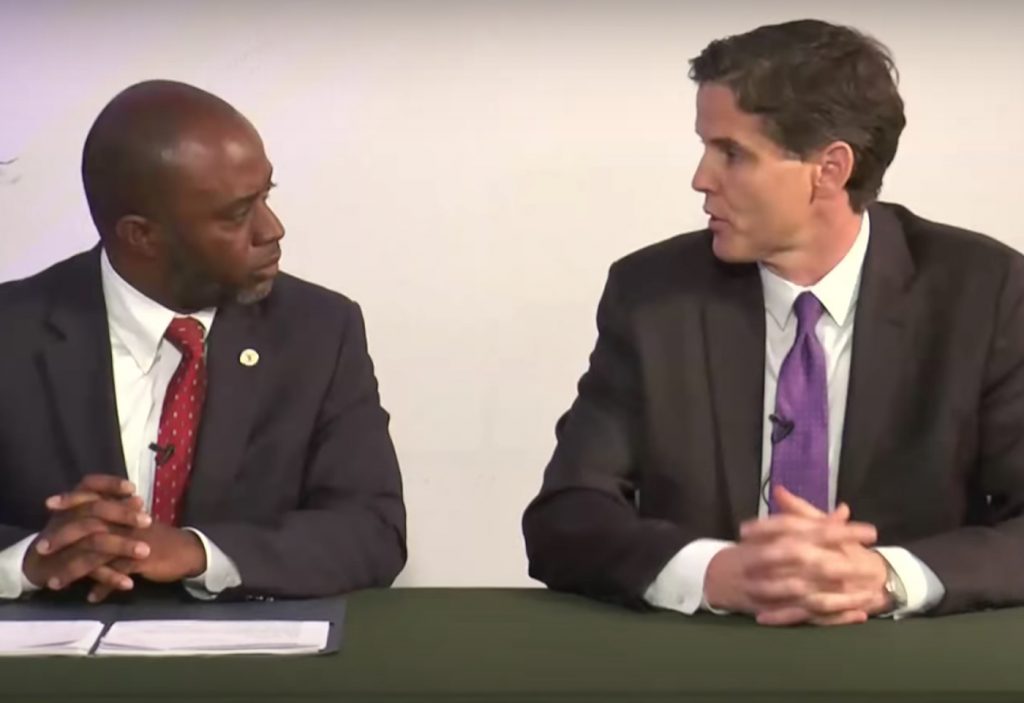

Marshall Tuck and Tony Thurmond will face each other in the November general election for state superintendent of public instruction in what could be a closely contested and very expensive race funded by wealthy individuals who back charter schools and labor unions that want to restrict their growth.

In other words, the race may look a lot like the last one, four years ago, when Tuck, a school reformer who has run charter schools and alternative district schools in Los Angeles, narrowly lost to State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson.

On Tuesday, Tuck edged Thurmond 37.2 percent to 35.6 percent, establishing himself as the front-runner to head up the nation’s largest and most ethnically diverse school system, with 6 million students. Tuck and Thurmond are both Democrats, but the office is nonpartisan — a candidate’s party affiliation is not listed on the ballot — and any candidate who gets 50 percent in the primary is the winner without requiring a runoff election.

But two relatively unknown candidates with no prior political experience prevented that. Steven Ireland and Lily Ploski together captured 27.2 percent of the vote. On Wednesday, Ploski, who finished third with 16.3 percent, endorsed Thurmond, stating in a press release, “I urge my supporters to get behind Tony’s progressive campaign to make California’s public schools the best in the nation.”

Like Torlakson, Thurmond, a second-term assemblyman, has the support of the state Democratic establishment and the state’s two teachers unions. A social worker by training, Thurmond, 49, founded or ran several nonprofit organizations that worked with low-income foster children, truant students and incarcerated children in the Bay Area before turning to politics. He served one term on the city council in Richmond and on the West Contra Costa Unified school board before being elected to the Assembly district serving Richmond, Berkeley and parts of Oakland. He chairs the Assembly Labor and Employment Committee and serves on the Assembly Education Committee.

After a short career in finance, Tuck, 44, has spent most of two decades as a school administrator. For five years he was the first president of the Green Dot Public Schools, a network of charter high schools in low-income neighborhoods of Los Angeles. He then became founding CEO of the nonprofit Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, whose goal was to turn around some of Los Angeles Unified’s schools with the highest dropout rates. For two years after his first run for state superintendent, he was educator in residence at the New Teacher Center, a national nonprofit based in Santa Cruz that works with districts on training and mentoring teachers and principals.

As administrator of the 2,500-employee California Department of Education, the state superintendent lacks the authority to set education policy. But the superintendent can influence it as the top elected official responsible for K-12 schools.

Tuck and Thurmond largely agree on some of the critical issues facing California’s schools: the need to substantially increase funding, address a teacher shortage, fund preschool for all children and raise achievement of low-income students.

But in interviews on Tuesday night, Thurmond and Tuck emphasized distinctions between them. Thurmond emphasized, “I am a progressive Democrat, and we will galvanize our base.” Alluding to Tuck, also a registered Democrat, Thurmond said, “I am not trying to cultivate Republican votes.”

Tuck said he is the candidate for “real change” and that he is not a “career politician,” alluding to Thurmond’s service as an elected official in Richmond and now in Sacramento. “I have done the work turning around low-performing schools.”

Tuck’s campaign has raised about $3 million and Thurmond’s campaign about $2 million. But in coming months, they may find their voices drowned out by the polarizing messages of the independent expenditure committees that endorse them and may be ready to spend millions more.

“Thurmond’s supporters will try to paint Tuck as a Trump conservative. Tuck’s strategy will be to run against the status quo and the perceived failures of the education establishment,” said Kevin Gordon, president of Capitol Advisors Group, an education consulting company based in Sacramento. “The trick will be for each to define the other guy before they can define themselves.”

As longtime political observer Dan Schnur, former director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at USC, put it, “Will Tuck be defined as a friend of Arne Duncan,” President Obama’s secretary of education, who has endorsed Tuck, “or will he be seen as a friend of Betsy DeVos?,” Trump’s education secretary whom Tuck has sharply criticized.

Unions, led by the California Teachers Association, have donated about $3 million to an independent expenditure committee backing Thurmond.

Wealthy charter school promoters, including Los Angeles philanthropist Eli Broad, have already given $7 million to an independent committee supporting Tuck.*

Several of the same donors also gave heavily to independent committees supporting the gubernatorial campaign of former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. They viewed him as the candidate most likely to protect charter schools, as Gov. Jerry Brown has done for the past eight years.

But Newsom and second-place finisher John Cox, a Republican, trounced Villaraigosa on Tuesday. With Villaraigosa’s defeat, unions and charter school backers may shift dollars to the state superintendent’s race. That also happened in 2014, when Brown faced novice Republican challenger Neel Kashkari and the Tuck-Torlakson race became a proxy war over charter schools.

Other than to administer federal startup grants for charter schools, the next state superintendent will have little direct role in charter approvals or renewals. But the CTA and the California School Boards Association are expected to capitalize on Brown’s departure to try to impose restrictions on charter school expansion that could determine their future after two decades of rapid growth.

Tuck and Thurmond both say they oppose for-profit charter schools and would close those that are consistently low-performing. But they differ on important details. Tuck opposes a charter moratorium, while Thurmond favors a “pause.” Tuck opposes enabling school boards to reject a charter application based on a potential negative financial impact on their districts. Thurmond would condition approval on compensating a district for loss of revenue, a potentially expensive alternative.

Both Tuck and Thurmond said Tuesday that charter schools should not be the defining issue in the race.

“I have been to dozens of events, and charters have not been a big part of our conversation,” Tuck said. “People want to know why funding is so low, why there is a teacher shortage and why students aren’t performing at grade level.”

As a school board member, Thurmond said, he approved and reauthorized charter schools and built a high school housing both a charter school and a traditional public school. “As superintendent I would serve every single student in the state, whether they attend a charter school or a district school,” he said.

Both also said they anticipate more negative ads in the months ahead.

“Those billionaires who spent that money against me don’t know me and want to put me into a box,” Thurmond said. “It’s a false narrative.”

“I can’t prevent people from telling lies,” Tuck said, referring to ads tying him to Trump and DeVos. “They’re bad for politics and distractions from stepping up and supporting our schools. I want to change the status quo.”

* Correction: An earlier version incorrectly stated that Netflix CEO Reed Hastings and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg have given to the independent expenditure committee supporting Marshall Tuck. At this point, they have given only the maximum personal contribution of $14,600 directly to Tuck’s campaign.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments (10)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

J 5 years ago5 years ago

In my opinion, neither of these gentlemen are suitable for the office, because neither of them has ever indicated what they intend to do to solve the real issue. For that matter, the majority of the electorate is not qualified even to vote regarding this issue. Why? Because the public at large has repeatedly backed legal and legislative measures which have reduced the responsibility of the individuals which benefit from education the most; the children … Read More

In my opinion, neither of these gentlemen are suitable for the office, because neither of them has ever indicated what they intend to do to solve the real issue.

For that matter, the majority of the electorate is not qualified even to vote regarding this issue. Why? Because the public at large has repeatedly backed legal and legislative measures which have reduced the responsibility of the individuals which benefit from education the most; the children and their parents.

Our form of testing students does not hold students accountable. Our budgeting process for education, relying on gambling proceeds and emergency revenue measures, makes it clear that the electorate and our elected representatives, would rather build prisions than schools, and views the entire process as “someone else’s responsibility.”

The essence of democracy is personal responsibility, but we live in an age where no one wants to be held responsible. How very corporate of us. Until this changes, public education cannot improve.

Donald L Macleay 6 years ago6 years ago

It is telling that the links to some description of the other two candidates was only provided after a comment complaining them. You had time for words to describe how obscure they are, but not who they are. For that we have to go through the maze of this website without being told that there is even anything to find. The idea that if you don't have a money trail and can't find … Read More

It is telling that the links to some description of the other two candidates was only provided after a comment complaining them. You had time for words to describe how obscure they are, but not who they are. For that we have to go through the maze of this website without being told that there is even anything to find.

The idea that if you don’t have a money trail and can’t find a bio on the website, that justifies not knowing much seems to be what is implied in the answer.

You call this quality journalism?

It isn’t even efficient report writing.

Robert D. Skeels, J.D. 6 years ago6 years ago

Much respect to the distinguished Dr. Lily Ploski for running for State Superintendent of Public Instruction (SSPI), and subsequently endorsing Tony Thurmond. We must unite against Thurmond’s right-wing opponent, who’s a Betsy DeVos, Tom Horne, and John Huppenthal acolyte.

Anonymous 6 years ago6 years ago

Thurmond did nothing as a trustee on the West Contra Costa Unified School District board of education. His one term was merely a stepping stone to his campaign for the state Assembly. He has the support of the Democratic machine but doesn’t have much of a track record.

Frances O'Neill Zimmerman 6 years ago6 years ago

Funny about the candidacies of two unknowns in this important race for Superintendent of Public Instruction whose “spoiler” influence have forced a run-off in November between reformer Marshall Tuck and union-backed Tony Thurmond. It would be helpful if voters could learn here who Steven Ireland and Lily Ploski are and who backed them.

Replies

John Fensterwald 6 years ago6 years ago

Frances:

We did write about Lily Ploski, as an introduction to her candidacy here and covered her appearance at a forum at USC here.

Steven Ireland’s campaign website, which does not include a bio, can be found here.

Neither candidate filed a report of donations or expenditures with the Secretary of State.

John Fensterwald 6 years ago6 years ago

Frances:

We did write about Lily Ploski, as an introduction to her candidacy here and covered her appearance at a forum at USC here. Her website is here.

Steven Ireland’s campaign website, which does not include a bio, can be found here.

Neither candidate filed a report of donations or expenditures with the Secretary of State.

Today, Lily Ploski threw her support behindTony Thurmond.

John Fensterwald 6 years ago6 years ago

Frances:

We did write about Lily Ploski, as an introduction to her candidacy here and covered her appearance at a forum at USC here. Her website is here.

Steven Ireland’s campaign website, which does not include a bio, can be found here.

Neither candidate filed a report of donations or expenditures with the Secretary of State.

Today, Lily Ploski threw her support behind Tony Thurmond, which I note in an update to the story.

Joe Filoso 6 years ago6 years ago

I totally agree with you, Frances. I’ve done research on Lily, and she represents what many students have gone through during their academic endeavors. She has been through it, the storms of life. You have to look into her for yourself. Honestly, I just learned of Ms. Ploski this past week. The media and the governor wanted this state superintendent race to be a 2 candidate race from the very beginning.

mr isaac 6 years ago6 years ago

If Tuck sips from DeVos' devil's spoon, he can't complain when accused of bad breath. He is a charter school advocate. If Thurmond's lets his strings be pulled by the teacher union, he cannot escape being called a labor puppet. He is a charter school opponent. I can see no "lies" about Tuck or "false narratives" about Thurmond. Just look at the money. This is an up or down vote … Read More

If Tuck sips from DeVos’ devil’s spoon, he can’t complain when accused of bad breath. He is a charter school advocate. If Thurmond’s lets his strings be pulled by the teacher union, he cannot escape being called a labor puppet. He is a charter school opponent. I can see no “lies” about Tuck or “false narratives” about Thurmond. Just look at the money. This is an up or down vote on charter expansion. I wish the candidates would run on the charter issue, because that is how people are voting.