Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposal to link over $3 billion in funding for California’s community colleges to the number of low-income students they enroll and to student outcomes in general is coming under increasing scrutiny — and is likely to face more in the coming months.

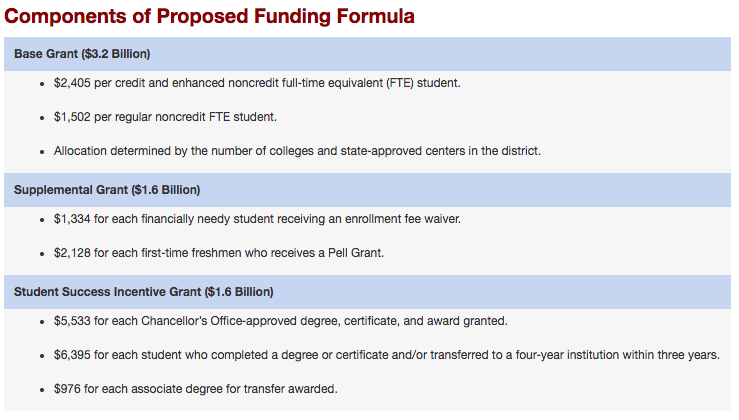

Currently California’s community colleges receive nearly all of what are called “general-purpose” funds — $6.2 billion in 2017-18 — based on the number of enrolled students. The governor’s plan would instead make just half of those dollars depend on student enrollment. A quarter would fund colleges based on the number of degrees or certificates students earn or who are ready to transfer. Another 25 percent would be tied to the number of students receiving certain kinds of financial aid.

While largely endorsing Brown’s new funding formula, the Legislative Analyst’s Office is recommending that Brown tie more of these funds to the academic outcomes of low-income students as an incentive to ensure they succeed, something his proposal currently does not do.

Assemblyman Jose Medina, D-Riverside, chair of the Assembly Higher Education Committee, said he plans to hold a committee hearing about the proposal “so that we can look at it with more detail.” He said the proposal is worrying some community college leaders because of the uncertain impact it would have on the funding they receive. “This is a big change,” Medina said.

He also worried about Brown making his funding proposal part of the budget process rather than going through the normal legislative process. “By just putting it in the budget,” he said Brown is “circumventing the Legislature being able to fully discuss his ideas.”

What might influence how Brown’s proposal will be received in the Legislature is the experience of more than 30 other states that have some version of what Brown is proposing — what are called “performance-based” or “outcome-based” funding plans for their public colleges and universities.

Most apply these plans to both their community colleges and four-year public universities. If Brown’s proposal gets approved by the Legislature, California would join five other states that apply this funding approach only to their community colleges. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, the others are New York, North Carolina, Texas, Washington State and Wyoming.

Brown’s plan, included in his proposed budget that he issued in January, targets about $6 billion that California’s 114 community colleges receive out of their total budget of about $15 billion.

Currently they receive these general purpose funds based almost solely on the number of students they enroll. Brown wants to allocate those funds in the following ways, according to the accompanying “trailer bill” released Feb. 1:

The LAO is recommending that more money in this last category be sent to colleges where low-income students are showing positive outcomes. “We will take their suggestions under consideration,” said H.D. Palmer, spokesman for the California Department of Finance, referring to the LAO’s recommendations.

Brown has also included what is called a “hold-harmless” provision for 2018-19 that would prevent any college district from receiving less apportionment funding than it did in 2017-18. In 2019-20 and after, districts would receive at least the per-student funding they would have received in 2017-18.

One key condition of the proposed formula is that all districts adopt the Vision for Success document the California Community Colleges Board of Governors approved last summer. That document set aspirational goals for degree completion and wage gains for career technical education students.

While different in some important respects, the plan bears similarities to Brown’s landmark Local Control Funding Formula for K-12 schools. That formula targets additional funds for school districts based on the number of low-income and other high-needs students they serve. But unlike the K-12 funding formula, Brown’s community college plan would also fund colleges based on several measures of student performance.

Some researchers of performance-based funding plans in other states say that there is a danger that linking funding to student academic performance could unfairly reward schools that have more students who come from more affluent households and are more likely to graduate anyway — and penalizes colleges that serve needier populations. There’s a risk of “favoring colleges that already are doing well on those metrics,” said Nicholas Hillman, a professor of higher education policy at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In 2015, the National Conference of State Legislatures recommended that any funding plan based on student performance focus also on students with greater economic needs. The organization advised states to “include a measure to reward colleges that graduate low-income, minority” and older students.

Brown’s proposed funding formula attempts to address this concern. As his administration explained in its January budget proposal, the formula is intended to “encourage access for underrepresented students, provides additional funding in recognition of the need to provide additional support for low-income students and rewards colleges’ progress on improving student success metrics.”

While some states have linked funding to student outcomes in some form since the 1990s, the practice really took off after 2008 as states wanted to maximize the impact of their funding during the Great Recession.

The concept of linking funding to student performance is not entirely new in California. Beginning in the late 1990s, the Legislature initiated a program called Partnership for Excellence, which provided supplementary funds — up to $300 million in its final year — in exchange for community colleges promising to improve student outcomes on an array of measures. But the program was never fully implemented, and in 2005 for a range of reasons it was scrapped altogether.

Amy Li, a professor of higher education at Northern Colorado University in Greeley, said that states using outcomes-based funding models are in effect telling colleges “if we give you money for this particular goal then you as an organization should do whatever you need to do … to produce the outcomes that are important to the state.”

Performance-based funding models across the country vary considerably. In Tennessee, colleges and universities receive 85 percent of their state money based on student outcomes. In some respects, the state’s approach is similar to Brown’s, though there are differences: Tennessee’s community colleges are also judged on the extent to which students find jobs after they graduate.

Texas began using a funding formula tied to outcomes in 2014-15. It bases roughly 10 percent — or $180 million — of state money for community colleges (excluding faculty benefits) on how well students do. The formula assigns districts points for various student milestones, such as completing remedial education classes, earning a degree or transferring to a four- year college. Each point brings an extra $172 per student to the college.

Whether the formula has spurred improvement in his state is “the million-dollar question,” said Dustin Meador, who heads government relations at the Texas Association of Community Colleges, representing the state’s 50 community colleges. The association supported the formula.

There is some evidence that Texas colleges are responding positively to the new formula. For example, colleges have earned points for improvement at a faster rate than their enrollment has grown, Meador said. Colleges, he added, have been simplifying students’ academic roadmaps that they must follow to earn a degree or transfer, which may explain some of the improvement.

In some cases, colleges that lost funding because of declines in enrollment were able to maintain their funding levels anyway because of the extra money they received based on improved student outcomes.

Researchers of performance-based funding also point to evidence that the performance-based formulas can spur community colleges to graduate more students with certificates that take a shorter time for students to earn, such as those in auto mechanics, biotechnology or landscape design, than students earning associate degrees. Those take a minimum of two years to earn.

In his analysis of performance-based funding formulas in place for community colleges in Ohio, Tennessee and Washington State, Hillman found that on average the number of certificates and other credentials earned by students went up, while the number of associate degrees stayed flat on average. Hillman thinks that’s because it’s easier to produce more degrees “when they can be done in a relatively short amount of time.”

Others say the results are more mixed. In some states with performance-based funding formulas for community colleges, students have earned more associate degrees, while in others they have earned fewer.

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Stephen Blum 6 years ago6 years ago

Thoughts on New and “Improved” Community College Funding Formula Proposal In 1978, California voters passed Proposition 13 with the goal of reducing property taxes. Proposition 13 did successfully bring down California’s property tax rates, but the measure also had unintended consequences. Before Prop. 13, local school districts held taxing authority. For better or worse, Proposition 13 transferred responsibility for setting tax rates and decision-making regarding tax dollar distribution into the state government’s hands. Understandably, since the state … Read More

Thoughts on New and “Improved” Community College Funding Formula Proposal

In 1978, California voters passed Proposition 13 with the goal of reducing property taxes. Proposition 13 did successfully bring down California’s property tax rates, but the measure also had unintended consequences. Before Prop. 13, local school districts held taxing authority. For better or worse, Proposition 13 transferred responsibility for setting tax rates and decision-making regarding tax dollar distribution into the state government’s hands.

Understandably, since the state government took on the responsibility of handing out educational dollars, it has created rules regarding how the funding should be spent. The California Legislature and the governor have created one categorical program after another instructing K-12 school districts and community colleges on how to spend state-allotted money. Some programs have been good, some not so good, and some have been neutral, depending upon whom one asks. Many of these “ideas” are short-lived and fall to the wayside as politicians are replaced by new people with “better” ideas on how to improve education. In education, like baseball, everyone believes they are an expert.

The latest idea for funding community colleges is the “Performance Funding Formula.” Under this plan, community colleges would move from enrollment-based funding to a formula based 50 percent on enrollment, 25 percent on the number of enrolled low-income students, and 25 percent on the number of degrees and certificates granted, the number of students who complete a degree or certificate in three years or less, and per associate degree or transfer granted. During this plan’s first year of implementation, the state would hold districts harmless to the level of funding received in 2017-18.

California has seen other ideas on how to rearrange the school funding deck chairs. This one does not seem very wise. We have yet to see any substantial data, to support the proposition that changing the funding formula would bring about the desired changes as outlined in the Vision for Success, which was approved by the California Community College Board of Governors in fall 2017. Apparently, the plan is based solely on the authors’ hunches, instincts, and/or acumen. The Department of Finance recently ran a proposal outcome simulation. It predictably showed some community college districts would be “winners,” receiving as much as 18 percent more funding, while some would lose as much as 14 percent of their funding, and still others would see little to no change.

Like many new ideas, performance funding is being rushed to reality. A small task force of college CEO’s was quickly created and asked to formulate recommendations within just a few months. The new funding formula is on schedule to be passed this summer and embedded after just one “hold harmless” year. We don’t yet know the true repercussions of this dramatic funding formula revision. At this point, we can merely speculate at the pluses and minuses it will bring. It is unwise and imprudent to rush into such a substantial shift without careful study of whether it can achieve the desired results, as well as what unintended consequences might arise.

The most perplexing part of this proposal is that it was formed as part of Governor Brown’s initial budget proposal last January. To his credit, Governor Brown has proven to be a careful, prudent, and calculated guardian of the state budget. Yet, this sweeping proposal seems out of character for him. It casts caution and wisdom aside on the hope that this new funding formula will cause institutions to suddenly become “more successful.”

Education is multifaceted and complicated. Improving educational outcomes is not as simple as allocating more or less money. Those who came up with this idea did not think it through and should take the time to allow scrutiny and thorough stakeholder debate before rushing it through.

Serving approximately 2.1 million students, the California Community Colleges form the largest college system in the world. Far too many people count on California Community Colleges to make changes of this magnitude without a thorough investigation to ensure the plan will result in the desired outcomes.

Stephen P. Blum, Esq.

Ventura County Community College District Trustee

Replies

Dina Pielaet 6 years ago6 years ago

Very well stated Trustee Blum. I feel that Amy Li (article above), who stated that outcomes-based funding models are in effect telling colleges “if we give you money for this particular goal then you as an organization should do whatever you need to do … to produce the outcomes that are important to the state.” is a an accurate assesment. Needless to say, I do feel this plan may have the potential for confusion in … Read More

Very well stated Trustee Blum. I feel that Amy Li (article above), who stated that outcomes-based funding models are in effect telling colleges “if we give you money for this particular goal then you as an organization should do whatever you need to do … to produce the outcomes that are important to the state.” is a an accurate assesment. Needless to say, I do feel this plan may have the potential for confusion in predicting a Community College District’s year-to-year budget, while creating an enormous additional load of accountability on already overworked staff. I do feel that every college system should be accountable to each and every student to the best of their abilities. But I agree with you in that this vast swing of the fiscal pendulum needs much discussion, forecasting and review. Thank you for your service to to the California College District!