Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

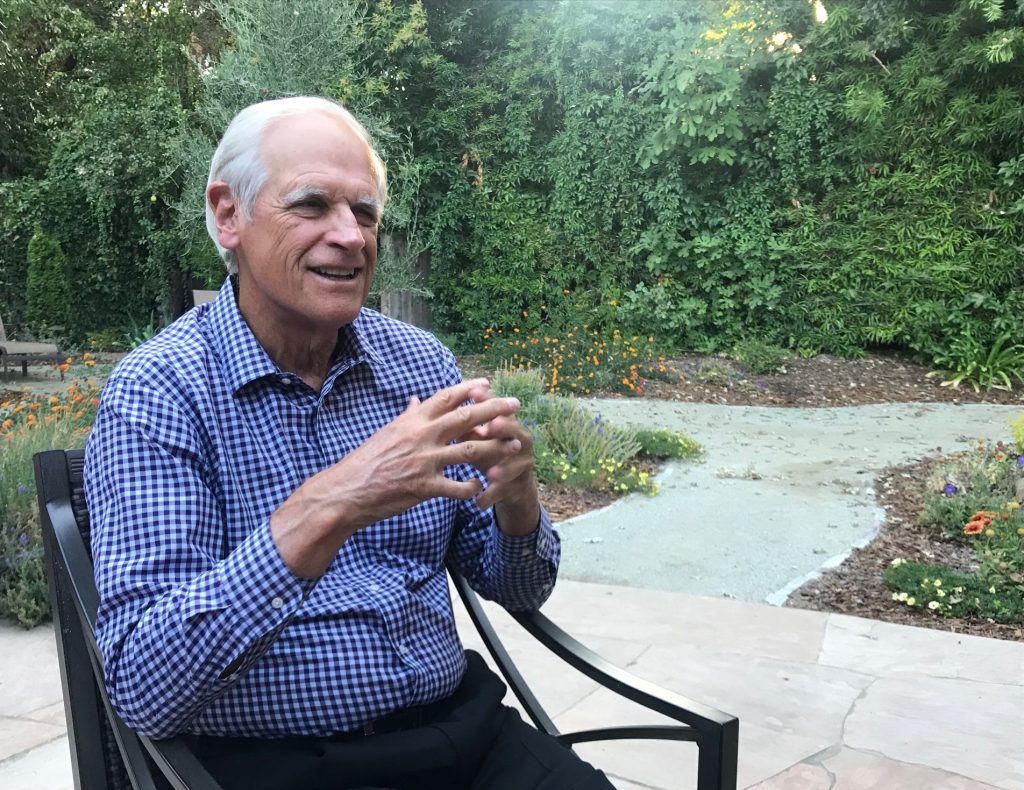

What does the “father” of California’s quarter-century old charter school law think of it now? EdSource recently caught up with former State Sen. Gary Hart, a Democrat who represented Santa Barbara in the Assembly and Senate for 20 years before retiring in 1994. In 1992, as chairman of the Senate Education Committee, he authored the nation’s second charter school law. Sue Burr, a consultant to the committee at the time and currently a member of the State Board of Education, played a major role in drafting it. EdSource writer John Fensterwald asked Hart in an interview and in writing what he was trying to do then and how, in hindsight, he might write a different law today. The answers have been edited for length and clarity.

The original law capped the number of charter schools statewide at 100, with no more than 10 in any one district and 20 in Los Angeles Unified. In 1998, the Legislature raised the limit to 250 charter schools plus an additional 100 more each year after that.

EDSOURCE: Is it as you envisioned, that we would have more than 1,200 charter schools in California?

HART: No. It’s always hard to predict how legislation is going to play out. Although it was very contentious, I didn’t view it as something that was going to be earth-shaking or have the magnitude that it has.

The original law called for up to 100 charter schools. That was changed a number of years later. When the law first passed, we had no idea as to whether there would be any charters. It was like you give a party and you don’t know if anyone will come or not. It was kind of slow in the beginning. The accelerated growth has been just extraordinary, and it’s not something that not only myself, but I don’t think anybody else could have predicted or even imagined.

EDSOURCE: So what do you attribute that growth to? Are the charter schools from what you can tell doing collectively or individually what you would have hoped?

HART: It’s really hard to generalize because charters vary so much. Generally speaking, I’m supportive. With any legislation of this magnitude, there are always going to be issues and concerns. I do think there has been such a focus on how many new charters, it’s focusing on quantity and I had hoped initially there would be a lot more focus on quality, a more careful review of charters.

EDSOURCE: One of the questions originally was whether charters should be seen as a way to innovate and set examples for other district schools to learn from or to give parents a choice in high-poverty neighborhoods where they are dissatisfied with their schools. Those are really two different focuses.

HART: I think it was both. First and foremost was innovation and reform, giving an opportunity for people to do things differently and not be constrained by all of the rules and regulations from the district, from collective bargaining.

I heard over and over again from school folks, “Stop passing all these laws. We’re spending all of our time being compliance officers and bureaucrats and we’re not able to do our jobs as educators.” I thought that there was some truth to that and so passing this law really gave an opportunity for educators to be educators and not be as concerned about rules and regulations.

After the law was passed, there wasn’t much that came forward either from teachers or administrators or school board members who had complained bitterly about state laws. Instead of going out and doing it, a lot of people resisted. That’s not to say they were wrong because going through the whole process can be quite time-consuming and there’s a lot of blood on the floor sometimes for establishing these things.

This other aspect was also important — the people who felt that the existing schools, particularly in low-income areas, were not serving their needs; their school districts were too large or dysfunctional. They needed to have something that would be their own.

One of the concerns was, “This charter law will be for sophisticated parents who have a lot of time on their hands.” It was somewhat of a surprise to see that places like LA Unified and Oakland and other large urban school districts were where the charters were taking off. I think there was a dissatisfaction on the part of parents, but also because the business community and the foundation community got behind these efforts and provided resources. I never anticipated that charter management organizations would have such an important role.

EDSOURCE: The financial impact on a district was not part of the law. Was it brought up at the time?

HART: I don’t think so. The law didn’t have large-scale financial ramifications. We were talking about 100 charters statewide.

The bill was a major effort to try to defeat the voucher proposal that was going to be on the ballot and we saw it as an alternative to vouchers that would not go down that path of providing the large taxpayer subsidies to private schools and violating the church-state separation right. (Editor’s note: Prop. 174, which would have given parents a tuition subsidy to a private or parochial school equal to half of per-student funding at public schools eventually did make the November 1993 general election ballot; voters defeated it 70 to 30 percent.)

There was strong teacher opposition to the charter legislation from both AFT (American Federation of Teachers) and CTA (California Teachers Association) even though ironically, I got the idea from Al Shanker (the late president of the American Federation of Teachers) who had written about it. I was a great fan and Shanker had come out and testified on a number of occasions to legislation that we were considering.

“Charter fights in places like L.A. Unified have become almost religious wars, where large amounts of money are spent, and having an appeals process that is less political makes sense to me.”

The focal point of the unions was largely to ensure that collective bargaining laws would not be tampered with in the charter law. That issue was very contentious and I refused to budge. My position was that there needed to be a choice for teachers whether to form a union at a charter school.

EDSOURCE: How did you ever get it passed?

HART: It wasn’t easy. The unions were strongly opposed and many other education groups — ACSA (Association of California School Administrators) and CSBA (California School Boards Association) — were neutral perhaps because they didn’t want to antagonize CTA. It was pretty lonely out there. We engaged in some legislative jiu-jitsu and pulled the bill out of conference committee and passed it quickly off the Senate floor with no debate and sent it to Gov. Wilson, who signed it into law. If we had followed traditional procedures and the unions had had time to work the bill, it likely would not have passed.

EDSOURCE: Did it become apparent that there would be resistance and that some folks in many districts at the time didn’t like competition? You knew that, right, because you set up an appeals process?

HART: We did, and it wasn’t that we had a cynical view towards school districts, but there was a potential conflict of interest that made, I thought, an appeals process a good idea. School boards and school administrators might oppose any charter because it might mean less district control, less revenue and more competition. So having an appeals process made sense and I thought county boards, who were also elected and had a sense of local issues, were the right bodies to hear appeals. Six years later the charter law was amended to provide another appeal to the State Board of Education. I understand now the state board spends up to half its time hearing charter appeals, which I’m not sure is a good use of state board time given all the other policy matters on their plate.

EDSOURCE: Would you eliminate that ultimate appeals process because it’s not a good use of (state board) time, or do you think someone else ought to be the ultimate authority or should you just keep it at the county level and whatever happens there happens?

HART: I still believe a charter appeals process is a good idea but charters are now becoming a campaign issue with some county boards of education so I’m not sure they are the right venue for appeals. Charter fights in places like L.A. Unified have become almost religious wars, where large amounts of money are spent, and having an appeals process that is less political makes sense to me. Perhaps the State Board of Education could appoint an expert panel to review and have the final say on charter appeals. I favor making the process less political and handled by more neutral people.

EDSOURCE: Some districts are very frank about the financial impact of charter schools. “Look, we can’t afford it. We’re making cuts and you’re asking us to start new charter schools adding to the financial problems we have.” If you were to redo the law, would you hold a district harmless for the financial impact or compensate it for the impact of a charter?

HART: Some districts face loss of revenue due to charter growth, and many districts face unsustainable long-term employee health care costs and all districts face escalating pension contributions. A review of state financing seems in order. We have had funding adjustments to mitigate for declining enrollment. Perhaps something like that ought to be considered for districts with many charter schools. But a strict “hold harmless” for districts losing students to charters doesn’t make sense, as it would reward districts for not being competitive and it might also provide an incentive for districts to push out “undesirable” students. Trying to accommodate various factors that are affecting the financing of a district gets very complicated. There are unintended consequences you have to be careful about.

Districts have many financial challenges and it seems to me that charters are not the primary or even significant part of the financial problems districts face in the long term — those problems are going to remain with or without charter schools.

EDSOURCE: Looking back, seeing what people are saying now are some of the challenges to the law, what changes might you make?

HART: We now have more than 1,000 charter schools in California and we know little about their successes and failures. Some work has been done comparing charter to traditional public schools on student achievement but, given the great variety of charter schools, I’m not sure about the value of that body of research.

I would be interested in research on topics like school size — charters tend to be smaller. School mission — charters tend to have a specific rather than a comprehensive mission. Accountability — it’s easier to dismiss staff in charter schools. And school governance — charter board members are not elected by the general public and do not have to raise money to run for office. There’s a lot to explore with 25-plus years of experience and data.

I think we’re hungry for highlighting and replicating what is working well, whether it’s in a charter school or in a traditional school. We don’t do a good job of that.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

Comments (9)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Mary Ellen 6 years ago6 years ago

One of my criticisms of the charter enterprises (including the nonprofits) is their deceptive marketing. Low income parents are led to believe that their children will be graduating from Ivy League universities. How many graduates of charter schools finish college within four to six years? And how does that compare to the college graduation rate of public school students?

Gisele Huff 6 years ago6 years ago

If Gary Hart is positing that his last paragraph depends on his penultimate one, then he is mistaken. The idea that gathering information about charter schools that doesn't include student performance is problematic. After all, it is (or emphatically should be) about the children. Finding out what actuates the various models and then, hoping that leads to replication has been proven to be the most elusive element of this reform for the … Read More

If Gary Hart is positing that his last paragraph depends on his penultimate one, then he is mistaken. The idea that gathering information about charter schools that doesn’t include student performance is problematic. After all, it is (or emphatically should be) about the children. Finding out what actuates the various models and then, hoping that leads to replication has been proven to be the most elusive element of this reform for the last 25 years.

Case in point: KIPP was founded 25 years ago. It is significantly funded by philanthropic dollars. It has 224 schools that serve 96,000 students. Do the math. How many years would it take to replicate this successful model to affect the 48 million children who go to traditional public schools every day?

Reforming the governance of schools as Hart describes doesn’t go to the core of the problem. We have an antiquated, fatally flawed Industrial Age school system that was excoriated in the 1983 report A Nation at Risk. If we don’t fundamentally transform it, we will still be wringing our hands 35 years from now.

SharonSF 6 years ago6 years ago

Wow, this is clearly a sensitive topic. As an uninformed newcomer (and therefore neutral), I yearn for actual data. @John/Hart - Thank you for (re-)starting the conversation. It sounds like money scarcity and power grabs are fueling the passionate disagreements. If there were some relief in these areas, I imagine most reasonable people could and would focus on the content: what's working and what's not (and would be demanding this research). As it is, I … Read More

Wow, this is clearly a sensitive topic. As an uninformed newcomer (and therefore neutral), I yearn for actual data. @John/Hart – Thank you for (re-)starting the conversation.

It sounds like money scarcity and power grabs are fueling the passionate disagreements. If there were some relief in these areas, I imagine most reasonable people could and would focus on the content: what’s working and what’s not (and would be demanding this research). As it is, I can see how most reasonable people, especially in certain districts, would passionately take sides. Parents just want what’s best for their kids.

It’s such a worthy topic, finding educational solutions that are meaningful and fair for all kids. I’m seeing that common goal in this article and in the comments. I hope as a society we can work through the current messiness–our kids deserve that much from us.

Replies

CarolineSF 6 years ago6 years ago

All parents want what’s best for their kids. But charter schools drain resources from public schools, so are parents who want to send their kids to charter schools willing to hurt other kids — and hurt the most vulnerable kids the most — to get what they want for their kids? That’s the eternal quandary charter schools create, and the question that charter advocates try to squelch and drown out.

Lucia Garcia 6 years ago6 years ago

The harm this man's legacy is a tragic set back for educacional equality for brown children in East Los Angeles. We have a charter saturation, they parachute in many of our public schools, or pop up in corner stores, church basements, and empty strip malls. The funding has impacted all public schools tremendously, tax money going to unregulated charters. Yet the public school gets all the "troubled" and spec ed kids back after … Read More

The harm this man’s legacy is a tragic set back for educacional equality for brown children in East Los Angeles. We have a charter saturation, they parachute in many of our public schools, or pop up in corner stores, church basements, and empty strip malls. The funding has impacted all public schools tremendously, tax money going to unregulated charters. Yet the public school gets all the “troubled” and spec ed kids back after norm day. Come see Boyle Heights, where we have a war in every few blocks. It is disgusting what they have done to my community. Jose Huizar, Monica Garcia have sold out my community.

Jim Mordecai 6 years ago6 years ago

The author of California's charter law lacked imagination because his vision was 100 not over 1,000 charter schools. Seems like a way to not take responsibility for what one person calls the Wild West of California charter schools and wash his hands of the harm he has done to public education with "choice" replacing regulation. Also, he seems to still be committed to "competition" as the way to reform public education, a competition between public … Read More

The author of California’s charter law lacked imagination because his vision was 100 not over 1,000 charter schools. Seems like a way to not take responsibility for what one person calls the Wild West of California charter schools and wash his hands of the harm he has done to public education with “choice” replacing regulation.

Also, he seems to still be committed to “competition” as the way to reform public education, a competition between public schools and privately managed charter schools.

But, competition between public and private system didn’t reform the public schools after 25 years, what it did was reduce the pie of education dollars available to public schools. And, competition with the charter school side not having to follow most of the Education Code meant competition was unequal competition.

GrorgeHuff 6 years ago6 years ago

Nice interview, but one clarification and two requests. Clarification- The Board members of the L.A. County Board of Education are appointees of the county Supervisors, not elected. 2. Please ask Gary Hart to reflect upon why basic fiscal and ethical transparency/accountability for charter schools was committed originally - public records act, conflict of interest, open meetings. To what does he attribute the inability to enact them now, after numerous legislative attempts? 3. What … Read More

Nice interview, but one clarification and two requests.

Clarification- The Board members of the L.A. County Board of Education are appointees of the county Supervisors, not elected.

2. Please ask Gary Hart to reflect upon why basic fiscal and ethical transparency/accountability for charter schools was committed originally – public records act, conflict of interest, open meetings. To what does he attribute the inability to enact them now, after numerous legislative attempts?

3. What is Gary Hart’s understanding of why businesses and foundations brought about the proliferation of charter schools? Were they motivated by education-fervor or by an epiphany of very lucrative, opaque financial investments?

CarolineSF 6 years ago6 years ago

I applaud this interview, because I think the press should do a lot more revisiting as opposed to quick-hit coverage and then moving on. I would question whether Hart has actually paid close attention to the impact of charter schools on public schools, though. Doing that probably would not be pleasant for him (though he was catching a wave, and someone else would have sponsored the law if he hadn't). See link below to a … Read More

I applaud this interview, because I think the press should do a lot more revisiting as opposed to quick-hit coverage and then moving on.

I would question whether Hart has actually paid close attention to the impact of charter schools on public schools, though. Doing that probably would not be pleasant for him (though he was catching a wave, and someone else would have sponsored the law if he hadn’t). See link below to a basic lesson on charter schools’ impact.

I’d like to see more revisiting! How about talking to all the forces that in the early ’00s were hailing Edison Schools (a for-profit “education management organization”/charter operator with its stock publicly traded on the NASDAQ) as the miracle that would save public education by applying the efficiencies of the private sector, while making a profit and paying dividends to the shareholders? (At the time, I recall, Gary Hart said that when he sponsored that law, he’d never envisioned for-profit charter schools.) Instead of owning up to when a disruptive innovation was a failure, we tend to move on and pretend it never happened. How can we learn from experience if we do that?

Here are some basics on charter schools for Gary Hart to read. https://teachingmalinche.com/2018/04/29/whats-wrong-with-charter-schools-the-picture-in-california/

Bill Younglove 6 years ago6 years ago

Gary, et al.,

You simply overlook, conveniently it would seem, the essence of both the (first) MN and CA charter school laws. Please share with all of us just exactly where, when, and what kinds of proven teaching strategies developed in the Charter Schools have been replicated back in those public schools they left behind.