Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Andrew and Ariya Boone got the call from Paradise Elementary at 9:30 a.m. on Nov. 8. Fire was roaring toward the town of Paradise and they had to come immediately to pick up their three boys.

Andrew raced to the school as Ariya frantically packed the family’s most treasured belongings and soothed their small daughter while the sky, which had been relatively clear just an hour before, turned so dark that it felt like “10 o’clock at night at 9:30 in the morning.”

“It was insane…the fire was being driven by winds that were so strong it was throwing embers the size of large rocks,” Ariya said Wednesday, recalling the family’s harrowing flight from their home of eight years to an evacuation center at the Yuba-Sutter Fairgrounds in Yuba City.

The Boone children were among at least 3,800 of the more than 4,200 Paradise Unified School District students who lost their homes in the Camp Fire — the deadliest wildfire in California history. Scores of teachers and several school board members were also left homeless, according to officials with the Butte County Office of Education.

A full damage assessment is still underway, but state and county officials confirmed that Paradise Elementary was destroyed and seven other Paradise Unified school sites were either damaged or destroyed. It also leveled nearly 9,000 homes in the town of 27,000 residents. As of Friday morning, 63 people were confirmed dead and more than 600 were still missing, according to multiple reports.

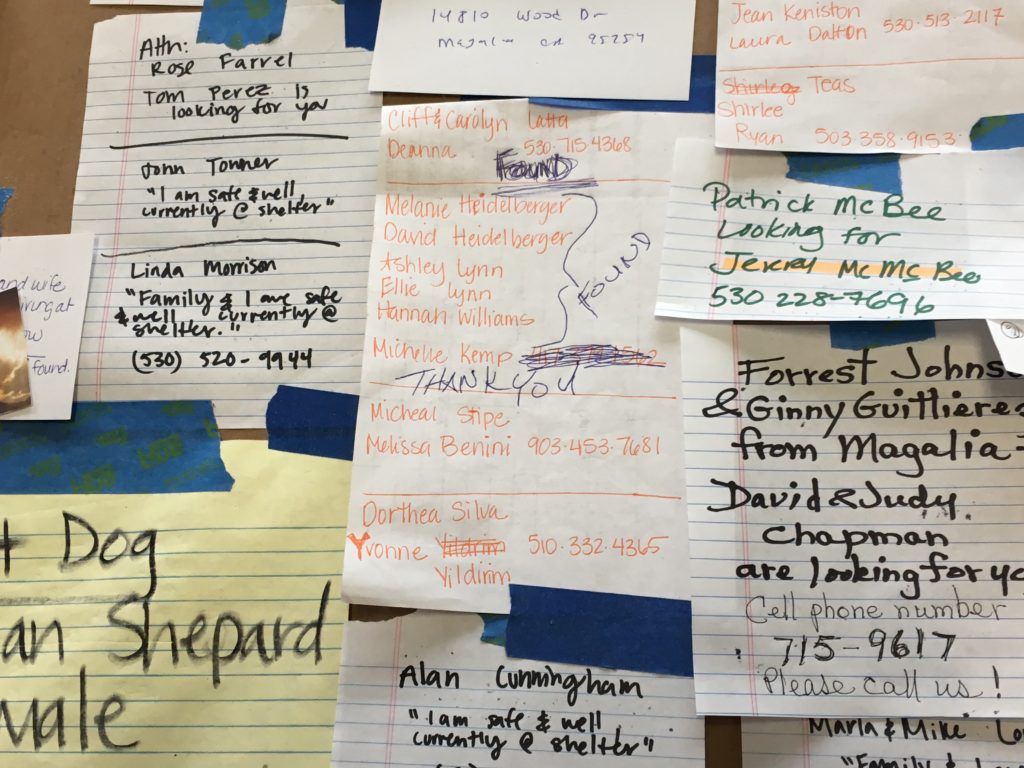

Diana Lambert / EdSource

A table at the evacuation center in Gridley is filled with notes from people looking for friends, family members and pets.

Cal-Fire officials say the Camp Fire is now 45 percent contained, but it and another fire burning in Southern California continue to wreak havoc throughout the state. Smoke from the fires has forced the closings of 180 K-12 districts serving approximately 1.1 million students, according to a tally by the news organization CALmatters. Colleges and universities throughout the state have also closed.

Almost simultaneous with the Camp Fire, the Woolsey Fire tore through highly populated sections of Ventura County and northern Los Angeles County, killing three people. That fire, which is now 63 percent contained, destroyed nearly 500 homes and damaged the campus of Ilan Ramon Day School, a private Jewish school in the Los Angeles County city of Agoura Hills. Three school districts in the area — Conejo Valley Unified, Las Virgenes Unified and Oak Park Unified — are closed until after the Thanksgiving break.

Uncharted territory

In Butte County, which is about 80 miles north of Sacramento, all schools will remain closed until Dec. 3. Meanwhile, officials will continue working to find new schools for an entire district of students.

“It’s still early, but we’re operating under the assumption that schools in Paradise will not re-open,” said Sheri Hanni, the county office of education’s School Attendance Review Board coordinator. “We’re trying to determine how many of the students will stay in the county and where they’ll be — that’s where we’re at right now.”

During a Friday afternoon press conference, Butte County Superintendent Tim Taylor said 100 portable classrooms are needed countywide to house students whose schools were damaged or destroyed in the fire.

“If we can quickly re-build the Bay Bridge after an earthquake, we can get 100 portables up here,” Taylor said, referring to the re-building efforts following 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that struck the Bay Area.

Relocating displaced students after fires, earthquakes, floods and other disasters is far from new to school districts in California.

Finding new schools for students after last year’s Tubbs Fire — which leveled large swaths of the city of Santa Rosa and, until the Camp Fire, was the most destructive in state history — required a Herculean effort from officials and staff in districts and agencies throughout Sonoma County. The Carr Fire, which choked the California/Oregon border in July and August, disrupted the beginning of the school year in Shasta and Trinity counties.

But given the complete destruction of Paradise, the town’s geographic isolation and the relative lack of resources in Butte County, officials there and in surrounding counties are, in many respects, entering uncharted territory.

“The challenge now is to figure out where those students will go to school and it is really difficult to figure that all out,” said Rich DuVarney, the superintendent for the office of education in neighboring Tehama County. “Families have scattered and each has a different situation — some will move to another state, some will stay put in Butte County.”

Ariya Boone isn’t sure her family will return to Paradise. The three boys — 2nd-, 4th- and 5th-graders — no longer have a school to attend. Their home and their computer business have burned to the ground. Even if they could afford to reopen Andrew’s Tech Service, there are no clients.

Melanie Heidelberger plans to return to her home in Magalia, just five miles north of Paradise, but isn’t sure how long it will be before it is safe and water and electricity are back on. For now, she and her extended family are living in tents on the Butte County Fairgrounds in Gridley.

Her daughter, Hannah, a freshman at Paradise High School, misses her friends. She is resigned to attending the high school in Gridley or Chico while infrastructure in Paradise and Magalia, a town of about 11,000, is restored.

“It’s all up in the air because a lot of families don’t know where they will live,” Hannah said.

Diana Lambert / EdSource

Melanie Heidelberger and her daughter Hannah are part of an extended family camping out at the evacuation center in Gridley. Their house in Magalia is still standing, but conditions are too unsafe for their return.

Help streaming in

Such realities were on the minds of 300 state, county and local officials who gathered in Chico on Wednesday to get an assessment of the damage and begin planning for the weeks and months ahead. State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson attended the meeting and later toured evacuation sites.

He pledged state support on multiple levels and said his office has already begun applying to a federal grant program that provided about $14 million to state and local agencies in the aftermath of the Santa Rosa fire. Also, Taylor, Butte County’s superintendent, has established a relief fund that will go toward buying up to 5,000 laptop computers for Paradise Unified students.

“This was considered very important,” Torlakson said. “The computers will help students get in touch with teachers and keep up with their lessons.”

Additionally, DuVarney said, displaced students will be covered under the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, a 1987 federal law that, among other things, allows students who are homeless to enroll in school without having to show proof of residency or immunization records.

“This would, for example, cover a family living temporarily in a Wal-Mart parking lot,” DuVarney said. “They would be able to enroll in that neighborhood school without proof of residency and also qualify for free and reduced lunch.”

State law also allows Torlakson to authorize continued funding for Paradise Unified schools even though they won’t be reporting daily attendance figures, which are used to allocate money to California schools. Other schools in the region, which had to close due to poor air quality, will also likely receive waivers for attendance requirements.

Many Paradise Unified teachers and other staff members also suffered incalculable losses — losing both their home and workplace in the fire. Both Torlakson and DuVarney acknowledged that they’re unsure what will happen with district employees going forward.

“We’ll have teachers coming back to schools and there aren’t any students,” Torlakson said. “We can’t just lay the teachers off, that wouldn’t be right…we know they need help too. They will have to counsel the children but hundreds also lost their homes.”

Underlying all of these logistical issues is a tremendous amount of trauma that will have to be addressed. Counseling and mental health professionals are mobilizing — many showed up to Wednesday’s meeting and another that was held on Tuesday, Hanni said.

One silver lining is that counselors, social workers and psychologists who dealt with the mental health effects of the Santa Rosa fires can bring their lessons learned to Paradise. Mandy Corbin, the assistant superintendent for special education at the Sonoma County Office of Education, said her staff has already reached out to Butte County officials.

Corbin said it is crucial that key people receive trauma-informed training before the students come back and that families and school staff are made aware of the resources available to them.

“If people don’t know where the resources are they may shut down and not ask for help,” Corbin said. “We have to make sure resources are there for the entire school community and clearly delineated.”

Ariya Boone is doing all she can to help her children cope with their losses in the meantime.

“We try to frame it as positively as we can and say, ‘Yes, your loss is real. Yes, it hurts and yes, we have to rebuild. But not all is lost. We have each other. We are together.’”

David Washburn writes about school climate and discipline issues in California. Diana Lambert is based in Sacramento and writes about teaching in California.

This story was updated to reflect current damage estimates to Paradise Unified Schools, provide new information on school closures and include comments from Butte County Superintendent Tim Taylor.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments (14)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Vicki Stenken 5 years ago5 years ago

I am a retired teacher and am willing to come and help teachers prep their rooms or their school. I live in Sacramento

SCOTT GUTHRIDGE 5 years ago5 years ago

We are a small library in Nevada and have enough materiel to start a small school and are not sure what to do with it all. If the schools would want a donation of readers and such please let us know. I will gladly deliver them to you.

Kerry 5 years ago5 years ago

I am retired K-2 teacher due to accident with garage full of books, materials, classroom supplies, files cabinets etc. If I can help I would love to give to teachers who have lost their classrooms.

Anita 5 years ago5 years ago

I have recently retired from teaching and have many books/materials I can donate to the schools destroyed by the fires. Please let me know how to do that.

Karen Wright 5 years ago5 years ago

I am a Grass Valley bookseller who gave several bags of books to the Camp Fire folks. I’m cleaning my shelves of some kids book and will have 3-4 more boxes of children’s books to donate, but don’t know who to contact. You can reach me at wrgtbook@yahoo.com.

Julie Peterson 5 years ago5 years ago

I live in Moses Lake, Wa and grew up in Redding. I was able to raise $3000.00 for the Carr Fire and I went down to Redding to help. I bought a ton of back to school stuff and distributed back packs and supplies. I am now doing a fundraiser to help where needed in Butte County. I have not seen a lot on Facebook about back to school supplies so I … Read More

I live in Moses Lake, Wa and grew up in Redding. I was able to raise $3000.00 for the Carr Fire and I went down to Redding to help. I bought a ton of back to school stuff and distributed back packs and supplies. I am now doing a fundraiser to help where needed in Butte County. I have not seen a lot on Facebook about back to school supplies so I have decided to do a school supply drive called “Backpacks for Butte”. I don’t know how many I will get but hopefully it will be successful and needed. I will be down there the second week of December to distribute.

Replies

Wayne MacMartin 5 years ago5 years ago

Julie,

Like you, I have been moved to help with this terrible tragedy. Our company is in the school supply business and I had an interest in reaching out to vendors to see what could be donated to assist with the fires. Please let me know if you would like some assistance.

Mandy 5 years ago5 years ago

Please let us know if we can help! We are currently doing a book donation drive at Barnes and Noble …. would love to donate books to help rebuild their library’s .

Sherry 5 years ago5 years ago

I know he mentioned that laying off teachers would not be right but with an entire town destroyed and no people and no tax dollars coming in, how do you continue to keep them on the payroll? As a teacher myself, I would like to see this story followed. I am looking to send donations to those teachers in the Paradise School District.

Cvincent 5 years ago5 years ago

Please post locations teachers can donate books or other teaching materials.

Elizabeth Monson 5 years ago5 years ago

As a therapist having assisted in trauma events this is beyond the current resources. Connect with computers. Mobil housing and get the health departments there. I have been to what WAS paradise California

Jenny 5 years ago5 years ago

Is the school district’s administrative offices still standing?

Replies

David Washburn 5 years ago5 years ago

Hi Jenny,

We were able to confirm that the district office was damaged, but we don’t know the extent of the damage.

Liz 5 years ago5 years ago

Please let people in the broader CA and US community know how we can help????