Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Last month, a legislative committee launched the first of a series of year-long hearings into possibly updating the state Master Plan that has guided higher education policy in California for the last 70 years.

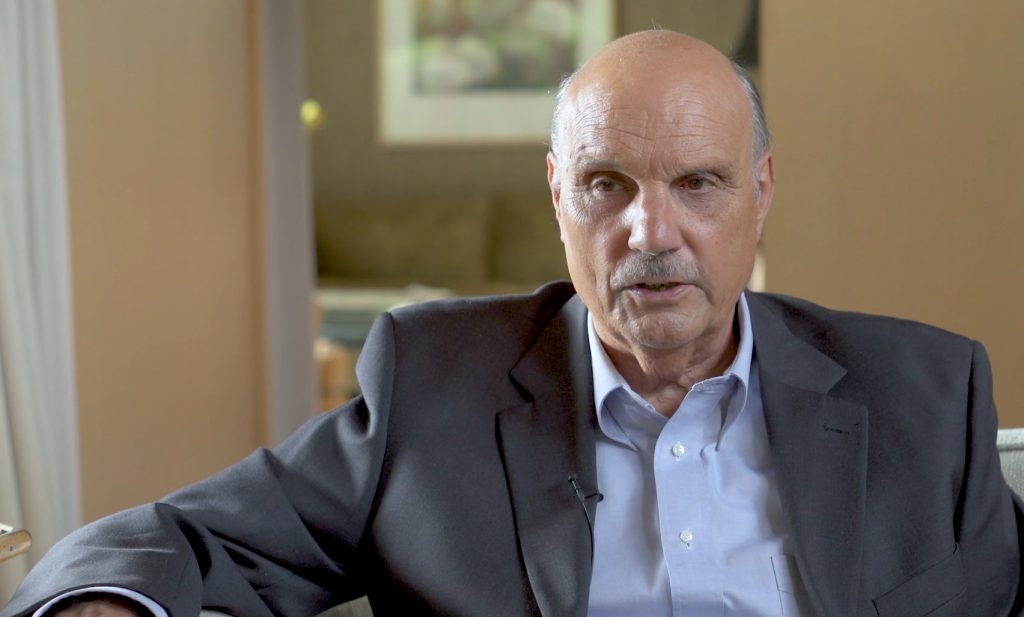

But after examining the state of higher education closely in Silicon Valley and the wider Bay Area, State Board of Education President Michael Kirst concluded that what’s really needed — at least in that area of the state if not others — is a regional approach to address higher education’s shortcomings and challenges. Only a regional vision, led by a new regional entity, can fix gaps in supply in one of the most dynamic economies in the world, where demand for well-educated employees is constantly shifting, with critical short- and long-term labor shortages projected.

“The California Master Plan is clearly outmoded for the dynamic needs of modern (and mobile) students” needing support for lifelong learning and a fast-changing economy, Kirst, co-author Richard Scott, and contributing authors write in their newly published book titled Higher Education and Silicon Valley: Connected but Conflicted (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017). “We believe that Bay Area leaders cannot wait for federal and state leaders to take action on their behalf.”

For eight years, as state board president, Kirst has overseen massive changes in school financing, academic standards and accountability under Gov. Jerry Brown. But, as a Stanford University emeritus professor in both education and business administration, he has also pursued a career-long professional interest in figuring out how K-12 schools and segments of higher education could fit together better and how they, in turn, could better prepare students and workers for job and career opportunities. That’s what he and Scott, a fellow emeritus professor at Stanford, attempt in the new book.

The conclusion of Kirst and his co-authors is that the state’s public universities and Bay Area employers are too much out of sync. Certainly there are synergies and successes: Stanford, UC Berkeley and UC Santa Cruz generate MBAs and entrepreneurs, ideas and research. San Jose State University graduates 600 to 700 engineers each year, mostly for Silicon Valley companies, and by far the most CSU master’s degrees in software and computer engineering. Foothill College has opened a new community college satellite at Moffett Field, by Google and NASA Ames in Sunnyvale. Bay Area high schools are among those benefiting from the more than $1 billion invested in career pathways programs offering college credit and work experiences.

Yet higher education institutions, particularly public colleges and universities, and the Bay Area economy are “mismatched in many ways, and ill-suited for each other. The two fields have developed under different conditions, with different pressures, for different purposes,” the authors write. The mismatch “is important to address because it threatens the supply of skills and knowledge needed for economic growth and civic vitality in the region.”

Driven by changing technologies over the past half-century, Silicon Valley industries morphed from defense to semiconductors to personal computers to internet companies, social media, biotech and cybersecurity. Companies hired immigrants to fill many of the jobs demanding higher education, as the region’s public colleges and universities could not keep up with the demand, student demographics and fast-changing training needs, the book says.

The book’s research covered colleges and universities serving 7 million people in seven of the Bay Area’s nine counties: Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, San Mateo, San Francisco, Marin, Alameda and Contra Costa. It focused on four academic areas: computer science; biology and biotech; business administration; and engineering.

The authors found that popular programs in the region’s community colleges and three public California State Universities were often “impacted,” meaning unable to accept new enrollments, and qualified transfer students couldn’t find openings in their majors. Contra Costa County, with a million-plus people, has no CSU, although the city of Concord does have a satellite campus of CSU East Bay.

State underfunding is an issue; inflation-adjusted state support has fallen significantly since the mid-1970s for UC and somewhat for CSU. Community colleges have disincentives to expand high-demand vocational programs like mechanics because the state funding is tied to enrollment, not program cost, the book says. And funding is cyclical: Budget cuts hit public colleges at the worst time, when layoffs and hiring slowdowns lead more workers to seek retraining and college degrees.

Online education opportunities, open source educational resources and other technologies may transform learning but haven’t yet substantially reshaped the delivery of higher education, the authors say. “Just try to get to any of the three CSUs (San Jose State, San Francisco State or CSU East Bay in Hayward) after you work a full day,” Kirst said in an interview.

Community colleges, CSU and UC are governed and operate independently, and a lack of coordination obstructs the needs of the growing numbers of middle-age students with families and commutes, the authors say. Their ranks include “accelerators,” students looking to improve their skills, and “industry switchers” looking to change careers. Caught in the middle are what Kirst and the authors call “swirlers,” those who, depending on their needs, enroll back and forth from community college to a CSU — only to encounter credit and enrollment road blocks.

As Mohammad “Mo” Qayoumi, the former president of San Jose State, told Kirst, “I struggled to change this institution incrementally. The external economy changes exponentially.”

For-profit and private nonprofit colleges recognized opportunities to fill the gaps. Dozens have set up shop in the Bay Area, from Northwest Technical College in Hayward, training Mandarin speakers, to larger privates like University of Phoenix and DeVry University.

Researchers found more than 350 higher ed schools in the Bay Area in 2015. Many of the private colleges operate under the radar; 80 percent of for-profit colleges aren’t listed in the primary national higher ed data base. Regulated by the State Bureau of Consumer Affairs — not a higher education authority — they are subject to fewer constraints. They have pushed online learning, responded more quickly with vocational courses in areas of labor shortages, and hired “success coaches” to work with students. But many are, Kirst said, “diploma mills.” They overpromise, overspend on marketing and graduate few students, with many of them racking up big debts, he said.

However, taking the lead from private colleges’ innovations, public colleges and universities should create new designs for degrees and certificates that recognize “nanodegrees” and “digital badges” received through short-term training and high-tech “bootcamps” that have sprung up in San Francisco and Oakland. Those with a high level of measurable quality should be transferable toward a degree, the authors suggest.

They recommend that state colleges begin offering applied bachelor’s degrees, which allow for technical or occupational course work to count toward a four-year degree. Thirty-nine states grant them, but not CSU. Community colleges could offer applied degrees, or CSUs could create “hybrid” operations, starting with a two-year satellite campus affiliated with a community college.

Kirst’s primary recommendation is for mayors, and business and education leaders to create a regional agenda for education policy in the Bay Area, with a new entity “to develop a vision and see it through.” It would estimate the postsecondary investment needed to meet regional academic and vocational demands and coordinate the efforts of public and private colleges, K-12 adult education programs and the state’s Workforce Investment Boards. Two regional agencies, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, which coordinates Bay Area transportation financing and planning, and the Association of Bay Area Governments, a voluntary organization, offer potential models, Kirst suggests.

“We hope to begin a conversation that takes a broad view of the relationship between higher education and the economy,” Kirst writes in a summary of the book.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Luis Valentino 7 years ago7 years ago

John, great article. This story reflects an issue that will only worsen if not addressed in a comprehensive and systemic way, creating a gap between what and how students learn, and the needs of the industries in the region. When I served as Chief Academic Officer with the San Francisco Unified School District, one of the areas of concern and action was the alignment of our CTE and internship programs with the industry … Read More

John, great article. This story reflects an issue that will only worsen if not addressed in a comprehensive and systemic way, creating a gap between what and how students learn, and the needs of the industries in the region.

When I served as Chief Academic Officer with the San Francisco Unified School District, one of the areas of concern and action was the alignment of our CTE and internship programs with the industry sectors in the Bay area. Our partnerships with the community colleges, universities and industries in the region provided us with great information and an opportunity to better understand the needs in San Francisco. This allowed us to provide the most authentic and relevant learning experiences for our students. It suggests the importance of including K-12 districts in conversations related to reimagining California’s Master Plan for Higher Education so that we can ultimately create a seamless preK-20 continuum that best prepares students to succeed across the industry sectors that make up the economy of the Bay area and California.

Gabe 7 years ago7 years ago

I enjoyed and learned a lot during my tenure at the University of Phoenix. Truly an amazing and meaningful education that was immediately applicable and relevant. And my education at the University of Phoenix was better than any education at public state universities I’ve attended. No University paid attention to the non-traditional student but the University of Phoenix! When I attended, they worked hard to ensure I succeeded and I have.