Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

For California’s local schools, the availability of educational data is undergoing dramatic change, and along with it, the politics of how to use that data.

Improving student outcomes requires improving instruction and services in classrooms and schools. The state’s new educational initiatives, including the Local Control Funding Formula, recognize that improvement happens locally, so there has been an intentional focus on access and use of data locally for improvement efforts.

This theory of action runs counter to a long-held belief by researchers that education data must be closely controlled by, and flow from, the state. The truth is California’s reliance on multilevel data systems have profound implications not only for researchers, but also for policymakers and the public seeking information about educational progress.

As a co-founder of Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE), a nationally recognized research center, I once championed the notion that, even if they are far from classrooms, researchers with sufficient data are well equipped to inform and influence policymaking. While there is still truth to that premise, California is trailblazing new supplemental, local alternatives that create new data systems for varied local uses.

California is at the forefront nationally in requiring local accountability plans that outline local goals, describe spending plans and measure annual progress locally. Now, in addition to accessing state-centralized data through state systems, researchers, policymakers and school communities are accessing new data networks and resources locally.

Affirming this bold new process change, the Legislature and the governor recently appropriated $24 million to the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE) to build local capacity around local accountability plans and the state’s new evaluation rubrics, which reflect a balance of state and local measures. The goal is to empower local networks of educators, parents and stakeholders to use data within their local accountability plans and rubrics that can be tailored to local circumstances. These new accountability tools are reversing how data is collected and shared in education systems. While the formats of the Local Control and Accountability Plans are state-directed, the data is locally-driven. It is being collected, evaluated and put to use closest to where learning and teaching is happening and advocacy for change is most efficient.

One California network gaining national recognition for its work locally is the CORE Districts. These districts, situated in Fresno, Garden Grove, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Francisco and Santa Ana, have established a data system to support school improvement efforts locally. The districts work with researchers to identify strengths and weaknesses and improve outcomes for the one million students they serve. The CORE data system includes an array of locally-driven information such as high school readiness and students’ social emotional skills, the latter measure gaining considerable attention in California and throughout the nation.

Significant work lies ahead for many types of groups to support districts and schools while they adjust to this new local context of data collection and use. A priority is to ensure that state and local data in the new evaluation rubrics is used to better inform local accountability plans and to communicate with stakeholders about the progress schools are making.

The dashboard of state-required measures, such as readiness for college and careers, test scores, graduation rates and progress of English learners, coupled with measures that are collected locally and reported to the state, will help. The rubrics will also link to statements of model practices: research-supported and evidence-based practices that can help local educators analyze progress as they review their performance data.

Collaborative transparency among adults to ensure improved outcomes for students will not happen overnight. But it will broaden data analysis and awareness and help lead to greater equity for all students.

In addition to accountability tools, California has invested heavily in generating data to improve teaching and learning.

The statewide Smarter Balanced assessment is an instructional improvement tool as well as a test of students’ college and career readiness. More than $4 million per year is being spent to support Smarter Balanced online resources, assessment tools and the Digital Library, all available to California’s 300,000 educators.

Resources in the digital library incorporate ideas for teachers to find and use new content and pedagogy to enhance student learning. They describe activities that teachers can implement to monitor progress and solicit student feedback through one-on-one questioning or task-based activities. Data used this way supports teachers with ongoing, meaningful instructional adjustments to improve student learning.

More students, parents, educators and stakeholders are involved in educational decision-making than ever before. To help, the State Board of Education will work to continuously improve new data tools and support local networks – and researchers will continue to have a valuable role in analyzing state and local data, empowering educators and stakeholders, and informing policymakers.

•••

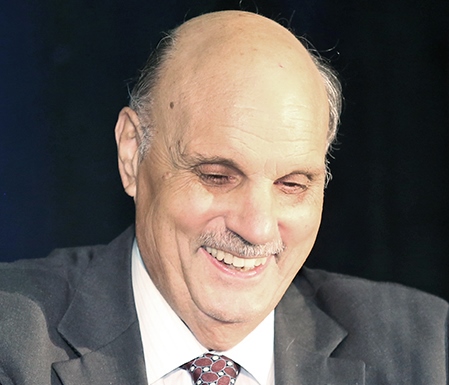

Michael Kirst is President of the California State Board of Education and Professor Emeritus of Education at Stanford University.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

Comments (2)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Doug McRae 8 years ago8 years ago

Three observations: First, on the "Strong locally generated data" headline, how will we ever know whether the local data will be strong, or even just valid reliable fair as stipulated by statute? I've heard nada on this aspect of local data contributing to LCAPs to date. Second, on "the politics of how to use that data" in the first sentence, at least in theory the data should be impartial, not the result of political manipulation. … Read More

Three observations: First, on the “Strong locally generated data” headline, how will we ever know whether the local data will be strong, or even just valid reliable fair as stipulated by statute? I’ve heard nada on this aspect of local data contributing to LCAPs to date. Second, on “the politics of how to use that data” in the first sentence, at least in theory the data should be impartial, not the result of political manipulation. Third, on the “Smarter is an instructional tool” paragraph toward the end of the commentary referring to Smarter’s Interim Tests and Digital Library, nearly two years after introduction of these tools we still have no meaningful information on whether these tools are being widely used in the trenches much less whether they are having a positive impact on student achievement. The jury is still out on CA’s new approach to K-12 assessments and accountability.

SD Parent 8 years ago8 years ago

Yes, a student is more than a test score, and the same can be true for a school. But school districts, schools, and teachers are not experts in metric design and data analysis. Allowing flexibility of a dozen or more different metrics just obfuscates the only metrics that really count: are students actually learning the material, and are they prepared for college and/or career? Flexibility also allows districts to focus on metrics … Read More

Yes, a student is more than a test score, and the same can be true for a school. But school districts, schools, and teachers are not experts in metric design and data analysis. Allowing flexibility of a dozen or more different metrics just obfuscates the only metrics that really count: are students actually learning the material, and are they prepared for college and/or career?

Flexibility also allows districts to focus on metrics that are tangential (e.g. look, our suspension and expulsion rates have dropped!) and completely ignore data that they don’t collect that might shine a spotlight on areas that should be addressed. For example, SDUSD is no longer doing Directed Reading Assessments in elementary schools to see whether students are making progress and whether they are closing the achievement gaps. The district also no longer offers standardized interim assessments (each school now writes its own), which limits the measurement of achievement gaps since affected populations are not distributed equally across the district.

CORE districts are working with researchers to design genuine metrics. But with so much flexibility, who oversees that the metrics for all other school districts are designed well, truly relevant, and well-controlled?