A new one-of-a-kind robotics middle school in Los Angeles is not only offering students a hands-on curriculum but providing skills that could help them someday transform almost every aspect of modern life.

This fall, Los Angeles Unified School District launched the Mulholland Robotics Middle School. It may well be the only one of its kind in the country.

Mulholland is one of several new L.A. Unified magnet schools aimed at reversing steady enrollment declines as a result of numerous factors, including declining birth rates and competition from charter schools.

Magnet schools differ from traditional neighborhood schools in that their curricula are based around a specific subject such as science, the arts, firefighting, journalism and now, robotics. They are open to any family living in the district, although competition to get into them can be fierce because of limited space. Some have their own campus; others operate within an existing traditional school.

Sean Carlsson, 12, couldn’t be happier to be going to a school where he learns about making robots that find people buried in the rubble of an earthquake or learns computer principles for preventing cyber attacks.

“I’m interested in how hacking occurs,” said Sean, who dreams of defending the U.S. from illegal break-ins into government computers. “I want to defend the U.S.”

“We used to be the school that everyone ran away from,” said Gregory Vallone, who was recruited as Mulholland’s principal with the directive to turn it around.

A decade ago, student enrollment in Mulholland, a middle school in the Los Angeles suburb of Van Nuys, began to decline. It fell by 40 percent, from nearly 1,900 students in the mid-2000s to 1,130 in the 2014-2015 school year.

Two years ago, forecasts showed that the school’s enrollment would drop further, to 950 students this school year (2016-2017).

“We used to be the school that everyone ran away from,” said Gregory Vallone, who was recruited as Mulholland’s principal with the directive to turn it around.

Vallone got the idea for the robotics school after reading remarks by Microsoft’s Bill Gates, who compared robotics to the software industry of the 1970s in terms of its potential for growth. Research conducted by Connecticut-based Gartner Inc., an information technology research company, found that by 2030, smart machines would replace 90 percent of jobs.

Vallone successfully pitched a robotics program last year to then-L.A. Unified board member Tamar Galatzan, who was impressed enough to authorize $150,000 of her discretionary bond funds to build a robotics lab and an after-school program.

This year, the program became a magnet school within the larger traditional school at Mulholland, which also includes a police academy magnet. The robotics program immediately attracted 200 6th- and 7th-grade students.

Vallone bought robotics curriculum and robot kits from Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Academy in Pittsburgh. As one of the first projects, students built robots with rollers and mechanical arms. The school also is building a huge water tank for students to test submersible drones and is clearing an adjacent field for students to try out aerial drones.

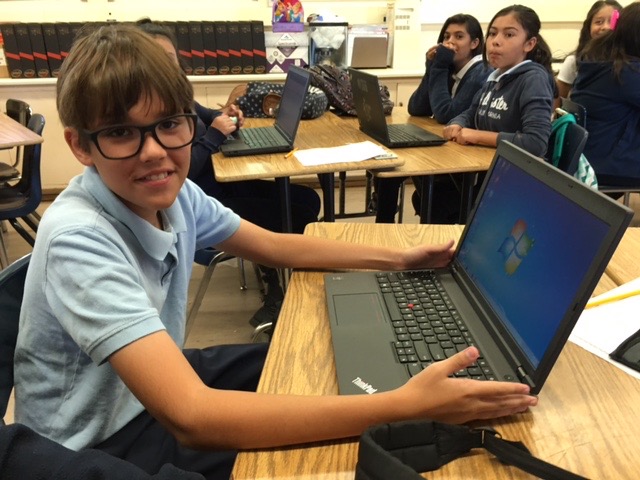

Credit: EdSource/Pat Maio

Sixth-graders Jennifer Rozell, left, and Michelle Valeriano, both 11, are attempting to repair the claw on a miniature robot that they built at Mulholland Middle School.

Robotics are included in every class, including English, math, history and science. For example, students were asked to write a paper for an English class in the first few weeks of school this year that explained how a robot could have saved lives in a 9.2 magnitude earthquake that jarred Alaska in 1964.

In a math class, the kids were asked to estimate how far a tectonic plate could shift in 12 years if geologists estimate that plates could shift six inches annually. The math question didn’t have a direct tie-in with robotics, but it was part of the school’s curriculum to relate the students’ robotics-building efforts with the lesson on the Alaskan earthquake.

The math question also was one part of the overall theme of the school, where the lesson on earthquakes included students building a robot, then writing a paper about how the robot could be used to save lives, and finally using math skills to determine how far a robot might travel to help save lives or dig to reach people.

Earlier this month, several students tested robot rovers they built, making sure the computer code delivered the correct commands. The rovers are shoebox-sized boxes that resemble cars erected out of metal plates, axles, wheels, a tiny battery and electronic circuitry needed to control how far and fast they move. The rovers grip objects with a claw that moves in all directions.

About 30 students tested out their robots in class, gathering around the devices they built in teams of two. Sixth-grader Michelle Valeriano, who built her robot with Jennifer Rozell, was frustrated that she couldn’t get it to work.

“We weren’t able to get the arm to move up and down. We can close and open it, but that’s it,” said Michelle, who turned the robot over on its side to work on one of the claws with Jennifer.

“What I’m hoping is that the success of the program leads to more innovation within LAUSD,” said Keith Abrahams, executive director of the district’s student integration services and magnet schools. “My gut tells me I’ll have more neighborhoods and communities that want to develop this type of robotics program in their schools.”

Magnet schools began opening in 1978 as part of a voluntary desegregation plan designed to stem white flight from the district.

L.A. Unified now has 214 magnet programs, a third of them opening since 2009 and 16 this year alone, with plans to add 13 more in 2017, according to Superintendent Michelle King, who said in a speech last month that she views magnets as part of the larger strategy to increase enrollment.

Jennifer, 11, said she likes that challenges posed by the school have placed her on the same ground as boys.

She said that tinkering with the robot and solving problems like getting the robot’s claw to work properly are important because of her career aspirations. She wants to become an astrophysicist and use robotics to take photos and soil samples a universe away.

“I like coming to this school because it shows boys that girls can make robots as well,” she said. “It’s good for girls to do this.”

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.