Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

It seemed a straightforward enough goal: define what it means for a child to be ready for kindergarten. But when a bill to establish a kindergarten readiness standard was introduced in the Legislature in February, several child development and early education experts objected, suggesting it could push preschools to become overly and inappropriately academic.

Although the bill has since been altered, concerns remain. Critics say the bill doesn’t include a way to measure whether the standard is being met and that it is still too academic, veering away from play-based learning they believe is more appropriate for preschool-aged children.

The bill, AB 2410, was introduced by Assemblyman Rob Bonta, D-Oakland, and had two main components. It would have required the California Department of Education to submit a kindergarten readiness definition, based on the input of a 10-person committee, to the State Board of Education by July 2018. And it would have allowed preschools to obtain a waiver from assessing the development of each child, known as the Desired Results Development Profile, or DRDP, that state-funded preschools in California are mandated to undertake twice a year.

Bonta said his approach was a common sense step toward ensuring low-income students and those learning English get an equal shot at academic success by establishing at an early stage whether they are being properly prepared for school. It would also, he said, spur innovation at the local level because preschools would have to devise and get approval for their own assessments in order to get a waiver from the state-mandated assessment.

“I think it definitely makes it less burdensome — it’s a really, really good step in the right direction. Does it get us all the way? That’ll be decided,” said Assemblyman Rob Bonta, D-Oakland.

The latest version of the bill retains the requirement for a kindergarten readiness definition by mid-2018. But it no longer allows a waiver from the assessment. That provision was eliminated in the Assembly education committee because the California Department of Education is streamlining the assessment in response to concerns raised about it.

Bonta said he considered that development a win.

“I think we were able to strengthen the bill and accommodate and recognize some of the changes that CDE is doing on its own,” he said.

Bonta and the bill’s advocates consider the assessment preschool teachers must complete overly long, laborious and repetitive and say it rarely leads to better instruction.

The assessment currently includes eight focus areas, or domains. The Department of Education said it will cut that number to five. The mandatory domains will be: approaches to learning; social and emotional development; language and literacy development; cognition; and physical development-health. The department will also reduce from 54 to 29 the number of subject areas within those domains that teachers must assess.

“I think it definitely makes it less burdensome — it’s a really, really good step in the right direction,” Bonta said. “Does it get us all the way? That’ll be decided.”

He said he will continue to seek input – including from preschool and kindergarten teachers – to revise the assessment, and he maintained that the bill contains room to spur new approaches.

AB 2410 has prominent supporters, among them Deborah Kong, executive director of the advocacy organization Early Edge, who said a kindergarten readiness definition would lead to better preschools and help close the achievement gap between poor students or those learning English and those from generally white and higher- income households.

“The promise of early learning can only be realized if programs are of high quality and that’s a really important way to explore whether programs are of high quality,” Kong said. She added, “Standards inform curriculum, and that’s a key building block of quality.”

She also said she approves of the Department of Education’s move to reduce the scope of the mandated assessment. “It really removes a barrier that is time-consuming for teachers and takes away from teacher-child interaction in the classroom.”

But the changes have not allayed criticism from others in early child education and development.

Jade Jenkins, a UC Irvine assistant professor of early childhood policy, said the bill is largely unnecessary because other, effective tools already exist, including the Devereaux, Achenbach and preLAS assessments. She also said it is unhelpful because it leaves in place the mandatory state assessment, which she said is not highly regarded.

“Most people don’t consider it useful,” Jenkins said. “It’s more a screener, more about capturing potential developmental delays or issues with a child; it’s not about assessing how skillful they are in any of these domains.”

A kindergarten readiness definition essentially sets a standard, Jenkins said, and would need a “valid and reliable instrument” to assess whether it is being met. The current assessment is not that instrument, she said, and without one, the standard is pointless.

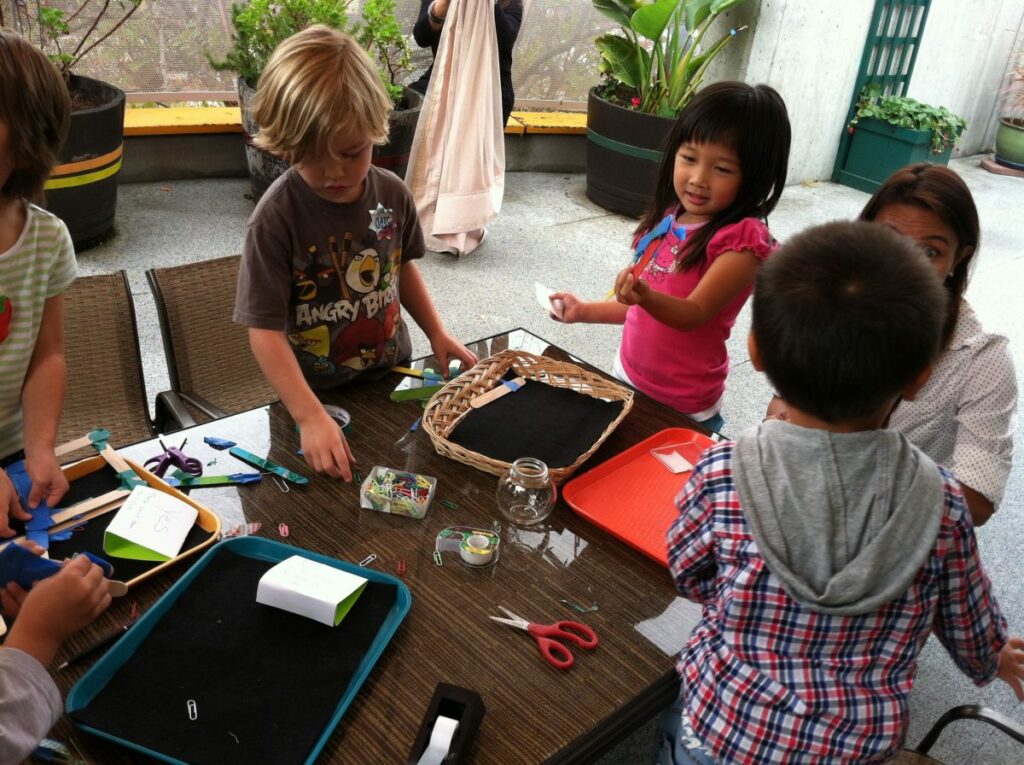

“What happens is because preschool teachers feel this pressure, they tend not to use play-based learning activities and to use worksheets and do them repeatedly. It’s not child-centered, it’s not a child actually having meaningful experiences and developing skills in meaningful ways,” said Ruth Piker, an associate professor at CSU Long Beach.

Among others, concerns remain that defining kindergarten readiness moves toward making preschool inappropriately academic at too early an age.

“What happens is because preschool teachers feel this pressure, they tend not to use play-based learning activities and to use worksheets and do them repeatedly,” said Ruth Piker, an associate professor at CSU Long Beach. “It’s not child-centered, it’s not a child actually having meaningful experiences and developing skills in meaningful ways.”

Piker, an expert in early child education and curriculum and assessment, also said a readiness definition would not take into account the environmental and other non-school factors that shape a child’s abilities and preparedness, nor provide clear direction for how preschool teachers could better help students get ready for kindergarten.

“I just don’t understand the purpose behind it,” she said of the bill.

Bonta rejected the criticism, and expressed frustration about it.

“This is about a kindergarten readiness definition, period. It’s not about kindergarten readiness testing, there’s no assessment component,” Bonta said. His bill includes no test for a student to progress from preschool to kindergarten, he said, adding, “It’s a guidepost for the preschool, it’s not a threshold for kindergarten entry, it’s not a bubble test, it’s not a boot camp for kindergarten. That’s nowhere in my bill.”

Scott Moore, executive director of Kidango, the Bay Area’s largest early education services provider, was one of several people who provided input as the bill was being written. He said he understands where critics are coming from, but that their concerns can be addressed through proper implementation.

“Absolutely those concerns are real and legitimate,” he said. “But we have to balance those concerns with the concern for low-income children who are coming to school with the achievement gap already in place.”

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

Comments (1)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Debbie O'Neill 8 years ago8 years ago

The low income Spanish speaking students that enter my kindergarten classroom are ready to learn if they had any school experience. It does not mean that they come in knowing their letters and numbers. They come with more language from academic play...rhymes, songs, social skills. The problem I must face is the lack of preschool space. Every year we enroll about 220 K students and half have had no previous school … Read More

The low income Spanish speaking students that enter my kindergarten classroom are ready to learn if they had any school experience. It does not mean that they come in knowing their letters and numbers. They come with more language from academic play…rhymes, songs, social skills. The problem I must face is the lack of preschool space. Every year we enroll about 220 K students and half have had no previous school experience. Are other districts experiencing this situation? Many parents have stated they are on waiting list. Do we now mandate preschool? Those parents that do not want can “homeschool” their own.