Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

In “The Pout-Pout Fish” children’s picture book, the author weaves words like “aghast” and “grimace” into a story about a fish who thought he was destined to “spread the dreary-wearies all over the place” until…well, no need to spoil the ending.

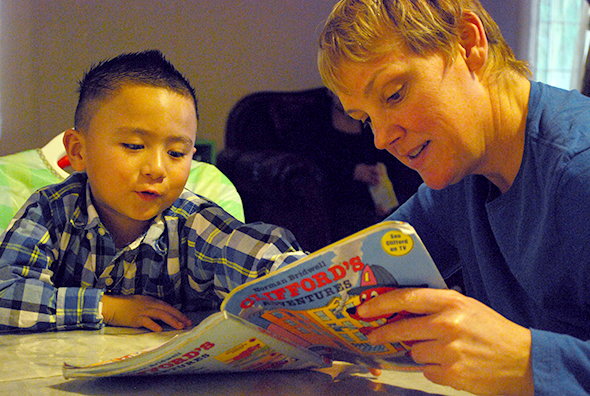

Finding such rich language in a picture book is not unusual, and reading those stories aloud will introduce children to an extensive vocabulary, according to new research conducted by Dominic Massaro, a professor emeritus in psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He said although parents can build their children’s vocabularies by talking to them, reading to them is more effective.

Reading aloud is the best way to help children develop word mastery and grammatical understanding, which form the basis for learning how to read, said Massaro, who studies language acquisition and literacy. He found that picture books are two to three times as likely as parent-child conversations to include a word that isn’t among the 5,000 most common English words.

Picture books even include more uncommon words than conversations among adults, he said.

“We talk with a lazy tongue,” Massaro said. “We tend to point at something or use a pronoun and the context tells you what it is. We talk at a basic level.”

Liv Ames for EdSource

Books by Dr. Seuss are popular with children.

Massaro said the limited vocabulary in ordinary, informal speech means what has been dubbed “the talking cure” – encouraging parents to talk more to their children to increase their vocabularies – has its drawbacks. Reading picture books to children would not only expose them to more words, he said, but it also would have a leveling effect for families with less education and a more limited vocabulary.

“Given the fact that word mastery in adulthood is correlated with early acquisition of words, shared picture book reading offers a potentially powerful strategy to prepare children for competent literacy skills,” Massaro said in the study.

The emphasis on talking more to children to increase their vocabularies is based on research by Betty Hart and Todd Risley at the University of Kansas. They found that parents on welfare spoke about 620 words to their children in an average hour compared with 2,150 words an hour spoken by parents with professional jobs. By age 3, the children with professional parents had heard 30 million more words than the children whose parents were on welfare. Hart and Risley concluded that the more parents talked to their children, the faster the children’s vocabularies grew and the higher the children’s I.Q. test scores were at age 3 and later. Since their research was published, there has been a push to encourage low-income parents to talk more to their children as a way to improve literacy.

“Reading takes you beyond the easy way to communicate,” said Dominic Massaro, psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “It takes you to another world and challenges you.”

But more picture book reading would be beneficial to children from every social class, Massaro said. What limits the tongue of even well-educated adults are “certain rules of discourse,” such as responding quickly, he said. That reduces word choices to those acquired early and used more frequently. In conversation, people also repeat words that have been recently spoken, further restricting the variety of words used.

Writing, on the other hand, is more formal, Massaro said, even in children’s books.

“Reading takes you beyond the easy way to communicate,” he said. “It takes you to another world and challenges you.”

Reading picture books to babies and toddlers is important, he said, because the earlier children acquire language, the more likely they are to master it.

“You are stretching them in vocabulary and grammar at an early age,” Massaro said. “You are preparing them to be expert language users, and indirectly you are going to facilitate their learning to read.”

Massaro said encouraging older children to sound out words and explaining what a word means if it isn’t clear in the context of the story will help build children’s vocabularies. Allowing children to pick the books they are interested in and turn the pages themselves keeps them active and engaged in learning, he said.

Reading to children also teaches them to listen, and “good listeners are going to be good readers,” Massaro said.

Massaro said that 95 percent of the time when adults are reading to children, the children are looking at the pictures, partly because picture books tend to have small or fancy fonts that are hard to read. If picture book publishers would use larger and simpler fonts, then children would be more likely to also focus on the words, helping them to become independent readers, he said.

In the study, Massaro compared the words in 112 popular picture books to adult-to-child conversations and adult-to-adult conversations. The picture books, which were recommended by librarians and chosen by him, included such favorites as “Goodnight Moon” and “If You Give a Mouse a Cookie.”

Most of the books Massaro used were fiction, but children’s picture books can also be nonfiction and discuss topics such as earthquakes or ocean life that would likely include a larger number of uncommon words, he said, giving them an even greater advantage over conversation.

To analyze the conversations, Massaro used two databases of words. One database involved 64 conversations with 32 mothers. The mothers had one conversation with their baby, age 2 to 5 months, while interacting with toys, and another “casual conversation” with an adult experimenter. The second database consisted of more than 2.5 million words spoken by parents, caregivers and experimenters in the presence of children with a mean age of 36 months.

In his comparison, Massaro identified the number of uncommon words, and he determined that the picture books he analyzed contained more of them than the language used in conversation.

Massaro’s study has been accepted for publication in The Journal of Literacy Research.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Comments (29)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

ROKIPEDIA 3 years ago3 years ago

To be honest your article is informative and very helpful. After i saw your site and i read it and it help me a lot. Thanks for share your kind information. You may like this post on https://rokipedia.net/how-to-improve-vocabulary-for-adults/

Margaret McKeown 5 years ago5 years ago

The issue should never be talking to vs reading to children, but interacting with children around language. Talk in a way that signals you expect a response; read as if in a conversation – comment, ask questions, talk about words in the book.

A well-known finding in the literacy field: interacting with children around books is more beneficial than simply reading aloud. See for example, Dickinson & Smith 1994; Teale & Martinez 1996; Beck & McKeown 2001)

Charris 5 years ago5 years ago

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326630284_The_impact_of_a_writing_programme_on_reading_acquisition_of_at-risk_first_grade_children here is a fantastic study for those looking for ways to help children gain better reading skills, especially if they are behind their peers. Thank you for this article. While I knew reading was important, I figured the quantity of words was important, not thinking about the quality. This has motivated me to set a 10 book minimum for my children with lots of uncommon words.

writingpaper 6 years ago6 years ago

Reading aloud is the best investment in the future of the child. The basis of literacy and interest in reading is laid in early childhood. Until the child learns to read independently, the influence of parents on his literacy is the most important. The number of home books, daily stories and regular visits to the library has a great influence on the development of the child's reading habits. My colleague conducted studies … Read More

Reading aloud is the best investment in the future of the child. The basis of literacy and interest in reading is laid in early childhood. Until the child learns to read independently, the influence of parents on his literacy is the most important. The number of home books, daily stories and regular visits to the library has a great influence on the development of the child’s reading habits. My colleague conducted studies show that at the age of three children from families where they read books, heard more than 20 million words than children from families where books are not read. If by the time of admission to school a child knows the letters well and has a certain lexicon, the level of his literary literacy remains high in the future.

Reading aloud is a more important factor in a child’s success in the future than the socioeconomic status of his parents.

Gigi 6 years ago6 years ago

Excellent article. Picture books are made for adults to read to children. That less frequent vocabulary found in picture book stories are the very words children probably do not know and will gloss over if the child is reading alone. The adult reading the story aloud to the child helps with unfamiliar vocabulary. This help provides the word knowledge children need to acquire to evetually add the word to his or her lexicon.

Cid and Mo 9 years ago9 years ago

We totally agree! When children listen to stories they not only hear a wide vocabulary but they are also exposed to complex sentence structures that are different from the ones used in conversations. Also, most importantly, children who hear stories will learn to enjoy books and are more likely to read for pleasure themselves! Success!

Cid and Mo

Tracey Needham 9 years ago9 years ago

This is such an important study. Parents in a lower social class often do not know what to talk to their children about which can also hinder the ability of the child to learn new vocabulary, however reading picture books gives a starting point for conversations. The story and pictures can promote discussion and further understanding. This study gives further evidence to the importance of reading to young babies and toddlers; each … Read More

This is such an important study. Parents in a lower social class often do not know what to talk to their children about which can also hinder the ability of the child to learn new vocabulary, however reading picture books gives a starting point for conversations. The story and pictures can promote discussion and further understanding.

This study gives further evidence to the importance of reading to young babies and toddlers; each new study is just adding further weight to the argument.

Anne 9 years ago9 years ago

Let's not put down alphabet books with realistic pictures of apples, balls, and so on. I recall reading such a book with my child who was not yet walking. I read what was written and added my own about the "crunch" when you bit into an apple and more. There was a large "A" and "a" on the page. My child then pointed to the letters and clearly wanted … Read More

Let’s not put down alphabet books with realistic pictures of apples, balls, and so on. I recall reading such a book with my child who was not yet walking. I read what was written and added my own about the “crunch” when you bit into an apple and more. There was a large “A” and “a” on the page. My child then pointed to the letters and clearly wanted to know more about them as if why aren’t you talking about these. Phonics began that day… No one taught my son to read though sometimes he emphasized the wrong syllable in foreign names from the newspaper. I am blessed.

Concerned Parent Reporter 9 years ago9 years ago

I believe the money paid,to do,the study was money waisted. Of course all people soak,up info. Better when road to for thousands and thousands of common sense reasons. 1. Some do not speakmenglishmwell and itmismtoughmtomstumble and stumble over words one can't pronouncemandmthis creates a lack of flow,ofmcomprehensionmet. 2. In our electronicmtextmworld, many are in a hurry and rush reading, skimming,mane comprehension is,lessened as compared to those who rest while being read to. 3. there is a … Read More

I believe the money paid,to do,the study was money waisted.

Of course all people soak,up info. Better when road to for thousands and thousands of common sense reasons.

1. Some do not speakmenglishmwell and itmismtoughmtomstumble and stumble over words one can’t pronouncemandmthis creates a lack of flow,ofmcomprehensionmet.

2. In our electronicmtextmworld, many are in a hurry and rush reading, skimming,mane comprehension is,lessened as compared to those who rest while being read to.

3. there is a magesty,of,theatre in hearing someone read ,in person, that is a God effect and captivates people to understand in more depth , not unlike eye contact.

stupid study, and notmworthmthemarticle

AutismMom 9 years ago9 years ago

When my daughter was two years old, she was diagnosed with a developmental disability and was not talking and not understanding us. I would check out loads of children's picture books from the library to read to her. The pictures weren't enough for her to understand, so we would take stuffed animals and act out what was happening on each page. . We would read and act out about 13 books every evening before bed--plus … Read More

When my daughter was two years old, she was diagnosed with a developmental disability and was not talking and not understanding us. I would check out loads of children’s picture books from the library to read to her. The pictures weren’t enough for her to understand, so we would take stuffed animals and act out what was happening on each page. . We would read and act out about 13 books every evening before bed–plus some books during the day. (She also had other interventions to help her learn to talk). The repetition of familiar books was very helpful. We would always do the same book twice in a row before moving on to another book. Fred and Ted (Big Dog, Little Dog) books were the best. She got to the point where she not only understood them and could act them out, she could flip the language (Book says: Ted liked beets” she could take her stuffed animal and have it pretend to say, “I like beets.” Years later, she is communicating on grade level and is about a year ahead of her age group in reading. The repetition, pictures, and predictability of children’s books make them ideal for helping kids learn–not just literacy but also about the world and how to communicate verbally.

Replies

Parent 9 years ago9 years ago

What a wonderful post. I sure wish that some non profit would do some valuable study on what you presented here to see if the act of reading that way did propel an autistic child forward more or not. A study is in order. . . . I ask you consider writing to some non profit that focuses on autism and ask if you can help shape a study to test out what you were doing … Read More

What a wonderful post. I sure wish that some non profit would do some valuable study on what you presented here to see if the act of reading that way did propel an autistic child forward more or not. A study is in order.

.

.

.

I ask you consider writing to some non profit that focuses on autism and ask if you can help shape a study to test out what you were doing with your child and to educate others if it works or not in a validated study.

.

.

.

Please consider that.

.

.

.

Parent

Susan Frey 9 years ago9 years ago

Thanks for your comment. I forwarded it to Professor Massaro, who is more in touch with the research community. I simply report on studies that I see. I don’t conduct them. It sounds like a terrific idea.

Dom Massaro 9 years ago9 years ago

Thanks much for sharing your success story with your child.

I would suggest contacting Autism Speaks (https://www.autismspeaks.org/) about

your experiences.

Parent News Opinion 9 years ago9 years ago

How about facial ting more with parent, and , ask parent if someone from autism speaks can call her.

Parents often work two jobs and large non profits and others need to better reach out to facilitate in stronger ways.

Parent News Opinion 9 years ago9 years ago

I meant to write

how about facilitating more with parent

Eileen 9 years ago9 years ago

While I see NO downside to reading aloud to/from any age group, I also want to state that the right type of verbal discussion can be as valuable or more valuable depending upon the topic. I cannot begin to explain all that I learned listening to adult conversations at the dinner table. Controversial current event topics began to make sense. I certainly learned my parents' preferences regarding the world order. Civics … Read More

While I see NO downside to reading aloud to/from any age group, I also want to state that the right type of verbal discussion can be as valuable or more valuable depending upon the topic. I cannot begin to explain all that I learned listening to adult conversations at the dinner table. Controversial current event topics began to make sense. I certainly learned my parents’ preferences regarding the world order. Civics was stressed beyond most measures of exposure in school. What has happened to the informed conversation? Obviously, the listener/learner will hear many biased opinions, however, the defense of those opinions can be a very valuable learning experience too.

Frances O'Neill Zimmerman 9 years ago9 years ago

Studies are always interesting, but do we really want to set up a dichotomy between talking to kids vs. reading aloud to them? First off, I have to say how important it is to limit screens-time if you want to enhance a kid's love of reading. Obviously, both talking and reading aloud are important for both a child's sense of well-being and becoming literate. One aspect of reading aloud to young children that is sometimes … Read More

Studies are always interesting, but do we really want to set up a dichotomy between talking to kids vs. reading aloud to them? First off, I have to say how important it is to limit screens-time if you want to enhance a kid’s love of reading.

Obviously, both talking and reading aloud are important for both a child’s sense of well-being and becoming literate. One aspect of reading aloud to young children that is sometimes overlooked is taking time to encourage the youngster’s comments on the story or the illustrations — what feelings does the story elicit, predictions about what might happen, counting numbers, naming animals, identifying colors, appreciating the illustrations and wondering how they were made.

Also, there’s no age limit to the mutual pleasure of reading aloud or being read to. I know teenagers who will accept a grandparent’s offer to read aloud at bedtime and I know adults who do read-alouds on road-trips. Reading aloud is a human interaction and people remember the sound of a reader’s voice –a teacher, parent, grandparent, older brother, a friend, forever. One of life’s joys is discussing literature with someone who’s read what you’ve read, or who tells you about a book that’s unknown to you — and that someone can be a little kid or another adult.

Bill Jenkins 9 years ago9 years ago

Our brains are designed to pay attention to the novel and gloss over the familiar. This goes all the way back to basic survival awareness where the unexpected and new are either threats or opportunities, but it can be harnessed for learning and complex cognitive processing. Combining that with the power of storytelling and its ability to touch our thoughts and emotions at the same time and you have a powerful teaching tool. … Read More

Our brains are designed to pay attention to the novel and gloss over the familiar. This goes all the way back to basic survival awareness where the unexpected and new are either threats or opportunities, but it can be harnessed for learning and complex cognitive processing. Combining that with the power of storytelling and its ability to touch our thoughts and emotions at the same time and you have a powerful teaching tool. Being exposed to novel words in a familiar and stimulating context is important to a child’s brain development and learning ability. Conditioning them that not everything is familiar will serve to keep them on their toes and alert for new stimuli, terms, and concepts. Their internal reward is the feeling of accomplishment and approval that comes with learning something new — aspiring and achieving. Stimulation is vital to the health of our brains, especially children’s brains. Attaching the learning moment to an emotion (preferably a positive one such as joy, excitement, or delight) solidifies the memory as significant and aids in placing it in long-term storage. Let’s not squander a mind that is open to the world by boring it into a stupor.

Mdw 9 years ago9 years ago

At what age do the benefits of reading aloud begin to taper off? I’m still reading aloud to my 8 year old, does it continue thru the tween years? Any studies done on that?

Replies

Dom Massaro 9 years ago9 years ago

There is no reason to stop reading to your child if you both are enjoying it. More importantly, the finding that the earlier you learn a word the better you master it holds well into adulthood. A particularly positive influence would occur if your shared reading stretches your child’s vocabulary beyond what he or she would normally read alone.

Dom Massaro

Shannon 9 years ago9 years ago

I loved reading this article. I am a veteran teacher, starting my 27th year, and have been reading aloud to students (no matter what grade level I taught…6th graders seemed to love it more than most other grade levels ironically) . How can I convey this to my parents or colleagues how vital this is for our children?

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

Mdw: I'm not familiar with studies indicating increased reading comprehension (measured) via being read to aloud for older students. I will say, from experience, that students through 9th grade seem to appreciate it. Certainly junior high kids do, caught as they are in that "tweener" stage. Reading aloud, if done well, can allow a teacher to provide access to more sophisticated reading materials than student's current reading fluency levels might otherwise allow. Though a reading disability … Read More

Mdw:

I’m not familiar with studies indicating increased reading comprehension (measured) via being read to aloud for older students. I will say, from experience, that students through 9th grade seem to appreciate it. Certainly junior high kids do, caught as they are in that “tweener” stage. Reading aloud, if done well, can allow a teacher to provide access to more sophisticated reading materials than student’s current reading fluency levels might otherwise allow. Though a reading disability or lack of experience with English might not allow students to tackle more difficult text materials, they can frequently work with more sophisticated ideas. Which, in the long run, typically adds to comprehension levels as it develops increased context. Other similar strategies, readers’ theater, choral reading, and “jig-sawing” can also work well in the classroom.

Don 9 years ago9 years ago

I guess it depends because at some point you may be reading to your child in lieu of your child reading alone. If your child wants you to read past the age when s/he should be reading alone then it is becoming a crutch.

FloydThursby1941 9 years ago9 years ago

I think reading with your kids makes it fun and teachers them it’s important. They associate fun time with parents and approval with being able to read. 60% of Asians teach their kids to read before Kindergarten vs. 16% of whites, the main cause of the gap between these two groups in California. Reading is always better than talking.

Luis Carbajal 9 years ago9 years ago

You are absolutely right Floyd. Reading to children is as much a pleasurable bonding experience as it is a learning experience.

If a child or any human being for that matter, associates an activity with pleasure, he will be more likely to continue doing it.

Children enjoy being with their parents and doing something that is intimate. Reading is one of those activities.

Karen Mitcham 9 years ago9 years ago

Great article So true!

Jamie Hogan 9 years ago9 years ago

As both a mom and illustrator of picture books this Is concrete validation of not only the word wealth but also visual literacy benefits of a child and a story in your lap. Amen!

Don 9 years ago9 years ago

There's some very conflicting ideas in this article concerning reading more and talking more. Massaro says, "....encouraging parents to talk more to their children to increase their vocabularies – has its drawbacks." Frey goes on in the next paragraph too cite Hart and Risley who "concluded that the more parents talked to their children, the faster the children’s vocabularies grew and the higher the children’s I.Q. test scores were at age 3..." Is the author … Read More

There’s some very conflicting ideas in this article concerning reading more and talking more. Massaro says, “….encouraging parents to talk more to their children to increase their vocabularies – has its drawbacks.” Frey goes on in the next paragraph too cite Hart and Risley who “concluded that the more parents talked to their children, the faster the children’s vocabularies grew and the higher the children’s I.Q. test scores were at age 3…” Is the author conflating reading and talking (conversation)? Then there’s some explicit advice given by Massaro for everyone to read more, which is fine except for the fact that it is couched in the notion that doing so, ” would not only expose them to more words, he said, but it also would have a leveling effect for families with less education and a more limited vocabulary.” This totally omits what is being read and what is being discussed as factors. Which brings me to the next point.

The theory espoused here is that Moby Dick is better than The Old Man and the Sea – that reading is more like the first and talking is more like the second. I can imagine these researchers with their abacuses counting the words and separating them into big and small. There’s no discussion of storyline, character development, motif, meaning, etc. It’s all about some quantitative word uptake. Here’s a excerpt of a Carol Burris article about Common Core and the opt out movement:

“Here is a sample from the Grade 6 Reading test that was given in Virginia last year to measure the state’s Standards of Learning (SOL):

“Julia raced down the hallway, sliding the last few feet to her next class. The bell had already rung, so she slipped through the door and quickly sat down, hoping the teacher would not notice.

Mr. Malone turned from the piano and said, “Julia, I’m happy you could join us.” He continued teaching, explaining the new music they were preparing to learn. Julia relaxed, thinking Mr. Malone would let another tardy slide by. Unfortunately, she realized at the end of class that she was incorrect.”

That is certainly a reasonable passage to expect sixth-graders to read. You can find the complete passage and other released items from the Virginia tests here.

Contrast the above with a paragraph from a passage on the sixth-grade New York Common Core test given this spring.

The artist focuses on the ephemerality of his subject. “It’s there for a brief moment and the clouds fall apart,” he says. Since clouds are something that people tend to have strong connections to, there are a lot of preconceived notions and emotions tied to them. For him though, his work presents “a transitory moment of presence in a distinct location.” End

In the first passage there’s a tangible meaning and interaction relative to the child doing the reading. The second passage is abstract and evocative, and clearly beyond the average 6th grade mentality. But, gee whiz, its got a lot of big words. Well , no need to go off topic and trash Common Core. It does a pretty good job of trashing itself or as Burris noted – “I will let readers draw their own conclusions.”

“You are stretching them in vocabulary and grammar at an early age,” Massaro said. “You are preparing them to be expert language users, and indirectly you are going to facilitate their learning to read.”

Massaro wants to teach his 36 month old toddler grammar. I read to my kids so they would love a good story and develop an appreciation for writing and the aspirations of humanity. (drum roll)

The stuff of this article comes straight out of the Common Core slice and dice playbook which is not surprising given the big money donated by Gates to Ed Source.

As its main author, David Coleman said about writing in school, “They ( society/employers) don’t give a sh*t what you think or what you feel.” Maybe his mother talked too much and read too little.

Replies

Dana 5 years ago5 years ago

Reading aloud is the best investment in the future of the child