Assembly Republicans announced bills Wednesday that would change state laws that establish teacher tenure and a layoff system based on seniority – two employment protections for teachers that a California Superior Court judge threw out in his sweeping Vergara v. the State of California ruling last year. (Updated with correction below).

The legislation was among a suite of bills that the 28-member Republican caucus announced. Included is a bill to strengthen the law on teacher evaluations, which hasn’t been changed in four decades, and one to eliminate a cap on school district budget reserves that has angered school education groups. Another bill requires school districts to provide more details on spending in their annual budget accountability plans, the Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs) that the State Board of Education requires. Civil rights groups also have called for more budget transparency.

As defendants in the lawsuit brought by the nonprofit Students Matter on behalf of nine students, the state and California’s two teachers unions have filed an appeal of Judge Rolf Treu’s Vergara decision. Treu ruled that five employment laws violated the rights of poor and minority children, saddling them with the state’s worst-performing teachers. An appeals court ruling probably won’t happen until 2016 at the earliest. Democrats, who control the Legislature, at this point are watching the appeals process play out before deciding whether to change laws.

Republicans, however, said there is no reason for delay.

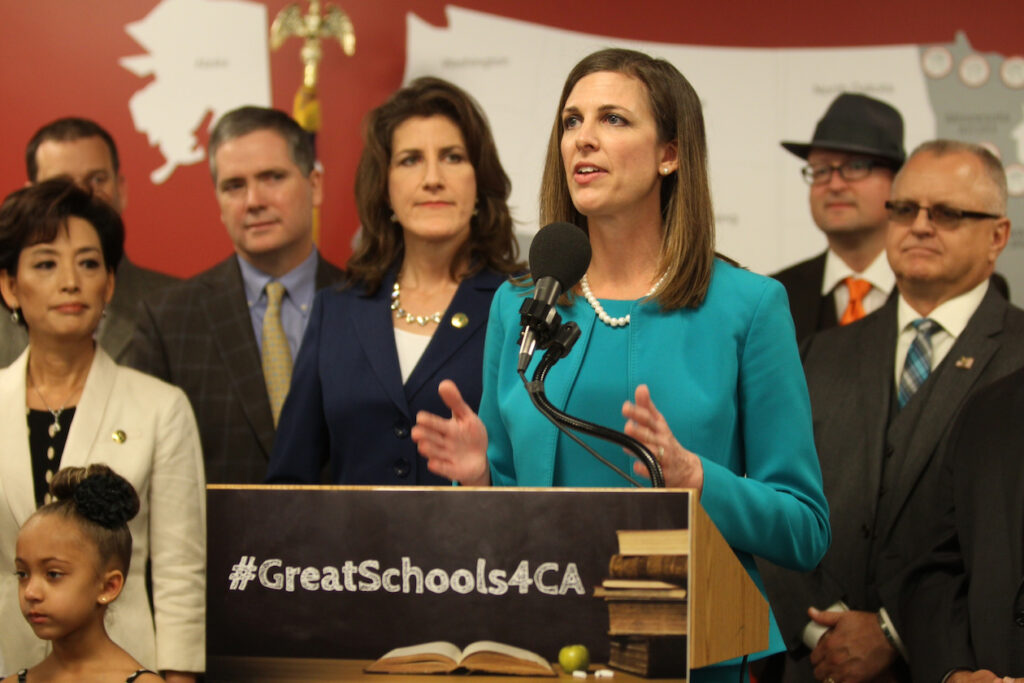

“We have seen throughout history that cases can take years to resolve in courts,” Kristin Olsen, Assembly Republican leader, said in an interview. “Systemic problems have been failing kids for years. We need to take action now and hope Democrats will become partners.”

Assembly Bill 1248, introduced by Assemblyman Rocky Chavez, R-Oceanside, would extend the probationary period from two years to three before awarding tenure, which grants legal protections to new teachers. In addition, a teacher would need positive evaluations in each of those years in order to be considered for tenure. A teacher deemed to be ineffective in two consecutive annual evaluations would lose tenure status and once again be placed under probation.** Chavez’s bill presumes there would be other changes to the current teacher evaluation law, which are specified in AB 1078.

AB 1078, by Assemblywoman Kristin Olsen, R-Modesto, would update the 40-year-old law on teacher evaluations, the Stull Act, parts of which, Olsen noted, “school districts have largely ignored.” The Stull Act requires evaluations every other year for most tenured teachers and every five years for teachers with 10 or more years of experience. It’s currently a pass-fail system, with teachers branded either effective or ineffective.

Olsen’s bill requires annual evaluations for all teachers and introduces four evaluation categories focused on improvement: highly effective, effective, minimally effective and ineffective. It requires the State Board of Education to update the guidelines for teacher evaluations under the Stull Act by July 1, 2016 and encourage districts to include student surveys and peer evaluations as part of the process.

The Stull Act requires that student performance, including scores on state standardized tests, be a component of a teacher’s evaluation. However, teachers unions have opposed linking test scores to an evaluation, and, according to Olsen, most districts don’t comply with the law. In 2012, in response to a lawsuit brought by the nonprofit advocacy group EdVoice, a Superior Court judge ordered Los Angeles Unified to include measures of student performance in evaluations, although the decision applied only to that district.

AB 1078 also addresses the issue of compliance with the Stull Act. It would prevent the state board from granting any waiver from the Education Code to a district that fails to use test scores and other measures of student performance. Districts often seek waivers of various sorts from the board.

Olsen said this year’s version is “more modest” than her previous bills on teacher evaluations, which never made it out of the Assembly Education Committee. Compared with previous bills, AB 1078 gives districts more discretion in determining elements of an evaluation, and it does not specify what percentage of an evaluation test scores and other student performance measures must comprise, she said.

AB 1044, by first-term Assemblywoman Catharine Baker, R-Dublin, would repeal the “last-in-first-out” statute that requires all teacher layoffs to be based on seniority. Districts would negotiate new criteria with their teachers unions. Seniority could still be one factor, but the bill would require that a “significant” component be based on a teacher’s “evaluation rating.” Districts could make exceptions for special cases, such as teachers in high-need subjects or with special training; the current law already permits this.

AB 1226, by Chavez and Assemblyman Eric Linder of Corona, would require school districts to describe their plans for teacher training, including setting specific goals and committing money for them, as part of their LCAPs that they update annually. State law has set eight priorities that districts must account for in their LCAPs; professional development would become the ninth. If they persuade Democrats to vote for the bill, Chavez and Linder still face a possible veto from Gov. Jerry Brown, who has opposed any changes so far to the LCAP law.

AB 1099, also by Olsen, would likely also be opposed by Brown if the bill reaches his desk. It would require LCAPs to include a detailed accounting of all district expenses as well as spending at the school level, along with a breakdown of extra money allotted under the new spending formula to low-income students, children learning English and foster children. The state board resisted doing what Olsen calls for when creating regulations for LCAPs last year, saying that it wanted to give districts latitude in spending.

Olsen said her bill is consistent with Brown’s position that spending under the new formula should be transparent for parents and the community. She agrees with the governor that school boards need flexibility to determine how the money will be used.

The bill also requires districts to publish an explanation of how they evaluate teachers and principals and list the aggregate number of teachers receiving satisfactory and unsatisfactory evaluations, by school.

As part of the state budget, legislators last year passed a limit on how much money districts could put aside for potential fiscal emergencies. The cap limits districts’ reserves to between 3 percent for Los Angeles Unified and 10 percent for tiny districts in the year after the state put any amount of money into a newly established education rainy day fund. Although the Legislative Analyst’s Office says that would occur infrequently, the California School Boards Association said the cap would jeopardize districts’ financial stability and violated the principle of local control over spending decisions. AB 1048, authored by Baker and Assemblyman David Hadley, R-Manhattan Beach, would repeal the cap. Sen. Jean Fuller, R-Bakersfield, has introduced a similar bill, Senate Bill 774.

**Correction: An earlier version state incorrectly that a teacher identified as ineffective in two consecutive evaluations would be dismissed. That teacher would be placed under probation, without tenure protections.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.