Source: The Invisible Achievement Gap Report

Source: The Invisible Achievement Gap ReportFoster youth perform worse in school depending on where they are placed, such as group homes, and how long they stay there, according to a new report that reveals the impact of living conditions and other factors on the academic achievement of foster children.

The Invisible Achievement Gap, Part 2 follows an earlier report that detailed the dismal academic achievement of California’s 43,000 school-aged foster youth.

In the latest report, the researchers found that older foster students – particularly those who live in group homes or have experienced three or more foster placements in one school year – have the lowest academic achievement of all foster youth.

Together, the two reports break new ground because, as the authors note, little has been known about the education of youth in foster care “despite the state’s legal responsibility for these children.”

Part 2 was released Thursday by the Center for the Future of Teaching and Learning at WestEd, a research organization based in San Francisco, and the California Child Welfare Indicators Project, a data collaboration enterprise between University of California, Berkeley and the California Department of Social Services.

The report is “an invaluable tool” for school districts as they develop plans to improve the academic achievement of foster youth, said Jesse Hahnel, director of the National Center for Youth Law’s Foster Youth Education Initiative.

About a third of foster students are placed in homes certified by private foster agencies, according to the report. Close to one-third live with relatives. Among the remaining students in foster care, 15 percent are with legal guardians, 10 percent are in group homes and 8 percent are in state-licensed foster homes.

Relying on data from the 2009-10 school year, the report found that two-thirds of students living in group homes scored below basic or far below basic on the state’s STAR math tests, and 61 percent scored that low in English language arts.

In addition, the researchers found that half of students who experienced three or more foster placements in one school year scored in those bottom two levels in English, and 44 percent scored that low in math.

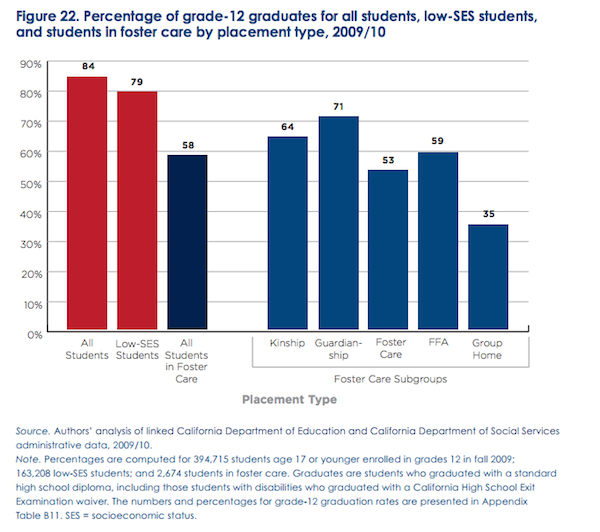

Graduation rates for high school seniors in foster care were also dismal, with only 35 percent of those living in group homes graduating, compared to 79 percent of other low-income seniors, according to the report. High school seniors who were living with relatives or with guardians were the most likely to graduate, but they still lagged behind students not in foster care. (See the graph.)

Foster youth are more likely to be diagnosed with a learning disability. (Click to enlarge) Source: The Invisible Achievement Gap, part 2

The researchers also found that:

- Only two-thirds of students in foster care – and only half of group home students – stayed in one school for the entire school year, compared with 90 percent of other low-income students.

- Foster students are more likely to be diagnosed with a disability – particularly boys, older students, group home students, and students who have been in foster care for three or more years.

The report lays the blame for the general lack of knowledge about academic outcomes for foster youth on a lack of collaboration between the education and child welfare systems.

The two systems do not have a shared definition of who is a foster child or unique student identifiers so foster students’ academic progress can be tracked.

“As a result, the education needs of these students have been unstudied and unrecognized – possibly leaving many already vulnerable students in foster care trailing behind their classmates in academic achievement,” the report states.

But things are about to change. The state will soon be sending districts lists of the names of their foster students. Districts are then required to create a Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) to target resources to foster youth and monitor their progress.

Hahnel says districts should use the data in the new report to help them target extra resources to the most vulnerable foster students.

“All foster children need services, but let’s pay particular attention to youth living in group homes,” he said. “In terms of prioritizing summer school or tutoring, districts need to make sure that youth in group homes are accessing those services.”

Child welfare agencies should also take note, Hahnel said.

Although social workers generally see group homes as placements of last resort, the report is further evidence “that these are poor choices for children,” he said.

In addition, state policymakers need to recognize that foster children living with relatives are also struggling academically, Hahnel said. Under current law, the state Foster Youth Services program is not allowed to support them.

“This report makes it clear that needs to change,” he said.

Susan Frey covers expanded learning time. Contact her at sfrey@edsource.org. Sign up here for a no-cost online subscription to EdSource Today for reports from the largest education reporting team in California.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.