Gov. Jerry Brown’s plan to immediately start paying off the $74 billion shortfall in funding for teacher pensions was, for school districts that would bear the brunt, the big May budget surprise. On Thursday, two key lawmakers responded to districts’ calls for total relief next year by urging legislators to meet them halfway.

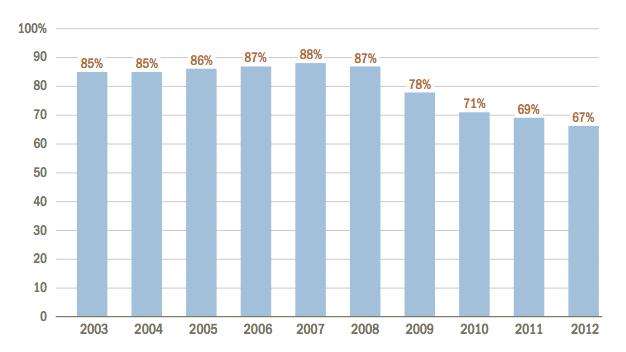

CalSTRS’ defined benefit plan for teachers and administrators, now two-thirds funded, would reach 70 percent of funding in 2024 and full funding in 2046, under Gov. Brown’s plan. Source: CalSTRS.

Assemblyman Rob Bonta, D-Oakland, and Sen. Norma Torres, D-Pomona, who chair committees looking into the pension issue, endorsed an alternative payment plan proposed by the California State Teachers Retirement System. Instead of paying $350 million to CalSTRS in 2014-15, which is the increased amount Brown proposed, school districts would pay half that. They would make up the difference with higher payments in future years. The alternative plan would leave intact the key elements of Brown’s plan to eliminate CalSTRS’ deficit, which he outlined in the revised state budget.

During a two-hour hearing in Sacramento, education groups generally praised Brown’s overall division of responsibility among school districts, teachers and the state for making the CalSTRS pension program for teachers and administrators whole at the end of 30 years. But they said that the plan to start phasing it in on July 1 caught them unaware just when they were completing the planning process under the state’s new Local Control Funding Formula. In January, Brown had suggested higher payments would begin in 2015-16; districts built their budgets around those assumptions, representatives said.

Brown’s plan would be a $35 million hit on the budget, Leilani Aguinaldo Yee, the deputy director of government relations at Los Angeles Unified, testified. As the new funding law requires, she said the district has drafted a “robust” planning document, the Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP), after meeting with parents and community groups.

“So now, as of 10 days ago, we have to go back to the same individuals and say a significant amount is off the table,” Yee said.

Brian Rivas, director of policy and government relations for The Education Trust-West, a nonprofit advocacy group, seconded the worry that diverting money so late in the process of writing the LCAP would “jeopardize trust between communities and districts.”

“Trust is very fragile,” he said.

Investment income to CalSTRS, in green, plummeted in 2008-09. Though rebounding since, loss in assumed income created a $74 billion shortfall in assets needed to meet projected retirement payments over the next 30 years. Contributions from teachers and administrators, the state and school districts into the system, in red, meanwhile remained constant. Source: CalSTRS.

Brown has proposed increasing spending for districts by $4.5 billion; $350 million more in CalSTRS payments would consume 8 percent of the total. The ratio would rise as higher contribution rates are phased in, diverting more money that would have been available for the classroom under the Local Control Funding Formula.

Jeff Vaca, deputy executive director of governmental relations for the California Association of School Business Officials, was among those who called for either a one-year delay or a corresponding increase in district funding to meet the higher CalSTRS costs for districts.

There are other alternatives, several people testified. Since the Legislative Analyst’s Office is predicting the state would take in as much as $2.7 billion more in funding for K-12 schools and community colleges than Brown’s budget projects, they said that some of that money could be a down payment for meeting CalSTRS’ obligations.

CalSTRS’ defined benefit program for its 860,000 members is funded through contributions from the state, employers (school districts) and employees, with contributions determined as a percentage of employees’ pay.

CalSTRS lost about 40 percent of the value of its investments in 2008 in the stock market freefall. As a result, the pension program is only about two-thirds funded to meet projected pension payouts over the next 30 years. If nothing were done, it would run out of money in 2046, according to CalSTRS.

Under Brown’s plan, total annual contributions would increase by about $5 billion per year, to $10.5 billion, divided in the following ways:

- Districts would shoulder about $3.7 billion of the increase, with their share more than doubling, from 8.25 percent of payroll to 19.1 percent. The increases would be fully phased in over seven years, and that wouldn’t change under CalSTRS’ alternative, but would just be shifted – less in the first three years, more in the last four years.

- Teachers’ and administrators’ contributions would rise from 8 percent to 10.25 percent, phased in over three years. Court rulings have limited the Legislature’s ability to raise employees’ rates, and the 10.25 percent would be the maximum, short of challenging court rulings.

- The state’s share, now 3 percent, would rise to 6.3 percent, also over three years. That would increase the state’s costs from $1.4 billion this year to $2.4 billion – money that would come from the General Fund, not the state’s share of funding for schools, Proposition 98.

“We’re appreciative of that,” said Estelle Lemieux, a lobbyist for the California Teachers Association, which endorsed Brown’s plan. “The state is willing to contribute more than we thought it would.”

Wiping out the $74 billion deficit, bringing CalSTRS to full funding in 30 years, would require $237 billion in total increased contributions. Districts would bear about two-thirds of the total, employees about one-tenth and the state about a quarter.

John Fensterwald covers education policy. Contact him at jfensterwald@

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.