A coalition of school districts wants Gov. Jerry Brown and the Legislature to clarify how much money will be available to schools following the deal that legislators struck earlier this year requiring districts to make higher pension payments.

The coalition isn’t asking for the state to pick up a bigger share of the expense, recognizing that won’t happen. Instead, it wants the Legislature to distinguish retirement costs that districts must pay from the rest of the general funding that districts receive under Proposition 98, the formula that determines how much money K-12 schools are entitled to. The effect would be to shrink the amount that districts get from the Local Control Funding Formula while sending a clear message to temper the public’s and staff’s expectations: There’d be more money to go around, were it not for escalating retirement expenses.

“We are seeking a different funding method to deal with the extraordinary cost to bring security to the retirements of school employees and to bring transparency” to the Local Control Funding Formula, board members of the CalSTRS Funding Coalition wrote in an article last week announcing its formation. It was published on the website of California School Services, a school consulting and lobbying firm that said it supports the new effort. The four-district coalition, which expects to grow, includes Los Angeles Unified, the state’s largest school district.

Credit: John C. Osborn/EdSource Today

All three contributors to retirement benefits for teachers – teachers themselves, the state and school districts – will pay more under the legislation approved this year. Districts will absorb 70 percent of the increase, rising from several hundred million dollars this year to nearly $3.7 billion annually in 2020-21.

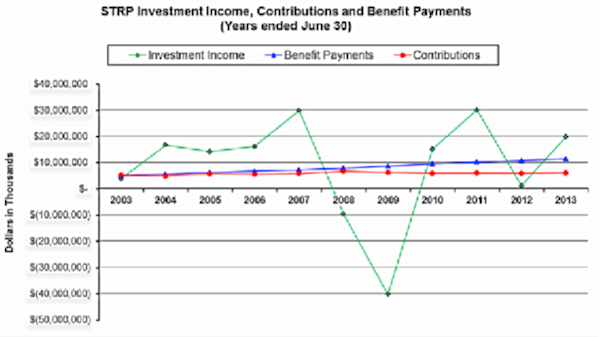

In June, Brown proposed and the Legislature adopted substantial increases in contributions to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System. Teachers, the state and districts will pay increasing amounts over seven years. The higher rates will bring the pension program to full funding in 30 years, wiping out a $74 billion deficit caused by plummeting stock values and investment returns in the 2008 recession.

Total annual contributions will double by 2020-21 and then continue, with school districts bearing about 70 percent of the $5.2 billion increase. The coalition said that CalSTRS costs will rise from 3.8 percent of an average district’s budget to 9 percent over that time. That increase will cut into money the Legislature anticipated districts would spend as funding was restored to pre-recession levels. Under the new funding formula, districts are also planning to spend more as they expand programs for “high-needs” students, including low-income students and English learners.

The state’s share of pension costs, though smaller, will also double, and teachers’ contributions, deducted from their paychecks, will rise by about a quarter, from 8 percent of their pay to 10.25 percent.

The coalition is asking that districts’ retirement charges be a separate account within Proposition 98. Districts currently have to make room for retirement costs within the Local Control Funding Formula. Since retirement costs aren’t discretionary, they shouldn’t be part of the formula, the coalition argues.

“If it had been a one-time increase, we would be fine, but it will continue to grow for six more years,” said Scott Siegel, superintendent of Ceres Unified.

When it passed the new funding system in June 2013, the Legislature set the goal of restoring funding for all districts to 2007-08 levels within seven years while providing additional money for high-needs students. But that was a year before lawmakers passed the plan for rescuing the CalSTRS retirement plan. Setting money aside for CalSTRS obligations would delay reaching the funding goal, though the coalition didn’t estimate by how long.

The point, said Scott Patterson, deputy superintendent of business services for the Grossmont Union High School District and a coalition board member, would be “communicating to parents and staff that the state is not going to reach the target of getting back to 2007-08 levels as soon as they would like to.”

“For all stakeholder groups, there’d be a clear picture of new money coming to districts – how much parents can expect for targeted funds for students and how much is available for teachers to negotiate pay and benefits,” said Scott Siegel, superintendent of Ceres Unified School District. For his 12,000-student district, higher CalSTRS expenses will cost an additional $1 million annually out of a $100 million budget.

“If it had been a one-time increase, we would be fine, but it will continue to grow for six more years,” he said.

Desert Sands Unified is also part of the coalition, along with Los Angeles Unified, Ceres and Grossmont. Patterson said he expects the coalition to grow to 150 to 200 districts – whichever are willing to underwrite the lobbying effort. He said that the coalition has not yet presented its idea to officials from the Department of Finance, which prepares Brown’s budget, or to legislative leaders.

“I can’t think of why a district would not be in favor of this,” Patterson said.

H.D. Palmer, spokesman for the Department of Finance, declined to comment on the proposal, pending the release of Brown’s proposed state budget in January.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.