The U.S. Department of Education said Tuesday that California special education programs need federal intervention, citing the lack of significant academic progress for students with special needs. California is one of three states, along with Texas and Delaware, designated for a one-year program of intervention.

The designation comes as U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan announced a new accountability system aimed at strongly encouraging states to provide research-proven academic interventions so that children with learning disabilities or speech and language impairments – the vast majority of students in special education – and students with other special needs can excel.

“This is a significant and frankly long-overdue raising of the bar in special education,” Duncan said in a telephone press briefing. The federal intervention will increase monitoring and oversight to ensure the state is meeting the new accountability standards.

Using a new framework called Results-Driven Accountability, the department for the first time is holding states accountable for test scores and other performance indicators for students with special needs. In California, test scores for students with disabilities are generally the lowest of any subgroup. Duncan called the push to include academic measures “a major shift” in how the federal government oversees special education.

If student test scores hadn’t been included in federal evaluations this year, California would have been in compliance under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which in prior years was primarily determined by whether states had met procedural requirements for students with special needs, such as timelines for assessments and filing complaints. “Basic compliance does not transform student lives,” Duncan said.

“This is a significant and frankly long-overdue raising of the bar in special education,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

California was cited for federal intervention based on factors that included the proficiency gap between children with disabilities and all children on statewide assessments and the poor performance of children with disabilities on the National Assessment of Educational Progress test, the Education Department said in a letter to State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson.

In a statement, the California Department of Education said, “Like other states, we are concerned that the categorization is more the result of the particular methodology used than of the actual performance of the state’s school districts.” The department added that it will be working with the U.S. Department of Education to resolve issues.

The Education Department also said the California Health and Human Services Agency’s Department of Developmental Services will receive four years of federal intervention to improve the early identification of infants and toddlers with disabilities and enhance programs to assist young children in meeting developmental goals.

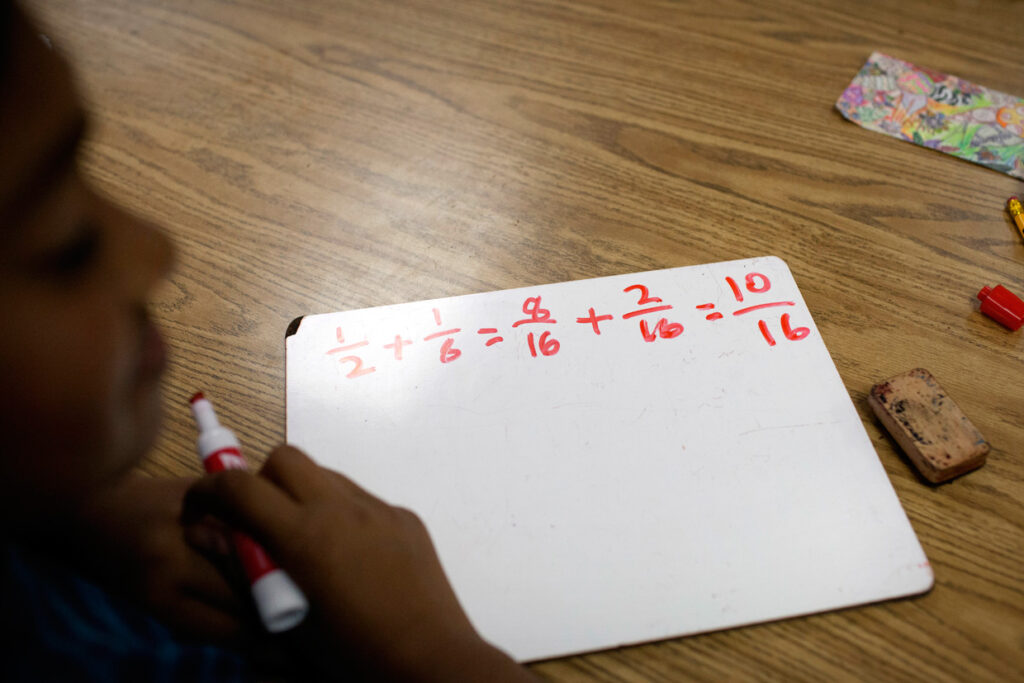

To help states improve outcomes for students with special needs, Duncan announced the creation of a $50 million technical-assistance center. The center will help increase the use of evidence-based practices for teaching reading, math and other subjects to students with a range of learning, physical and emotional disabilities. The description of the new center cites a wide range of obstacles to improving academic achievement for students with special needs, including a lack of coordination between state special education and general education systems. In one example, general education school improvement teams meet to discuss how to improve outcomes for students with disabilities, but special education staff are not included in the meetings nor consulted about effective strategies.

Through the Statewide Special Education Task Force, California is already undergoing a review of how to transform special education in the state, including possible changes in credentialing requirements for general education and special education teachers.

Vicki Barber, co-executive director of the task force, applauded the federal government’s new emphasis on achievement outcomes for students with special needs. And she agreed with the need to closely intertwine special education services with general education teaching. “If you’re going to change special education, you’ve got to change general education,” Barber said.

In California and nationwide, the majority of students identified for special education services have mild to moderate disabilities, she said. “They should be served in a general education setting,” Barber said. “That general education teacher would say ‘I don’t know how to teach students who have processing difficulties,’ so we’ve got to give them a better tool set.”

She added that increasing the training of general education teachers in research-based interventions for teaching reading, a critical skill, will benefit all struggling readers, not just students identified as having special needs.

At the same time, special education teachers often lack the deep subject knowledge of the classroom teacher, making it difficult for students who spend much of their day in separate special-education classrooms to learn the reading, writing, mathematics, science and history content they will need to succeed on tests and beyond, she said.

“All the research is very clear that kids who have exposure to a robust general education curriculum will do better,” Barber said. The task force, created by the State Board of Education, is expected to release draft recommendations by the end of November.

To explain why the new federal accountability framework is pushing academic achievement for children with special needs, Duncan and three other top educators took pains on Tuesday to describe exactly who “special education” students are.

The educators – Duncan, Massachusetts Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell Chester, Tennessee Education Commissioner Kevin Huffman and Acting Assistant Secretary for Special Education and Rehabilitative Services Michael Yudin – said that the majority of students in special education should be achieving the same test results as students in general education.

“I want to stress that the vast majority of students with disabilities do not have significant cognitive disabilities,” Duncan said. For example, in Tennessee, more than 40 percent of students receiving special education services have a learning disability such as dyslexia and another 40 percent have a speech or language disorder, such as stuttering.

“The majority are students who are perfectly capable of learning and doing better,” Huffman said.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.