The conventional wisdom that American students lag far behind top performers like Finland and South Korea in academic achievement is oversimplified. A new study out today by researchers at Stanford University and the Economic Policy Institute finds that comparisons of scores on international tests fail to adequately consider social and economic differences.

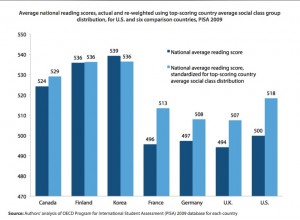

PISA scores for U.S. students increase when adjusted for social class. Source: What do international tests really show about U.S. student performance? (Click to enlarge).

“If the social class distribution of the United States were similar to that of top-scoring countries, the average test score gap between the United States and these top-scoring countries would be cut in half in reading and by one-third in mathematics,” write Stanford Education Professor Martin Carnoy and Richard Rothstein, a research associate at the Economic Policy Institute, in their report, What do International Tests Really Show About U.S. Student Performance?

The study also found big discrepancies in results for different tests. On the 2009 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), U.S. students scored 487 in mathematics while Finnish students scored 541. Two years later, on Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), U.S. students scored 509, just five points below Finland.

Carnoy and Rothstein also say it’s not true that low-income American students do significantly worse on the tests relative to their high-income classmates, while the economic achievement gap in other countries is much smaller. The U.S. has the smallest gap on reading and math on the PISA exam compared to France, Germany and England. And next to the top-scoring countries, the U.S. has a narrower achievement gap than Korea, and isn’t far behind Canada and Finland.

However, the authors do acknowledge that U.S. students score lower than students in the top-ranked countries across the board at every economic level. “At all points in the social class distribution, U.S. students perform worse, and in many cases substantially worse, than students in a group of top-scoring countries (Canada, Finland and Korea). Although controlling for social class distribution would narrow the difference in average scores between these countries and the United States, it would not eliminate it,” they write in the study.

On the 2009 PISA exam, which assesses 15-year-olds, the united States ranks 14th in reading and 17th in science, which are about average, but drops below average in mathematics to 25th. On TIMSS, which tests students in fourth, eighth and twelfth grades, U.S. students were above the international average in both science and mathematics in grade four, above the international average in science and below the international average in mathematics in eighth grade and among the lowest in both science and mathematics for twelfth grade students.

The message for policymakers is to take a more nuanced view of test scores, not to rely on just one exam, and not to jump to the conclusion that U.S. students are unprepared to compete in the global economy, said the researchers.

“Such conclusions are oversimplified, frequently exaggerated and misleading,” said Rothstein in a news release on the study.

Not so, says Andreas Schleicher, Deputy Director for Education and Special Advisor on Education Policy at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Scores on PISA adjusted by the number of books children report having in their homes. Source: What do international tests really show about U.S. student performance? (Click to enlarge).

Development, the group that administers PISA. He said the report “contains several fundamental misunderstandings and misinterpretations of the PISA data. In particular, the paper claims that there are flaws in PISA samples, which is simply incorrect and unsupported in the paper.”

The primary factor distinguishing students by social class, according Rothstein and Carnoy, is how many books a child has in his or her home. “Books in the home, to us, refers to the academic orientation of the household,” said Carnoy. He and Rothstein also say that this “indicator of household literacy” is used by both PISA and TIMSS and is “plausibly relevant to student academic performance.”

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.