Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

As the state looks to replace the California High School Exit Exam with a new version, or eliminate it altogether as a graduation requirement, it remains difficult to find much consensus among educators, researchers and advocates regarding the legacy of the test for California.

Gov. Brown last week signed legislation that exempted students from the graduating class of 2015 from having to take the test in response to a snafu that left thousands of seniors without the ability to take the test several more times as permitted under state law. Still to be resolved is the bigger issue of the fate of the test itself, which may be partly determined by assessing its impact since it became a graduation requirement nearly a decade ago.

The California High School Exit Exam (CAHSEE) debuted in 2001 as an effort aimed at ensuring every student graduated from high school with basic skills and, as the California Department of Education spelled out, “to identify students who are not developing skills that are essential for life after high school.”

Nearly 5 million students have taken the test since then. A majority of students passed on their first try, with an increasing number each year that the test has been administered.

Some, however, have struggled through multiple attempts before successfully completing it. About 249,000 students have failed the test since it became a graduation requirement in 2006.

Supporters of the exit exam say the exam has raised the bar for graduation by encouraging students to work harder and pressured schools to increase their efforts to close the achievement gap.

Photo by Tiffany Lew/EdSource

Certificate of Achievement awarded to Prospect High student Arlene Holmes instead of diploma because she didn’t pass the California High School Exit Exam.

Opponents argue that the test has discouraged some low-achieving students from staying in school and that it disproportionately punished low-income children and English learners who were unable to pass the test.

The research the state commissioned each year to evaluate the exit exam was generally positive about its impact, but other research reports were more critical. (For an overview of the research, see the end of this article.)

After an extended debate on the issue, Gov. Gray Davis signed legislation in 1999 to create the exit exam as a condition for students to receive a high school diploma. At the time, California joined a growing number of states that had such a requirement. By 2002, 24 states administered exit exams. Ten years later that number had grown to 26.

At the time he signed the law, Davis said the exam would add value to a diploma by ensuring students showed competency in math, reading and writing before they finished high school.

Students were tested on their aptitude in 10th-grade English and algebra, which students typically took between the 8th and 10th grade. Students could first take the test as sophomores, and if they didn’t pass, they could take it up to six more times before the end of their senior year. Even if they had not passed it by then, they could also take the exam up to three times in the year after their senior year and be awarded a diploma if they eventually passed.

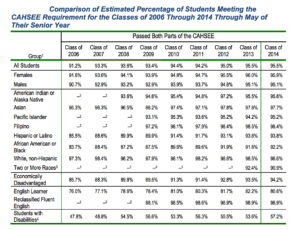

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO SEE A LARGER VIEW: This table shows the rate of students passing the California High School Exit Exam by the end of their senior year. Source: HumRRO

The test was first administered to freshman students in 2001, and they were required to pass it before they graduated in 2004. By 2002, only four in 10 students from the class of 2004 had passed the test, prompting lawmakers to postpone it as a graduation requirement another two years.

About 91 percent of students in the class of 2006 passed by the end of their senior year, including 67 percent who passed on their first try as sophomores. By 2014, about 95.5 percent of seniors passed, including 90 percent who passed on their first try as sophomores.

But given California’s size, even a small percentage of students failing the tests translates into large numbers of actual students. Last year, for example, 4.5 percent of high school students couldn’t pass the test by the end of their senior year. That amounts to nearly 20,000 seniors.

Former state Superintendent Jack O’Connell authored the legislation that created the exit exam when he was a state senator in 1999.

“I didn’t want a high school diploma to only reflect a certification of seat time,” O’Connell, who served as state superintendent from 2003 to 2011, said in a recent interview. “It should mean something much more. It should reflect the education we are delivering to our students.”

O’Connell, now a partner at Capitol Advisors Group, a Sacramento-based consulting firm, said the exam helped educators better target which students needed the most support by funneling them into intervention programs that helped improve their overall academic success.

“If you talk with folks in the field, this is one of the most significant reforms in high school they’ve seen,” he said.

The former state superintendent said results that show a higher rate of students from at-risk groups passing the test by 2014 compared to 2006 proves the exit exam accomplished one of its biggest goals.

“I didn’t want a high school diploma to only reflect a certification of seat time. It should mean something much more,” said former State Superintendent Jack O’Connell.

In 2006, about 86 percent of low-income students, 73 percent of English learners, 85 percent of Latino students and 84 percent of black students passed by the end of their senior year. By 2014, about 94 percent of low-income students, 82 percent of English learners, 94 percent of Latinos and 92 percent of black students passed.

“This exam helped close the achievement gap,” he said.

O’Connell said he now supports Senate Bill 172, which proposes to suspend the exit exam through 2017-18 to give the state time to decide whether a new test should be administered that is aligned with the Common Core standards.

“It was never intended to go on indefinitely,” he said. “Once Common Core came in, I knew it would be the end for an exam that’s based on California’s previous state standards.”

Critics have said there is little evidence the exam alone helped boost achievement of at-risk students. Some have said that other accountability systems implemented at the same time, including the federal No Child Left Behind Act and the state’s Academic Performance Index, contributed more to pressuring schools to improve achievement among all student groups. Instead, critics said, there is significant evidence the exit exam prevented many English learners, minority and low-income students from earning a high school diploma.

Arturo González, an attorney with the San Francisco law firm of Morrison & Foerster, filed a lawsuit in 2006 on behalf of a group of students from Richmond who sued the state in Valenzuela v. O’Connell, claiming poor and minority students were at a disadvantage because of sub-par teachers and resources in low-performing schools.

“This was a worthless exam,” González said. “The only thing it did was deny deserving students a diploma. In my view, it was more a political move by educators to show they were doing something.”

An Alameda County Superior Court judge in May of 2006 ruled that the exit exam could not be used to deny students a high school diploma, just three months after the lawsuit was filed. But the state Supreme Court reinstated the exam a few weeks later after the state appealed the lower court’s ruling.

González said the fact that the vast majority of students failing the exit exam are low-income, English learners, Latinos and blacks proves the assessment is flawed. Of the 19,679 students from the class of 2014 who did not pass by the end of their senior year, 68 percent were Latino, 49 percent were English learners and 77 percent were low-income, according to state Department of Education figures. (Some of these students fit into multiple categories.)

González said that if the state really wanted to improve achievement among at-risk students, it should have invested the millions of dollars it cost to create and implement the test on more AP courses, teacher training, after-school programs and tutoring in schools in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Students at many school districts across the state who met all other graduation requirements except for the exit exam have instead been awarded certificates of completion, a diploma-like document that looks like a high school diploma and states that the student met all of their individual district’s graduation requirements. But the document does not carry the same weight as an actual diploma when applying to college or for jobs. It is not known how many districts offer certificates of completion in lieu of a high school diploma because the state does not track those numbers.

Most four-year colleges, including the University of California and the California State University systems, decide whether to admit applicants with certificates of completion on a case-by-case basis. Students without diplomas in districts that chose not to award certificates of completion are often encouraged to enroll in community colleges, which don’t require diplomas, or work toward passing the General Educational Development test, or GED, a high school equivalency exam.

“I’ve had so many doors of opportunity slammed in my face for not having my diploma,” said Telesis Radford, who could not pass the exam before the end of her senior year.

Arlene Holmes received her certificate of completion in 2012 from Prospect High School in Pleasant Hill in Contra Costa County. Holmes easily passed the English portion, she said. But the math proved too difficult.

TIFFANY LEW/EDSOURCE TODAY

Arlene Holmes has been denied jobs and entrance into some training programs because she has not yet passed the CA High School Exit Exam.

“It is ridiculous how I actually worked extremely hard to even finish high school back in 2012,” she said.

Holmes, now 21, said not earning a diploma prevented her from enrolling in a vocational nursing program and other trade schools.

“I would have done a lot more with college and jobs because I am very capable,” she said. Holmes has received job offers, but was later told by human resource departments that they couldn’t hire her until she’s earned a diploma.

Telesis Radford received a certificate of completion from Santa Rosa High School in 2006 after failing the math section by just a few points.

“It was a sad and devastating day for me when I learned I wouldn’t receive my high school diploma,” Radford said. “I’ve had so many doors of opportunity slammed in my face for not having my diploma.”

Radford, now 27, was unable to enroll in a medical technician program, where she hoped to earn a phlebotomy license, which would allow her to work in a clinic or hospital drawing blood from patients.

“If I had my diploma, I would be in the medical field, and I would not be struggling like I am today to achieve and accomplish my dreams,” said Radford, who currently works as an administrative coordinator for the American Red Cross.

Lucinda Pueblos, assistant superintendent for K-12 performance and culture in Santa Ana Unified, said she has “mixed emotions” about the exit exam. Pueblos previously served as principal at Century High School, which also awarded certificates of completion.

While the exam overall set minimal expectations for students, it was still difficult for new English learners to pass the English section, she said. “It really did present a barrier for a lot of students.”

When the exit exam started, educators had to place a stronger focus on reading, writing and algebra in middle school in preparation for the test, said Pueblos, who also previously worked as a middle school principal. The pass rates improved, as students were better prepared.

She said the exam achieved its goal. “We were at least able to say they are at an 8th-grade level when they graduate,” she said.

Education Trust-West, an advocacy group for minority and low-income students, has generally supported the exit exam as another tool that helps increase the focus on struggling students.

“It prevented these students from being invisible,” said Carrie Hahnel, director of research and policy analysis at Education Trust-West. “It put responsibility and pressure on the system to help students.”

Hahnel said the yearly exam scores helped highlight the achievement gap for educators and policy makers. “The exam provided a lot of good data,” she said. “It also made the point that a high school diploma has to mean something, that you need these basic skills for college and careers.”

Human Resources Research Organization, or HumRRO, an independent evaluator, was commissioned by the state to review results of the exit exam each year since the program began. Its reports have generally been favorable, linking increased graduation rates and overall academic proficiency to the exit exam. The research group concluded in its most recent report in November 2014 that, “over fifteen years, we have seen test scores rise overall and for demographic groups defined by race/ethnicity and economic status. Graduation rates climbed, dropout rates declined, and successful participation in college entrance exams and Advanced Placement exams rose.”

HumRRO also reported that the exam has prompted schools across the state to create remedial opportunities for students who needed help passing it.

“Available evidence suggests that students have worked hard to meet the current (exit exam) requirement and that teachers have used class time to help them do so,” according to HumRRO’s latest report.

The report concluded that a higher rate of high school students are enrolling in advanced math courses, including geometry, intermediate algebra and calculus, as a result of the exit exam’s focus on algebra proficiency.

Still, HumRRO acknowledged that although scores for some minority groups, low-income students and English learners continue to improve, these students continue to lag significantly behind their peers.

A 2009 study by Stanford University professor Sean Reardon and UC Davis professor Michal Kurlaender concluded that the exit exam “has had no positive effects on students’ academic skills. Students subject to the (exam) requirement – particularly low-achieving students whom the exam might have motivated to work harder in school – learned no more between 10th and 11th grade than similar students in the previous cohort who were not subject to the requirement.”

The study compared 11th-grade scores on California Standards Tests, or CSTs, across years when the exit exam was a graduation requirement with years when it was not. On average, CST scores were slightly lower among students subject to the exit exam as a graduation requirement, according to the study. It also made the case that graduation rates of minority students who were struggling academically declined as a result of them failing the test – far more than the graduation rates of white students:

“The graduation rate for minority students in the bottom achievement quartile declined by 15 to 19 percentage points after the introduction of the exit exam requirement, while the graduation rate for similar white students declined by only 1 percentage point. The analyses further suggest that the disproportionate effects of the CAHSEE requirement on graduation rates are due to large racial and gender differences in CAHSEE passing rates among students with the same level of achievement.”

Reardon and Kurlaender said at the time that since the exam wasn’t working as it was intended, the state should consider eliminating it as a graduation requirement.

The Public Policy Institute of California released a study in 2008 that used the grades, test scores and behavior of 4th graders to reliably predict whether students would pass the exit exam. The study concluded the best way to ensure more students pass was to target intervention programs well before students begin high school. The study did not address the effectiveness of the exit exam.

Other studies over the years on exit exams nationally, including those from the Center on Education Policy and the Education Commission of the States, have also reported that the exams are most effective when states provide enough support to help struggling students eventually pass.

EdSource Today reporter Sarah Tully contributed to this report.

A grassroots campaign recalled two conservative members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Comments (16)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

sandra 9 years ago9 years ago

This makes me so upset. I walked stage participated in grad night and received a certificate of completion in 2007. i had good grades and if any had extra class credits but missed the math part of the cahsee by five points!!! I went back years after and still could not pass it. i just gave up all together. its not far at all. in college I don't qualify for financial aid because I do … Read More

This makes me so upset. I walked stage participated in grad night and received a certificate of completion in 2007. i had good grades and if any had extra class credits but missed the math part of the cahsee by five points!!! I went back years after and still could not pass it. i just gave up all together. its not far at all. in college I don’t qualify for financial aid because I do not have a diploma. so i paid all out of pocket for an education. Life got in the way had a child and basically worked with what i can find. in high school the teachers never ever did help the students out if they failed a part of the cashee. so it’s a fat lie when i read articles saying that the teachers/schools helped provide extra time or tutoring to those who have failed the cashee. where was my help when i needed it??? Oh top of that the material in the exam was briefly covered in school. Teachers never reviewed the material as thoroughly as it they should if it was going to be on a exam to determine weather a student or not would have received their diploma. It is ridiculous and unfair. I should recieve my diploma

magen adams 9 years ago9 years ago

So does this mean that the people that didn’t receive their diplomas can get it? I passed all my requirements for school but didn’t pass the exam?

Cathy Coleman 9 years ago9 years ago

It's a great thing that this CAHSEE Test will be done away with! I believe it was unfair exam! There moto was "No kids left behind" Liar!!! my daughter was left behind and not proper perpare. when she took CAHSEE 2006, at Rancho Cucamonga High School, she had all IP classes, attended summer school every year, she had more & above the number of credits to graduate from school, I her dad met with the … Read More

It’s a great thing that this CAHSEE Test will be done away with! I believe it was unfair exam! There moto was “No kids left behind” Liar!!! my daughter was left behind and not proper perpare. when she took CAHSEE 2006, at Rancho Cucamonga High School, she had all IP classes, attended summer school every year, she had more & above the number of credits to graduate from school, I her dad met with the counselor school principle we were given the run around business if you know what mean, their lack of actions was disappointing. The system has fail my daughter and many others have been held back from making having better life. It’s never acceptable let child fall throught the crack! they took an once in life time moment from my daughter who will never get back the opportunity to walk with her classmate to receive her diplomas. I thought this was so wrong & illegal how they treated us/my daughter, it’s been 9 years since this traumatizing experience. I believe a lawsuit should have been filed against school district. This needs to be rectify at the highest level. Please reach out to me and tell me how my daughter could file a petition to give her 2006 high school diploma. Thank you.

Sandra Thorpe Ed.D. 9 years ago9 years ago

We have in the last six years had to students who scored perfectly the first time. Last year all 10 th grade students passed both sections on their first try. I attribute this to trying harder to pass on the first try. During graduation ceremonies they are awarded $20.00 gift cards for each part passed ELA and math. Our school has 90 per cent low income families and we have a majority … Read More

We have in the last six years had to students who scored perfectly the first time. Last year all 10 th grade students passed both sections on their first try. I attribute this to trying harder to pass on the first try. During graduation ceremonies they are awarded $20.00 gift cards for each part passed ELA and math. Our school has 90 per cent low income families and we have a majority of Latinos. We need to stop making issues about race and income and start teaching and motivating students to learn .

Replies

Manuel 9 years ago9 years ago

“all 10th grade students passed both sections on their first try.”

That should not be hard to ensure when there were only 9 students enrolled in 2014-15 (7 in 2013-14, 12 in 2012-14, 14 in 2011-12). Or so says DataQuest.

Adult ED Student 9 years ago9 years ago

The recent passage of SB 725 grants exemption of the CAHSEE requirement for 12th grade high school student who have meet all their course requirements in 2015, this was passed because the State did not provide the CAHSEE test in July 2015. I have been inform that this exemption will not be avaiable for Adult school students and only applies to high school students, which was told to … Read More

The recent passage of SB 725 grants exemption of the CAHSEE requirement for 12th grade high school student who have meet all their course requirements in 2015, this was passed because the State did not provide the CAHSEE test in July 2015. I have been inform that this exemption will not be avaiable for Adult school students and only applies to high school students, which was told to me by an Adult school and Ca Cahsee dept. The issue that I see is it is discrimination against Adult Ed high school students, since both regular high school student and Adult Ed high school students are required to pass CAHSEE for the same Diploma. The test was unavailable to both groups in July 2015 and will continue to be unavailable for the posted Oct 2015 test date.

The 14th Amendment and the CA Declarations of Rights grants equal protection.

CA Constitution article 1 sec 7 , 2b reads(b) A citizen or class of citizens may not be granted privileges or immunities not granted on the same terms to all citizens.

Accordingly SB 725 grants a privllege to 2015 High School student which it denies to 2015 Adult Ed high school students.

HELP

The legistature has SB 172 ( suspending the CAHSEE Test) it is in process, but I have been told that it may not make it out in time, If it were to pass, it would still leave Adult Ed student in limbo till Jan 2016 to get a high school diploma. Nevertheless I urge you to call your legislators to urge a quick passing of SB172 this year, to help ALL Students who are being deprived of an equal exemption under SB725, which was a result of the State of California DEPT of Education’s FAILURE to provide the required testing.

Parent 9 years ago9 years ago

I would actually rather hear from freshman college professors of 4 year and junior colleges about what their opinions are on indicators of “college readiness”.

zane de arakal 9 years ago9 years ago

Useless for improving instruction. I am a retired school district super of the 1960’s ITBS era, it served us well in modifying instruction at all levels. School business in California in those days wasn’t concerned for identifying an exit score for masses of 12th graders.

Manuel 9 years ago9 years ago

Does the CAHSEE score received by a student demonstrates that s/he has the academic preparation required to graduate from high school? While all my children did pass this test and have been successful in college, I have my doubts based on one single point of evidence: an LAUSD valedictorian could not pass the CAHSEE. The name of this student has been shrouded in secrecy, but I was told by a person that knew the particulars of … Read More

Does the CAHSEE score received by a student demonstrates that s/he has the academic preparation required to graduate from high school?

While all my children did pass this test and have been successful in college, I have my doubts based on one single point of evidence: an LAUSD valedictorian could not pass the CAHSEE.

The name of this student has been shrouded in secrecy, but I was told by a person that knew the particulars of this case that it truly did happen.

Let me tell you the story (which I’ve told before, but it is worth re-telling):

On January 13, 2010, Judy Elliott, Ph.D., Chief Educational Officer at LAUSD sent out a memo inviting a select group of teachers, staff and community members to participate as members of a “Marking Practices and Procedures Task Force.” According to the memo, “academic grades are supposed to reflect a student’s level of success in mastering grade-level standards in all subject areas at each grade level. An LAUSD analysis of California Standards Test (CST) and grades assigned in grades 8, 9, and 10 English and mathematics courses revealed cases where grades did not correlate with the student’s CST results.”

Because of this, Dr. Elliott decided that there was a need to revise how classroom grades were assigned. The task force was asked “to identify any challenging issues regarding the discrepancies between CST and classroom grades and why they might be occurring. We will review current marking practices and procedures and make recommendations as appropriate, for improving and aligning student performance and standards-based success.”

I was present at the first meeting of the task force and Dr. Elliott told us that the entire exercise had been precipitated by a request from Superintendent Cortines to find out how it was possible that a valedictorian could not pass the CAHSEE. As you surely know, no one can graduate from high school without a passing score in the CAHSEE, much less appear at the graduation’s stage as a valedictorian. Naturally, this caused the parents to intercede for their child and took their complaint all the way to Superintendent Cortines. I have no idea what the result of that petition was because we were not told. But Dr. Elliott did tell us that she was asked by the Superintendent to get to the bottom of it. (She, of course, never put this tale in writing. The woman is no fool! She has a Ph.D. in education, you know!)

Reasoning that CAHSEE scores should be reflected on the relationship between classroom grades and CST scores, she commissioned a simple study of that relationship. After examination of plots of the 2007-08 and 2008-09 scores of students against their classroom marks, Dr. Elliott conclude that there was simultaneous grade inflation and deflation across LAUSD. How else could it be explained that, for example, 43% of 8th graders getting “A” in English at LAUSD middle schools were not proficient while 39% of those getting “A” in math were also not proficient? In addition, 40% of 8th graders getting “F” in English were “proficient or above” while only 22% “F” students were also “proficient or above” in English. It boggles the mind because it is against common sense, doesn’t it?

Hence, LAUSD had to take a hard look at how grades are being granted across the 100 middle schools and 80 high schools because, again, everybody knows that the CST scores should reflect the student’s classroom mark.

In the end, not much came from this task force. What did come out was a “homework” policy to increase the likelihood that there would be a paper-trail that could lead to understand how a student could get an “A” and still not be proficient in the CSTs which surely meant that the student could not pass the CAHSEE. I’ll leave you to ponder on who was going to be left holding the bag under this scenario.

Unfortunately, the homework policy blew up on Ms. Elliott’s face. John Deasy, the new Superintendent, asked her to look for better opportunities elsewhere. He had just installed Jaime Aquino, Ed.D., as her supervisor so the time was ripe for that.

Yes, it sounds like a Homeric tale: a single student, a valedictorian no less, can’t pass the CAHSEE and as a result LAUSD determines that there is grade inflation and deflation simultaneously because the grades don’t correlate with CST scores across the entire district (we are talking about 300,000+ students here). Something must be done but nothing happens because the interest of the new Superintendent is elsewhere (it was VAM, but that’s a story for another time).

The true moral of the story is that it cannot be guaranteed in a district with 10% of the state’s students that a student’s academic achievement in the classroom will be reflected on the results of the CSTs or the CAHSEE, their cousin once removed.

And this is not just based on the fate of a single person who happens to be a valedictorian. It is reflected on the fact that the 2008-09 scores of 5th graders presented the same percentage distribution whether the kid was getting a “4” or a “1”. And in both English and math. Something that repeats for every “A” student in middle and high school. How is that possible if the grades should be correlated with scores? (If someone is interested, I got copies of all the original documents.)

That’s why I agree with the words from the retired ETS vice president as quoted in the LA Times when talking about another test, the ACT: “A test score is a probability statement. The whole apparatus is an artifice designed to get kids from high school to Harvard.”

In the case of the CAHSEE, it is test designed to convince California that the kid learned something in high school. But it is really a probability statement, which is no better than a coin flip. You win half the time, half the time you lose.

(One last thing: I have come across people who would admit, sotto voce, that their otherwise good student child can’t get through a standardized test. I guess this is equivalent to admitting to have a crazy aunt living in the attic.)

Don 9 years ago9 years ago

If the CAHSEE functioned to foster more rigor that might be one reason to reinstate it. But since it is a low bar for rigor to begin with, the two ideas don't really make sense. In the real world, what opportunities does a high school diploma offer? Mostly low level ones. So why do we as a society need to make sure our high school graduates are qualified to do low level work? Employers, community … Read More

If the CAHSEE functioned to foster more rigor that might be one reason to reinstate it. But since it is a low bar for rigor to begin with, the two ideas don’t really make sense. In the real world, what opportunities does a high school diploma offer? Mostly low level ones. So why do we as a society need to make sure our high school graduates are qualified to do low level work? Employers, community colleges and trade schools can make those determinations on an individual basis. We don’t have an exam for the major in order to graduate from a 4 year college bachelor’s program where students, upon exit, are likely to have more responsibility entering the work force.

Replies

sustu 9 years ago9 years ago

In the late 1980’s there used to be a test of basic writing skills that students had to pass in order to earn a B.A. or B.S. at CSULA, and I thought at other Universities as well. Students had to write an essay or two. I guess that test is no longer in place?

Frances O'Neill Zimmerman 9 years ago9 years ago

Thanks for this excellent article which is so informative and broadly illustrative of our divisive educational cross-currents. I was struck by arguments for getting rid of the CAHSEE (or devising a timely replacement version) because some low-achieving socio-economically impoverished students cannot pass it and thus are prevented from receiving a full high school diploma and thus are prevented from getting desirable jobs. Does this description say dump the exam? Or does it say provide better instruction … Read More

Thanks for this excellent article which is so informative and broadly illustrative of our divisive educational cross-currents.

I was struck by arguments for getting rid of the CAHSEE (or devising a timely replacement version) because some low-achieving socio-economically impoverished students cannot pass it and thus are prevented from receiving a full high school diploma and thus are prevented from getting desirable jobs. Does this description say dump the exam? Or does it say provide better instruction and encouragement for those bottom-tier students to assure they can do the work, accomplish the task and pass a milestone toward a high school diploma? If we cannot update something as simple and straightforward as the eighth grade-level CAHSEE and commit to its value, why do we have any standards or graduation requirements at all?

Jim Mordecai 9 years ago9 years ago

My understanding is that most accurate predictor of college readiness is firstly a student grades, not standardized tests. And, graduation requirement has always been maintaining a minimum grade point average; as well as a minimum standard of attendance. If these three things are true, then Jack O'Connell's term "seat time" is inadequate because it doesn't capture these other factors that were associated with graduation prior to an exit examine. This article mentioned examples of … Read More

My understanding is that most accurate predictor of college readiness is firstly a student grades, not standardized tests. And, graduation requirement has always been maintaining a minimum grade point average; as well as a minimum standard of attendance.

If these three things are true, then Jack O’Connell’s term “seat time” is inadequate because it doesn’t capture these other factors that were associated with graduation prior to an exit examine.

This article mentioned examples of the exit examination being a barrier to students getting additional education. If that is true of one student, instead of thousands reported in the article, then I would still be 100% against reinstating the exit example and dropping a test standard that unnecessarily becomes a barrier to students seeking additional education. Performance in the classroom should be valued more than performance on a test.

Gary Ravani 9 years ago9 years ago

As noted by another commentator below I know of NO cases where students were awarded a diploma for "seat time," that is just sitting in class and not participating in the assignments, quizzes tests, homework etc. This is little more than an urban myth, and pushed by those who have spent little to no time in an actual classroom. I do know of students who were denied access to a fully rounded curriculum, including electives where … Read More

As noted by another commentator below I know of NO cases where students were awarded a diploma for “seat time,” that is just sitting in class and not participating in the assignments, quizzes tests, homework etc. This is little more than an urban myth, and pushed by those who have spent little to no time in an actual classroom.

I do know of students who were denied access to a fully rounded curriculum, including electives where they might find inspiration to stay in school, because they were doubled up in extra class in ELA and math because of the CAHSEE requirement and because state tests were focused on those two content areas.

el 9 years ago9 years ago

I just don't know what I think about this exam. I am so sympathetic to the students who wrote heartfelt (if also telling) comments about not being able to pass the exam and how that has limited their opportunities. I also - and this may be my character flaw - don't fully understand why this test is such a barrier and am not wholly convinced that it is the only barrier. As a community member, I … Read More

I just don’t know what I think about this exam.

I am so sympathetic to the students who wrote heartfelt (if also telling) comments about not being able to pass the exam and how that has limited their opportunities. I also – and this may be my character flaw – don’t fully understand why this test is such a barrier and am not wholly convinced that it is the only barrier. As a community member, I have seen very many students pass it on the first try. I am not sure that the issues are internal to the student; and if that’s so, it hurts to have the hammer fall on students, especially when they express motivation and effort.

Colleges and others *could* choose to accept the certificate of completion. They choose not to. Withdrawing the exit exam deprives them of a choice there, but presumably those colleges have made a deliberate and thoughtful choice. I’m interested to hear from some of those institutions what they think.

I don’t understand exactly the situation of special ed kids and where the line is there. This perhaps is the most persuasive argument that I’ve heard, that kids who are lower functioning and cannot pass the exam are getting full diplomas, and yet we apparently have young adults who have taken the exam, 6, 8 times and can’t pass it? It would be one thing if the student took it a couple of times and just didn’t put in effort to do well. It seems to me that a student who has made so many honest and frankly inconvenient attempts and is still not successful is probably someone who should have had an IEP.

Doug McRae 9 years ago9 years ago

Thanks to EdSource and Fermin for a very balanced treatment of the issues surrounding CA's HS exit exam. The issues are quite similar to HS exit exam discussions in other states. The primary drivers for CAHSEE back in 1999, as I recall, were reports of students with very little if any documentation of basic skills achievement, rather only attendance or seat time, receiving HS diplomas. The thought that CAHSEE could change instruction at the high schools … Read More

Thanks to EdSource and Fermin for a very balanced treatment of the issues surrounding CA’s HS exit exam. The issues are quite similar to HS exit exam discussions in other states.

The primary drivers for CAHSEE back in 1999, as I recall, were reports of students with very little if any documentation of basic skills achievement, rather only attendance or seat time, receiving HS diplomas. The thought that CAHSEE could change instruction at the high schools in CA was very secondary.

About 2 years after the CAHSEE statute was approved, the Co-Chair of the CAHSEE advisory committee [Supt, Glendale Unified, I believe] was asked a Q at a State Board meeting on the impact of CA’s 1997 standards on instruction in his district. His off-the-cuff answer was — a good deal of movement toward standards-based instruction at the elementary grades, some signs of progress at the middle school grades, and (well) at the high school grades it was like “trying to move a cemetery.” When CAHSEE turned fully operational in 2006, it had moved a number of tombstones for the instruction of basic academic skills needed for a high school diploma in California.

There are, of course, contending and contrasting opinions on the worth of CAHSEE over the past 10 to 15 years. These opinions and positions deserve a full legislative hearing before a HS exit exam program is continued or allowed to expire. SB 172 (Liu) suspends CAHSEE while theoretically that decision is studied — a suspension biases that study and decision, and is particularly poor policy if indeed an exit exam program is continued by the legislature. Oh, and it puts the recommendation for continuation or expiration solely in the hands of current SSPI Torlakson, sponsor for SB 172, with an advisory group he gets to appoint. Anyone wanna guess what that recommendation might be, coming from a source who has already clearly tipped his hand by prematurely canceling the July administration of CAHSEE despite current statute and an approved test administration budget for 2015-16?