Compared with their peers in developed nations, American 15-year olds are slightly above average problem solvers, but not as good as students from Asian nations who regularly shellac them in math, reading and science tests, according to the results of a new international assessment released today.

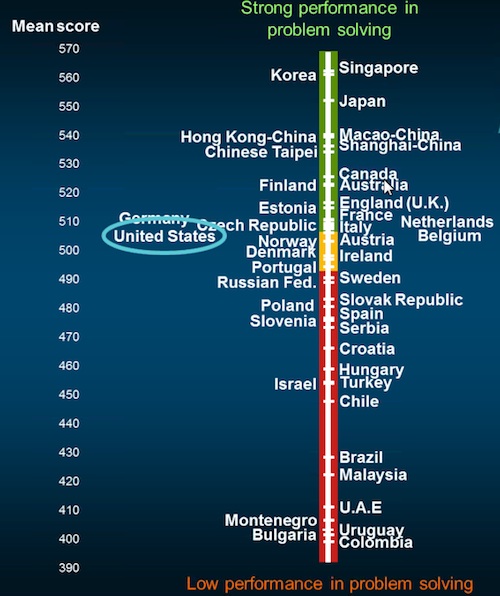

Scores from the first-time problem-solving exam of PISA, the Programme for International Student Assessment, put them on par with students from Germany, Italy, France and the Netherlands but behind those from England, Finland, Australia, Canada. At the head of the pack are Singapore, Korea, Japan, and Shanghai-China. The computer-based test was given to 85,000 students from 44 nations in 2012, including 1,273 students in 162 schools in the United States. Forty-four nations administered the test, including 28 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a global policy forum that runs PISA. The average score for those nations was 500, 8 points below the United States. Singapore, with 562, registered the highest and Colombia, with a score of 399, the lowest. (Neither is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.)

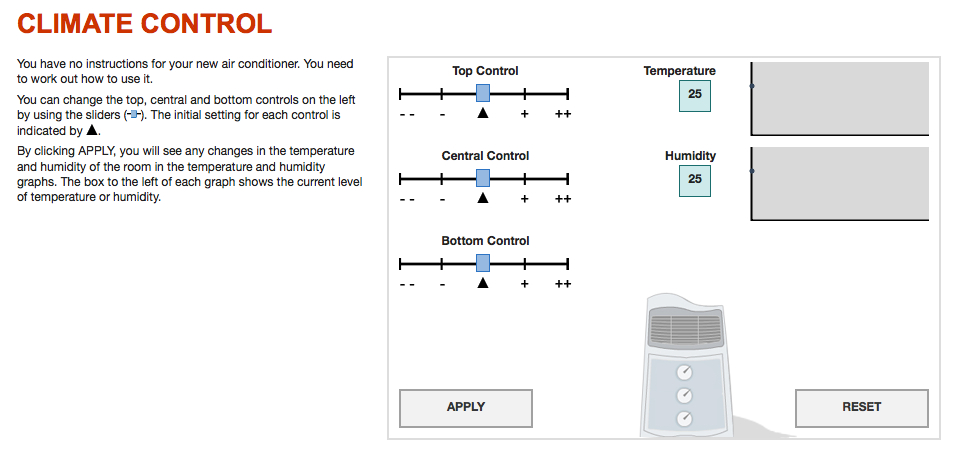

This sample PISA problem-solving question asks students to figure out how to work climate controls of an air conditioner that comes without instructions. Source: PISA

The new assessment purports to measure the reasoning, creativity, ingenuity and cognitive skills needed to solve everyday, practical problems whose solutions aren’t readily apparent. The test questions didn’t require specific content knowledge in math or science; they required logic and analytic skills to figure out a seating chart at a birthday party, based on a number of conditions – who could or couldn’t sit next to whom – or to figure out how to work a new air conditioner’s controls without instructions (click here to solve that problem). Nonetheless, PISA’s report said there generally was a correlation between how well students did in PISA’s math and science tests and the problem-solving test.

PISA reported U.S. students’ scores were higher than what would have been predicted, based on their PISA math scores. David Plank, executive director of Policy Analysis for California Education, said U.S. students have been “beaten up for decades” in international tests like PISA, so he found this result interesting and encouraging. In the 2012 PISA math assessment, U.S. 15-year-olds fell below the OECD average by 13 points (481 to 494) and their scores were lower than 29 of the 65 nations or provinces that took the test and about equal to nine.

American students are demonstrating creativity and analytical skills to apply what they learn, Plank said, The Common Core standards, which California and 44 other states have adopted, will reinforce those qualities, with an emphasis on critical thinking and understanding underlying math concepts, he said. “We’re moving in the direction that prizes those skills more highly than a mastery of algorithms,” he said.

PISA analyst Pablo Zoido said it’s not possible to directly link a nation’s specific policy and PISA results. But, he added, “That said, the Common Core is a step forward in the direction of what is already being done in top-performing countries.”

Nations’ and provinces that took the test are shown from high to low scores, with the orange clot in the middle, including the United States, about average or slightly above. Source: PISA.

Those countries include Singapore, which PISA highlighted in its report on the problem-solving assessment. Singapore undertook a review five years ago that “identified the 21st century competencies considered important: critical and inventive thinking; communication, collaboration and information skills; and civic literacy, global awareness and cross-cultural skills.” A national framework now guides the development of a national curriculum and school-based programs “to nurture these competencies,” the report said.

In a summary of U.S. results, PISA said that:

- U.S. students perform best on interactive tasks, which require students to uncover some of the information needed to solve

problems. This suggests that U.S. students “are open to novelty, tolerate doubt and uncertainty, and dare to use intuition to initiate a solution.”

- While boys perform better on average across the OECD, in the United States boys and girls scored about equally.

PISA analysts concluded that in nations where students scored the highest in problem solving, “students not only learn the required curriculum, they also learn how to turn real-life problems into learning opportunities.” Furthermore, “teachers and schools can foster students’ ability to confront – and solve – the kinds of problems that are encountered almost daily in 21st century life.”

American critics of past PISA tests have said that flaws in methodology and significant demographic and cultural differences among test takers cast doubt on PISA’s national rankings and the validity of comparisons of nations’ curriculums and approaches to education. Last year, Tom Loveless, a senior researcher at the Brooking Institution in Washington, dismissed Shanghai-China’s top scores in the 2012 math, science and reading tests, because Shanghai’s elite system excludes millions of migrant children. On Monday, he questioned whether it is even useful to try to measure “generic problem-solving skills” devoid of the actual application of science or mathematical knowledge. “Math literacy is needed to solve real world problems applying math,” he said in an interview. “No country should take this test seriously.”

And Frederick Hess, resident scholar and director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, wrote in an email, “It’s a very healthy thing to seek valid, reliable assessments that stretch our measures of K-12 learning beyond reading and math. That said, I think even PISA’s more conventional results ought to be taken with a big grain of salt. Here, I think scores should be taken with a whole shaker.” He said he shared concerns over PISA’s nation-to-nation comparisons, and, in the latest assessment, “there are good questions about just what these questions gauge – and whether they provide a good or useful measure of student learning or school performance.”

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments (1)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

Hannah Katz 10 years ago10 years ago

Interesting, but it would help if you would list countries like Mexico and Nigeria. It would be interesting to compare Mexican students to Mexican American student results. Same with African American students and students from various African countries. U.S. educators may actually be outperforming their foreign competitors.